© Denzil Green

Mincemeat is a mixture of dried and candied fruit, raisins, currants, sugar, suet, apples, brandy, spices, and nuts. Many variations are possible and available, including vegetarian versions, alcohol-free versions that use North American soft apple cider, and nut-free.

It is used as a filling for pies and tarts, especially at Christmas time. It is a British tradition that transferred to all the new English-speaking countries born out of British colonies, such as America, Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

You can buy mincemeat already made in jars or tins. Harrods alone sells over 10,000 pounds (4,000 kilos) of jarred mincemeat each December (as of 2004).

The traditional traditional time to mix up one’s mincemeat for the coming Christmas festivities was Stir-Up Sunday.

Mincemeat Pies / Tarts (aka Wayfarers Pies)

In the United Kingdom, mincemeat pies are often referred to as just “mince pies.” Out of context, that could of course mean “minced beef” pies, but at Christmas everyone knows what it means. And, even though “mincemeat pies” could in theory be used to refer to whole, large pies that have several servings in them, in practice it actually means “mincemeat tarts” as they are far more common than one whole, large pie.

In Canada and the US, small tart-sized mincemeat pies will be called “mincemeat tarts.”

Elizabeth Craig’s mincemeat

Elizabeth Craig gave this mincemeat recipe in the 1920s:

“Old Mincemeat Recipe. If you prefer mincemeat made with meat as well as fruit, try this recipe, which was once used by a famous tavernkeeper: Boil till tender, then chop finely, a calf’s foot and a pickled ox tongue, mix in a basin with one pound washed and dried currants, one pound stoned and lightly chopped raisins, one and one-fourth pounds tart apples, peeled and chopped, one-half pound finely shredded suet, one-fourth pound sugar, three ounces each of candied citron, lemon and orange peel, finely minced, the grated rind of half a lemon and the strained juice of two lemons, a small teaspoon of mixed spice and a tiny pinch of salt. Moisten mixture with one and one-half pints of cider if one-half pint sherry and a pint of brandy are not available.

Fruit Mincemeat. Very few English housewives put meat in their mincemeat now. The following recipe for fruit mincemeat is more popular: Peel, core and chop two pounds tart apples finely, mix in a basin with one pound stoned and chopped raisins, one pound washed and dried currants, three ounces each of candied lemon and orange peel and two ounces citron peel, all finely minced, and a nutmeg grated. Stir in one pound sugar, the granted rind and strained juice of a lemon, three-quarters pound finely minced suet, a saltspoon of salt, one-fourth pound chopped glace cherries and two wine glasses of brandy or homemade wine.

Whichever recipe you choose, mix the ingredients well together before packing it into a jar and sealing cover down. It is improved by being made a few days before it is required, when made into pies with rough puff pastry.” [1]Elizabeth Craig. “Boar’s Head and Rough Puff Pastry In an Old-Time English Feast.” Reprinted in: Syracuse Herald, New York State. 4 January 1925, Home Institute Page.

History Notes

Mincemeat was first born in Elizabethan times. Medieval cooking and tastes still lingered, with blurry lines between savoury and sweet. In a meat pie, you might put lots of fruit.

Mince pies were banned when the Puritans under Oliver Cromwell came into control of Parliament (roughly from the late 1640s to the late 1650s.) The Puritans were already predisposed to ban anything in the way of pleasure and self-indulgence, but what pushed them over the edge about mince pies is that they were traditionally made in the shape of a cradle, representing the manger. To the Puritans, this was another Popish representation.

John Timbs, a Victorian writer, wrote:

“The minced pie was treated by the Puritans as a superstitious observance and after the Restoration it almost served as a test for religious opinions. According to the old rule, the case or crust of a minced pie should be oblong, in imitation of the cradle or manger wherein the Saviour was laid; the ingredients of the mince being said to refer to the offerings of the Wise Men.” [2]John Timbs. Banbury Cakes and Banbury Cross. In: S. Lucas, Ed. Once a Week: An Illustrated Miscellany of Literature, Art, Science. London: Bradbury and Evans. Volume 8. December 1862 to June 1883. Page 584.

When mince pies were legal again, they came back in a round form.

