freefoodphotos / freeimageslive.co.uk / CC BY 3.0

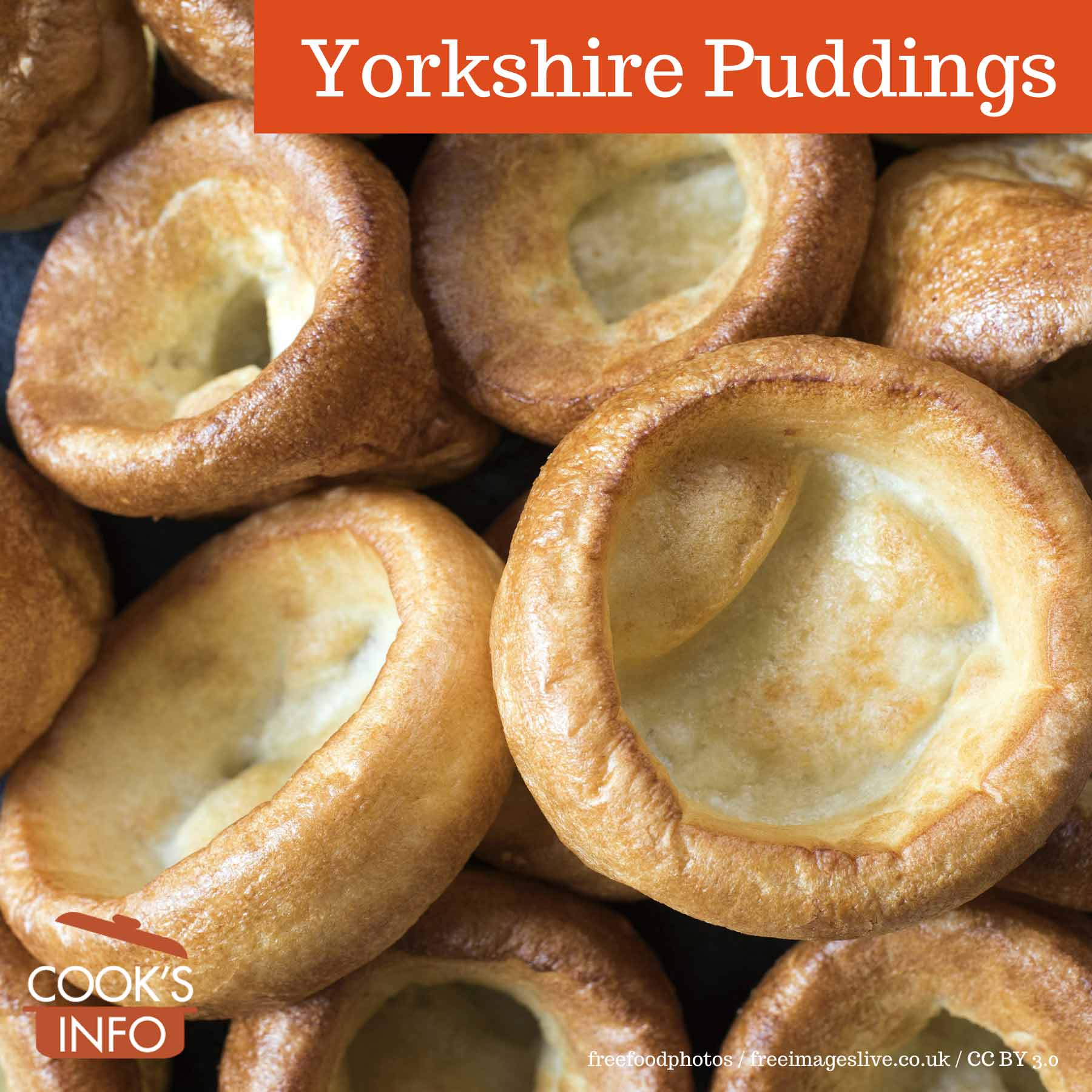

Yorkshire pudding is a plain puffed pastry served with the savoury part of a meal, whose origins harken back to the county of Yorkshire in England.

See also: Popovers, Yorkshire Pudding Day, Yorkshire Pudding Recipe

What is a Yorkshire pudding?

It is not a pudding at all, in the dessert sense, but instead a plain-flavoured but rich-tasting crisped-up hollow shell made from a pourable batter. Yorkshire pudding should be airy, light and crisp, and be just a touch soft — but not soggy — inside.

It is similar to popovers, but it’s not meant to rise quite as high or be as airy. Like all things simple and homey, though, Yorkshire pudding is the subject of much debate. People like it the way they like it.

