National flour recreation. © CooksInfo / 2021

National flour was a flour developed in the United Kingdom to help imported wheat go further, while also appeasing consumers by being a compromise between white and whole wheat flour, and appeasing nutritionists as well who were charged with keeping the UK’s population “fighting fit”.

Though ratios were adjusted over the years, the starting composition of the was 85% sieved “whole wheat” and 15% white. It was made for a total of 14 years.

Note that the famous, and expensive bread, Pain Poilâne, which is still made in Paris today, also uses a similar flour.

See also: National Loaf, British Wartime Food

- 1 Cooking with National Flour

- 2 Recreating National Flour

- 3 The political purpose of National Flour

- 4 Primary use of National Flour

- 5 Composition of National Flour

- 6 Varying extraction rates

- 7 Blending of wholegrain and white flour

- 8 The colour of National Flour

- 9 Fortification of National Flour

- 10 Impact on livestock feed

- 11 Lessening of controls and discontinuation of National Flour

Cooking with National Flour

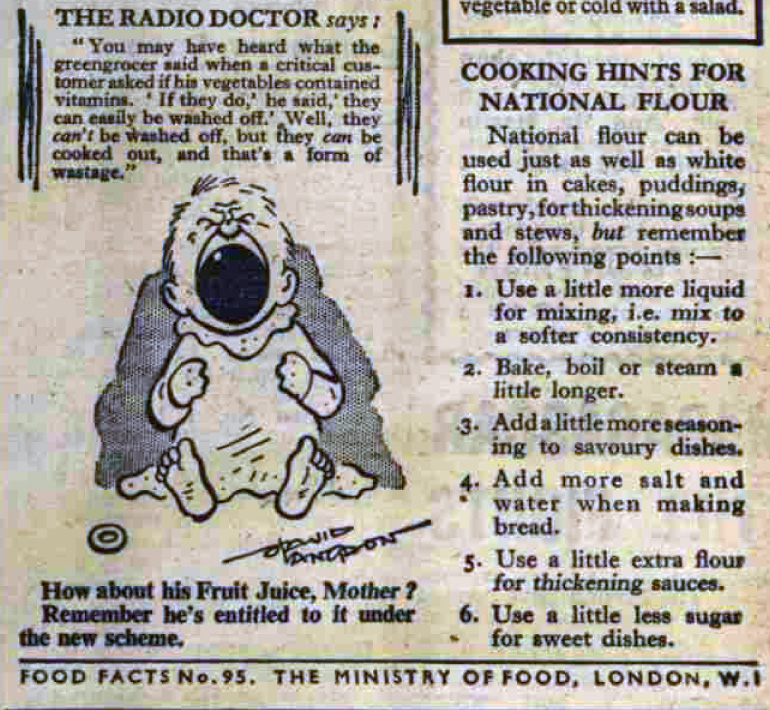

The Ministry of Food anticipated consumer objections, and so began a campaign to educate consumers how to adjust to life in the kitchen with national flour with printed material such as this:

Cooking Hints for National Flour

National flour can be used just as well as white flour in cakes, puddings, pastry, for thickening soups and stews, but remember the following points: —

1. Use a little more liquid for mixing, i.e. mix to a softer consistency.

2. Bake, boil or steam a little longer.

3. Add a little more seasoning to savoury dishes.

4. Add more salt and water when making bread.

5. Use a little extra flour for thickening sauces.

6. Use a little less sugar for sweet dishes.

This Week’s Food Facts. Food Facts No. 95. The Ministry of Food, London, W1. In: The Sunday Mirror. London, England. Sunday, 10th May 1942. Page 11, col. 6.

Note that if you are using World War Two recipes from the UK calling for National Flour, and you are using white flour instead, you may wish to do the opposite of the tips above.

Recreating National Flour

CooksInfo hasn’t yet been able to find a reputable source providing a formula for today’s historical cooks attempting wartime baking to approximate the flour at home.

To foster debate, and perhaps also to solicit guidance or correction from sources more knowledgeable about the skill of flour extraction, we offer the following as “grist for the mill”.

For our photo and recipe testing purposes, we have used the following “recipe” to “approximate” National Flour:

- 88 g of whole wheat flour

- 15 g of white plain / all-purpose flour

Sieve the wheat flour through a standard kitchen sieve, then add the white and mix.

The yield was 100 g (¾ US cup) of mixed flour plus 3 g (1 US tablespoon) of course material sieved out. (Starting with 88 g allowed for arriving at 85 g, or 85%, after sieving out the 3 g of coarse material.)

(Note: the actual ratios were adjusted up and down several times over the 14 years that National Flour was made, so if you are trying to approximate the flour for a specific year you will want to consult the ratios mentioned further below.)