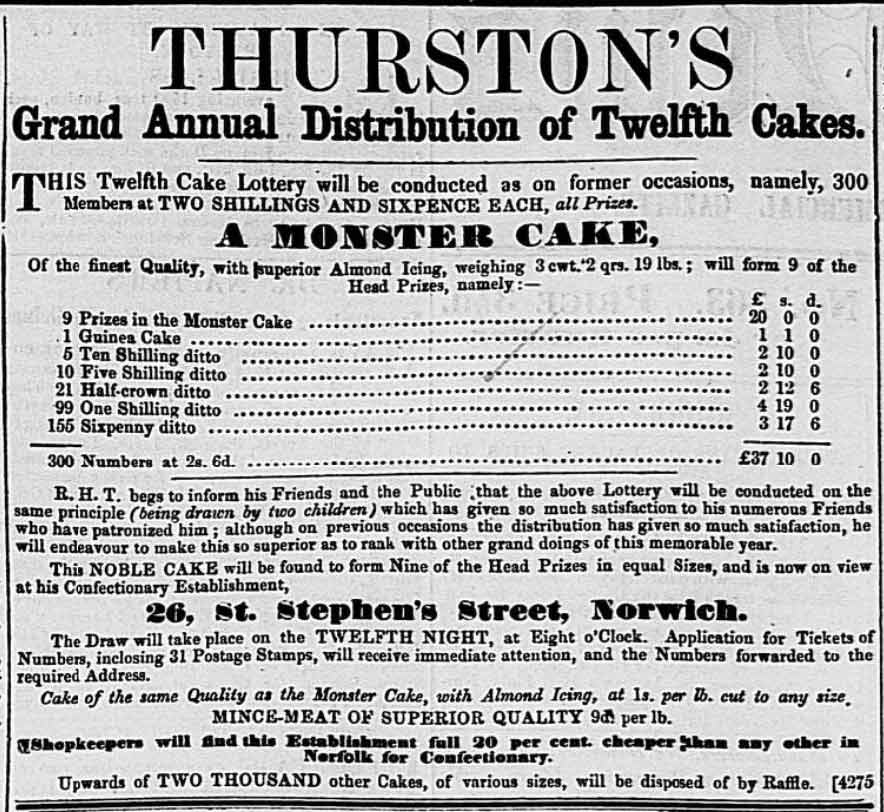

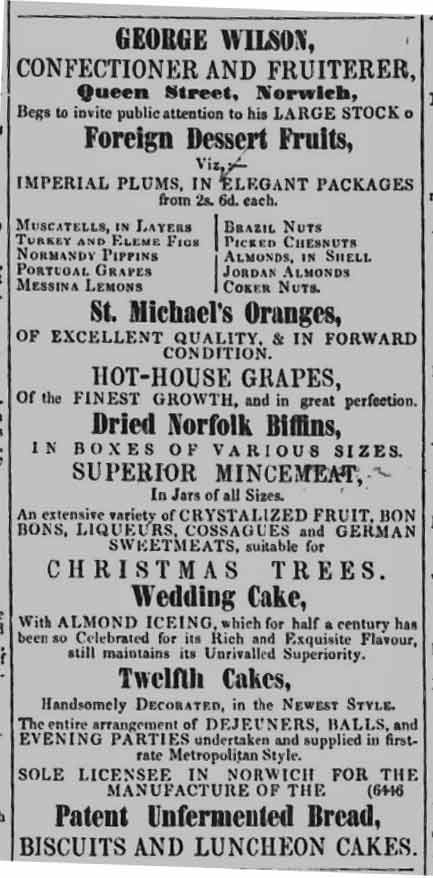

By the early 1850s, commercially-prepared mincemeat starts to appear for sale both in bulk and in jars.

Ad for commercially-prepared mincemeat sold by the pound. A competitor, Wolton And Co. at 47 London Street, Norwich, also offered prepared mincemeat at 1s. per pound. In: Norwich, Norfolk, England: Norfolk News: Saturday, 20 December 1851. Page 2, col. 2.

George Wilson (confectioner and fruiterer, Queen Street, Norwich) advertisement for mincemeat in jars of various sizes. In: Norwich, Norfolk, England: Norwich Mercury. Saturday, 20 December 1851. Page 1, col. 3.

In the United States, the Heinz company started selling prepared mincemeat in the 1877. It was available in wooden buckets, stone crocks or in Heinz’s revolutionary idea of glass jars, allowing purchasers to inspect the contents.

“Many recipes of the time called for rum, but Heinz used cider vinegar. Heinz also added candied citron to the recipe… A published Heinz recipe called for ‘fresh meat selected from the country’s best output; rich, white suet; large, juicy, faultless apples; Four-Crown Valencia confection raisins, carefully seeded; plump Grecian currants of exceptional flavor, each one thoroughly cleansed and purified; rich candied citron, orange and lemon peels.” [3]Skrabec, Quentin R. H.J. Heinz: A Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009. pp 73 – 74.

Note the business acumen in the use of ingredients such as “carefully seeded” Valencia raisins, and Grecian currants, with which the average housewife’s recipe couldn’t hope to compete. It also reminds the housewife that she will be spared the labour of having to manually seed each raisin one by one.

Up until the late 1800s, the recipe still contained minced beef. Mrs Beeton’s recipes for mincemeat do.

Nowadays, the beef suet is the last trace of meat in mincemeat.

Literature & Lore

In 1662, Samuel Pepys records in his diary that on Christmas Day he ate mince pies that he bought (he notes that he had to buy them as his wife was ill.)

One Christmas superstition is that for every mincemeat pie you eat between Christmas and Twelfth Night (the evening of the twelfth day after Christmas), you will have one month of happiness in the coming year. Actually, the full superstition was that you had to eat 1 pie a day at 12 different houses.

In an 1869 newspaper homily, this “luck” tradition is mentioned, along with an accounting of desirable ingredients in the mix:

“Let charity be like mincemeat, abundant, of all kinds of wondrous simple compounds, meat for substance, apple for juiciness, suet for richness, plums and currants for fullness, sugar in plenty for sweetness, salt for savour, wine and brandy for strength and keeping, and lemon, citron and candied peel and spice for flavour and raciness — well-proportioned, prepared beforehand, long kept, bounteously served out in due time, and in the plainest, cleanest old-fashioned tin dishes. The saying goes, ‘as many mince pies as you can eat between Christmas and New Year, so many happy days will you have in the year.’ Mr Editor, may you and your readers have such mincemeat, physically and spiritually, as I have described, and happy days will follow such Advent Thoughts and Doings.” — M.A. Advent Thoughts for Newspapers: When and How to Make Mincemeat. To the Editor. Norwich, Norfolk, England: Norwich Mercury. Saturday, 18 December 1869. Page 5, col. 3.

The luck superstition tradition was still alive at the start of the 1900s:

“A Yorkshire Wife’ writing from Beverley to the ‘Daily Mail’ (London) says: ‘Every mince pie eaten between ‘Stir-up Sunday’ and Christmas Day means a happy month in the New Year. But the pies must be provided by other people and only one from each house counts.’ ‘Stir-up Sunday’ is the 25th Sunday after Trinity; this year it fell on November 25th.” — Hull, Yorkshire: Hull Daily Mail. Thursday, 27 December 1900. Page 2, col. 5.

An 1882 household column notes that the traditional time to mix up mincemeat is Stir-Up Sunday, and gives two recipe options: one with beef suet, and the other with beef suet plus actual beef:

“‘Stir up Sunday’, as the last Sunday in the Church year is called — the collect for the day commencing with the words ‘Stir up’ — as a reminder to many people that the time has come to prepare for Christmas, by laying in a stock of mincemeat. That day was the Sunday before last; and we dare say that the mincemeat has already been prepared in many households. Should any of our readers require a recipe, however, here are two:

No. 1. — Mincemeat should be made three or four weeks before using, as it greatly improves by keeping. Two lbs. of apples, pared and chopped; three-quarters lb. of beef suet, neatly cleaned and chopped small; half lb. raisins, half lb. Sultana raisins, both stoned and chopped; juice and rind of one lemon, chopped; one tablespoonful cinnamon (if approved), two lbs. sugar, two teaspoonsful salt; half a pint brandy, one glass sherry, to be added two days after the other ingredients have been mixed. Mix thoroughly, and put in a jar; cover, and keep in a cool place.