National flour recreation, showing coarsest material sieved out. © CooksInfo / 2021

Obviously the sieve used is critical in this. This is a photo of the kitchen sieve used; it had no grading on it.

Sieve. © CooksInfo / 2021

The political purpose of National Flour

Wheat was a critical element in the UK rationing scheme which relied on unrationed bread to provide enough calories so that the population, for morale as well as fitness purposes, never felt hungry.

To avert the need for bread rationing, it was vital to make the wheat that made it safely from Canada across the Atlantic past the Nazi U-boats go a lot further in making bread than it normally did. This meant using more of the grain in grinding flour for the bread.

Primary use of National Flour

The primary use of National Flour was for bread made in bakeries and sold to consumers. This bread was called the National Loaf.

The flour was also sold for home use and was largely the only flour available for purchase.

Composition of National Flour

“National wheatmeal flour” was unbleached flour of 85% extraction (this % varied over the years) from hulled wheat grains. The flour had in it the starchy endosperm, the wheat germ, and the bran, with the coarser bran extracted out. 85% means that out of 100 kg of wheat grains, you would get 85 kg of flour. White flour is generally around 70% extraction, and would get you only 70 kg. The higher 85% extraction rate gets you an extra 15 kg of flour from that wheat.

“To cope with the reductions in the amount of wheat imported, more flour was extracted from the grain available. The extraction rate was raised to around eighty-five percent giving the population the nourishing wholemeal National Loaf (with a high vitamin B content), although many people did not find its greyish colour appealing.” [1]Forman, Jill. Foreword to: “Eating for Victory: Healthy Home Front Cooking on War Rations.” Reproductions of Official Second World War Instruction Leaflets. London: Michael O’Mara Books. 2007. Page 7.

National Flour was consequently similar to wholemeal (aka wholewheat) flour, but with some of the coarser bran removed, which in wholewheat flour is left in. For making bread, it usually had some white flour mixed in as well.

Varying extraction rates

The initial extraction rate was 85%, but it varied over the years. Furthermore, two extraction rates were often referred to: the actual initial extraction rate of the flour from the wheat, and the effective extraction rate after that flour was mixed with some white flour for bread use:

“After a short period during which the extraction rate for National Flour was raised to 90% the rate was reduced to 85% and remained so until August 1950, when it became 81%. This rate of extraction referred to flour as produced by the mills from the grist supplied. For issue it was usually mixed with a proportion (up to 20%) of imported white flour of lower extraction so that National Flour as delivered was comparable with 82-85% extraction flour.” [2]Fraser, J.R. Government Laboratory. National Flour Survey 1946 – 1950. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Volume 2, Issue 5, pages 193–198, May 1951

Figures on what the extraction rate was at any one time vary based on the source. It is likely that some sources look at effective extraction rates:

“In 1944, the 85% required extraction rate was lowered to 82.5 %, and then later that year, to 80%. [3]Bruce, Maye E. Common-Sense Compost Making By the Quick Return Method. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 1946. Chapter 5: Effect on Human Health.

Blending of wholegrain and white flour

White flour was still being produced and imported during this period, but it could only be obtained by food manufacturers for items such as biscuits, cakes, etc., or for mixing in small quantities into 85% extraction flour to make National Flour. Flour milled in Britain, whether from domestically-grown or imported wheat, was 80% extraction (by 1945.) Imported already-milled flour was 75% extraction. To make National Flour, the imported flour was mixed in with domestic flour at a rate of about 15% imported, 85% domestic. In Scotland, for some varieties of national bread such as batch bread, etc., bakers were allowed to mix in up to an extra 12 ½ % of imported flour. [4]Earl of Listowel in answer to Lord Hankey. House of Lords Debate. 02 May 1945. Hansard. vol 136 cc 155 – 6 155.

“In England, Wales and Northern Ireland the present overall extraction of national flour for bread-making, allowing for the addition of Canadian imported flour, is 79.25 per cent. The same figure also applies to Scotland, except for batch bread, where it may fall to 78.6 per cent. The only minerals for which routine analyses are carried out are calcium and iron. For these two elements the average contents in either the English or the Scotch loaf are approximately 610 and 12.5 parts per million respectively. The loaf which contained 85 per cent extraction home-produced flour also contained Canadian imported flour, and the corresponding figures were 620 and 17 parts per million.” — Viscount Clifden in answer to Lord Hankey. House of Lords Debate.08 May 1945. Hansard vol 136 c158 158.