No. 2. — Half a lb. of beef and 2 lbs. of suet, chopped fine; one and a quarter lb. raisins, stoned and chopped; one and a quarter lbs. currants; one lb. weight of apples after they are pared, one and a half ounces cinnamon; eight of an oz. mace; three-eighths of an oz. nutmeg; three-quarter lb. of sugar, a pinch of salt; juice and peel of one lemon, a little brandy and sherry to be added afterwards.” — The Household: Mincemeat. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland, England: The Newcastle Courant. Friday, 8 December 1882. Page 7, col. 5.

A Nice Mince Pie: or The Merry Maids of Middlesex

An 1867 short story, “A Nice Mince Pie“, contains a discussion of the various ingredients that people of the period would use in their versions of mincemeat:

‘But dis mince pie, madesmoiselles, about which you make so much talk? Mince pie — what is dat?’ the fair Petitose, greatly puzzled, inquired.

‘Don’t you know?’ little Laura exclaimed in astonishment. ‘Why mince pie is apples, and beef, and currants (what you call ‘raisins de Corinthe’) and suet, and salt, and sugar, and almonds and — and — ‘

‘Dat must be veree nastee!’ interrupted the Petitose, with a visible shudder running through her pretty frame.

‘Don’t forget the brandy, dear’, Norah gravely added; ‘nor yet the Malaga raisins, nor the candied citron, nor the grated nutmeg — ‘

‘But all dat mixture shall be ver-ree nastee indeed’, pertinaciously objected Mademoiselle.

‘Oh no, it isn’t’, Goody explained. ‘On the contrary, it’s very nice; especially if you make it before Stir-up Sunday, and stir it up well every Sunday afterwards.’

‘Aunt Mary, however’, Laura said, ‘uses tongue instead of beef; and she also puts in ground ginger, and cloves, and bruised coriander seed.’

‘And grandma flavours with pineapple run, Madeira wine, and orangeflower water’, chimed Miss Stephens, forgetting her griefs in the increasing interest of the mince-pie formula.

‘As if her grandmother could possibly be alive’, Miss Touchwood slyly whispered to Goody, ‘unless she has survived to be a hundred and fifty! Ask her what her great-great-grandma flavours with.’

‘Miss Pinshaw’s mince pies for the charity children’, said Norah in a subdued tone of voice, as if communicating some important secret, ‘have carrots, and lemon juice, and common grocers’ plums, and orange peel, and all-spice, and beef dripping, and bread crumbs, and treacle, and chopped liver, and ginger wine for economy’s sake, instead of the more expensive articles; and really the children enjoy them so much.’

‘Poor things! Ignorance is bliss’, the lively Emma ejaculated. ‘But you have forgotten the essential and indispensable crust, which is to hold together the various ingredients together. Norah, with her usual cleverness, would set about making pies without pie-crust; but there are things which cannot be dispensed with.” — A nice mince pie: or the merry maids of Middlesex. Dorchester, Dorset, England: Dorset County Express and Agricultural Gazette. Tuesday, 24 December 1867. Page 3, col. 1.

Full story: A Nice Mince Pie; Or, The Merry Maids of Middlesex (1867) A social comedy short story centering on mincemeat pies.

Sources

Baldini, Luisa. Centuries old mince pie recipe found. BBC News. 13 December 2004.

References

| ↑1 | Elizabeth Craig. “Boar’s Head and Rough Puff Pastry In an Old-Time English Feast.” Reprinted in: Syracuse Herald, New York State. 4 January 1925, Home Institute Page. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Timbs. Banbury Cakes and Banbury Cross. In: S. Lucas, Ed. Once a Week: An Illustrated Miscellany of Literature, Art, Science. London: Bradbury and Evans. Volume 8. December 1862 to June 1883. Page 584. |

| ↑3 | Skrabec, Quentin R. H.J. Heinz: A Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009. pp 73 – 74. |