This 1948 quote from the Minster of Food, John Strachey, gives more insight into the variances in blending by nation in the UK:

“Apart from very small quantities of the various improvers which are customary additions according to the types of wheat in use, the flour from which the national loaf is made is milled from a pure wheaten grist at 90 per cent extraction. Imported white flour is being admixed in the mills in England and Wales at the rate of 10 per cent. of the output and in Scotland and Northern Ireland at the rate of 15 per cent. Calcium is added at the rate of 7 ozs. per 280 lb. of flour. The usual practice of informing the public of any material change in the composition of national flour will certainly be continued.” — John Strachey, Minister of Food. National Flour (Composition). Debated on Monday 8 July 1946. Hansard Volume 425.

Overall, allowing that white flour was still being produced, Ministry of Food officials estimated that changing that extraction rate for the bulk of bread production requirements reduced the amount of wheat Britain required by about 10%.

The colour of National Flour

Consumers who had long been used to fine white wheat flour disparagingly described the colour of National Flour as “grey”. It was missing the larger particles of bran which would have moved the coloration from grey to brown. The amount of larger bran specks in the flour was constantly measured and referred to as “speckiness”:

“A summary of the colour index (bran speck contamination) data is given in Table 3. The colour index value expresses the speckiness as a percentage of that of an average 85 per cent National flour (colour index value 100). A flour with a colour index value of 0 would therefore be entirely free from visible bran specks.” — Colour Index and Granularity. National Flour (80 Per Cent Extraction) and Bread in Britain. Nature 157, 181–182 (1946). https://doi.org/10.1038/157181a0

The sieving standard used was a “No. 10 standard bolting silk”.

Fortification of National Flour

In addition to its higher extraction rate, National Flour was also a fortified flour with calcium and other vitamins added to it.

The decision to add calcium was opposed by some, but the Government based its decision on research done by Robert McCance and Elsie Widdowson, who recommended 120 mg calcium carbonate be added to each 100 g of 85% extraction National Wheatmeal flour [5]Widdowson, Elise May and Mathers, J.C. The Contribution of nutrition to human and animal health. Cambridge University Press, 1992. Page 383.. In practice, it was added at the rate of 14 oz. per 280 pounds of flour. The purpose of the calcium was to offset the higher rate of phytic acid in the higher extraction flour which impedes calcium absorption and can therefore lead to rickets in children (as happened in Dublin, where the calcium supplement was not added.)

“Throughout this period the grade of flour for home consumption has been controlled by the Ministry of Food. In addition to fixing the minimum permissible extraction-rate, the Ministry’s specification for National Flour has stipulated that it should contain the maximum quantity of the germ practically possible, that coarse bran should be excluded and that “creta praeparata” should be added at the rate of 14 oz. per sack of 280 lb. of flour (to offset the effect of the extra phytic acid expected with such a high-extraction rate.)” [Fraser, J.R. Government Laboratory. National Flour Survey 1946 – 1950. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Volume 2, Issue 5, pages 193–198, May 1951.[/ref]

The calcium was phased in gradually by various flour producers:

“We are indebted to Dr. R.A. McCance and Miss E.M. Widdowson for help and advice about this “fortification” of the loaf, as it is called in the United States… The writers mistakenly assumed that by the summer of 1942 all flour used in bakeries had an addition of calcium carbonate, and it was impossible at the end of the period of observation to find out which batches had been so treated, as the flour was derived from many sources. By Christmas 1942, i.e. approximately half-way through the investigation, about half the bread in the country, according to information available, was being fortified with calcium, and the proportion of bread so fortified steadily increased.” [6]Mackay, Helen M.M., Dobbs, R.H., Bingham, Kaitilin. The Effect of National Bread, of Iron Medicated Bread, and of Iron Cooking Utensils on the Haemoglobin Level of Children in War-Time Day Nurseries. London: Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1945 June; 20(102): pp. 56–63.

The calcium carbonate enhancement was added to the 85% extraction flour and to white flour, but it was decided not to add it to actual wholemeal (wholewheat) flour, as a result of some opponents who felt that calcium posed dangers:

“Wholemeal bread however, which because of the phytic acid content was most in need of fortification, was not fortified in deference to the pure food enthusiasts who bitterly opposed fortification as soon as it was proposed.” [7]”Dr. Elsie Widdowson, CH, CBE, FRS.” Medical Research Council, Cambridge University. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.mrc-hnr.cam.ac.uk/about/elsie-widdowson.html

The enrichment thus looked after the calcium issues that higher-grain bread can cause, but medical researchers began to express concern about the impact of the phytic acid in the flour inhibiting the absorption of iron. Even if the bread were fortified with additional iron, it still didn’t get absorbed by the body. [8]”At each nursery half the children received for five months National bread, made from 85 per cent extraction flour, and the other half the same bread fortified with 7 mgm. iron (reckoned as Fe) per ounce, which provided the children with far more iron than they could have obtained from natural sources. The average daily intake of bread by children aged one to five years was about 2 to 3 ounces, providing about 14 to 20 mgm. of additional iron. This medicated bread was without effect on the haemoglobin level or the morbidity rate. It is suggested that the phytic acid of 85 per cent extraction flour interfered with the utilization of the added iron. National bread made from 85 per cent extraction flour was itself without effect on the haemoglobin level over a period of five months. Iron cooking utensils were in use at one nursery but did not make an appreciable difference to the mean iron intake of the children as the consumption of cooked fruit was small….. This investigation supports the view that 85 per cent extraction flour is not a good vehicle for increasing iron consumption.” — Mackay, Helen M.M., Dobbs, R.H., Bingham, Kaitilin. The Effect of National Bread, of Iron Medicated Bread, and of Iron Cooking Utensils on the Haemoglobin Level of Children in War-Time Day Nurseries. London: Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1945 June; 20(102): pp. 56–63.

Impact on livestock feed

The higher extraction rate, incidentally, had a knock-on negative effect on the livestock feed industry:

“…higher extraction resulted in a loss of wheat offals with negative repercussions on livestock policy and availability of animal protein .” [9]Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. Bread Rationing in Britain, July 1946–July 1948, Twentieth Century British History, Volume 4, Issue 1, 1993, Page 68.

Lessening of controls and discontinuation of National Flour

The rules were adjusted again in 1953:

“When the milling industry was finally decontrolled in 1953, a Flour Order was made (Statutory Rules and Orders, 1953) which allowed the extraction rate to fall below 80% provided that the flour contained the minimum amounts of thiamin, nicotinic acid and iron recommended by the Conference on the Post-War Loaf (Ministry of Food, 1945). In addition the requirement to add chalk at the rate of 14 oz per 280 lb was continued. Bread made from National flour’ of 80% extraction rate was subsidized until 1956 but the millers were free to produce flour of a lower extraction rate to which the required nutrients had been added.” — Nutritional Aspects of Bread and Flour. Department of Health and Social Security. Report 23. 1981. ISBN 0 11 320757 3. 2.11, Page 5.

Production of National Flour was finally discontinued in 1956.

References

| ↑1 | Forman, Jill. Foreword to: “Eating for Victory: Healthy Home Front Cooking on War Rations.” Reproductions of Official Second World War Instruction Leaflets. London: Michael O’Mara Books. 2007. Page 7. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Fraser, J.R. Government Laboratory. National Flour Survey 1946 – 1950. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Volume 2, Issue 5, pages 193–198, May 1951 |

| ↑3 | Bruce, Maye E. Common-Sense Compost Making By the Quick Return Method. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 1946. Chapter 5: Effect on Human Health. |

| ↑4 | Earl of Listowel in answer to Lord Hankey. House of Lords Debate. 02 May 1945. Hansard. vol 136 cc 155 – 6 155. |

| ↑5 | Widdowson, Elise May and Mathers, J.C. The Contribution of nutrition to human and animal health. Cambridge University Press, 1992. Page 383. |

| ↑6 | Mackay, Helen M.M., Dobbs, R.H., Bingham, Kaitilin. The Effect of National Bread, of Iron Medicated Bread, and of Iron Cooking Utensils on the Haemoglobin Level of Children in War-Time Day Nurseries. London: Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1945 June; 20(102): pp. 56–63. |

| ↑7 | ”Dr. Elsie Widdowson, CH, CBE, FRS.” Medical Research Council, Cambridge University. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.mrc-hnr.cam.ac.uk/about/elsie-widdowson.html |

| ↑8 | ”At each nursery half the children received for five months National bread, made from 85 per cent extraction flour, and the other half the same bread fortified with 7 mgm. iron (reckoned as Fe) per ounce, which provided the children with far more iron than they could have obtained from natural sources. The average daily intake of bread by children aged one to five years was about 2 to 3 ounces, providing about 14 to 20 mgm. of additional iron. This medicated bread was without effect on the haemoglobin level or the morbidity rate. It is suggested that the phytic acid of 85 per cent extraction flour interfered with the utilization of the added iron. National bread made from 85 per cent extraction flour was itself without effect on the haemoglobin level over a period of five months. Iron cooking utensils were in use at one nursery but did not make an appreciable difference to the mean iron intake of the children as the consumption of cooked fruit was small….. This investigation supports the view that 85 per cent extraction flour is not a good vehicle for increasing iron consumption.” — Mackay, Helen M.M., Dobbs, R.H., Bingham, Kaitilin. The Effect of National Bread, of Iron Medicated Bread, and of Iron Cooking Utensils on the Haemoglobin Level of Children in War-Time Day Nurseries. London: Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1945 June; 20(102): pp. 56–63. |

| ↑9 | Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. Bread Rationing in Britain, July 1946–July 1948, Twentieth Century British History, Volume 4, Issue 1, 1993, Page 68. |