The batter is made from eggs, milk and flour, and traditionally baked in beef drippings. Occasionally, very occasionally, an adventurous cook will try to jazz it up, by adding perhaps sage and fried onion to the batter, or even from time to time a handful of currants. American versions often call for butter or some kind of fat in the batter, and use all milk, instead of milk and water. Purists say that’s a version of a pop-over, and not a real Yorkshire recipe — all the fat needed comes from what is in the pan.

Yorkshire pudding batter, with muffin tin. John Wilbanks / wikimedia / 2006 / CC BY-SA 2.0

You can buy package mixes for the Yorkshire batter, and in the UK, you can even buy bags of frozen, fully-cooked individual ones that just need heating. In Canada, the Loblaw’s grocery chain also sells bags of frozen Yorkshires under its President’s Choice brand name that have been imported from Yorkshire itself (valid as of 2021).

Cooking methods

Yorkshire can be cooked as individual puddings, or as one large one that is cut up into pieces and served. Some people prefer the individual ones, saying they puff up and brown more nicely. They also like the cavity that forms in the middle of each, letting it act as a bowl to hold lots of gravy. You can use muffin tins for the individual ones, or you can buy special Yorkshire pudding “muffin tins” that have much shallower, flatter cups in them.

In the UK, Yorkshire pudding is cooked in beef dripping, which you can buy in blocks in stores. In North America, oil is used. Beef dripping isn’t available at stores, and the amount of dripping from one roast isn’t enough, nor is it available in time during the run-up to dinner to get the Yorkshires started in the oven. Butter is not a good substitute for dripping as it can’t stand the high heat; it will burn on you. Even when cooked in oil, though, Yorkshires are still nice with some drippings from the beef spooned on them, but then that leaves you the challenge of having enough drippings for the gravy. The solution may be to ask your butcher for an extra piece of fat when you buy your roast.

Serving Yorkshire pudding

In the past, Yorkshire pudding was served as a course on its own before the meat (the theory is that people would be less hungry and the meat would go further after that.) The habit of whether to serve it with the main meal or before the meal varies even in Yorkshire by region. Many of those in Yorkshire who eat the pudding before the meal regard the custom of eating it with the meal as “odd” and think it’s a southern English habit. But, reputedly those from the east coast of Yorkshire are more inclined to have it with their meal than those from the north or south of the county.

Even though, in theory, we all have food enough in plenty nowadays negating the need to fill people up before the meat is served, some people contend that serving the Yorkshires in advance gives the roast the time it needs to rest before carving it. Generally, though, given the last minute flurry of activity with all roast dinners, having to buy time for the roast to rest usually isn’t a problem as it will end up resting, anyway.

Some people even serve Yorkshires after the meal — in Yorkshire, leftover Yorkshire puddings are sometimes served as a dessert, with jam or treacle.

Some restaurants in England (such as Toby’s Carvery) even serve them at breakfast (as of 2021).

There is nothing, by the way, saying that Yorkshires can only be made to go with roast beef. Some people feel that no roast dinner, be it lamb, pork or even chicken, is complete without a few Yorkshires making an appearance. In the North of England, some pubs even sell them as a stand-alone snack with onion gravy on them, or as an accompaniment to steak and kidney pie.

Pubs and fast food places now increasingly make very large ones to act as bowls, which they stuff with other ingredients to act as a meal all in itself. They are also being made in long, flat form now to be rolled up as “Yorkshire pudding wraps” in food inside.

A large Yorkshire pudding acting as a bowl to hold mashed potato and stew. Mr Barndoor / wikimedia / 2014 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Aunt Bessie’s Yorkshire Puddings

The Aunt Bessie’s Yorkshire pudding factory in Hull, Yorkshire, England makes close to 5,000 of the puddings a minute. The brand started in 1995.

They only use five ingredients and nothing else: flour, egg, powdered milk, water, and salt. Their trays are greased with canola oil (aka rapeseed oil).

Many feel that the company makes perfect Yorkshires, with a slightly “soggy bottom, where there’s real flavour; bread-y walls, for texture and substance; and a satisfying crispy top.”

The company makes both regular-sized and giant-sized ones. [1]Barrie, Josh. National Yorkshire Pudding Day: How Aunt Bessie’s factory makes 639,095,954 puddings a year at its factory in Hull. London, England: i (newspaper). 3 February 2019. Accessed July 2019 at https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/food-and-drink/national-yorkshire-pudding-day-aunt-bessies-factory-hull/

Cooking Tips

Never use self-rising flour, or any kind of baking powder — though you might think it would help make lighter and puffier Yorkshires, it actually turns out flat ones with soggy puddings.

Some say the batter should be left to stand first before pouring into the pans; some even say that chilling the batter first makes the Yorkshire puff more. Others say there is no basis for either of these ideas, and that neither “trick” makes any difference. Those whose grandmothers let it stand or chilled it, though, are loathe to deviate from the techniques.

Everyone agrees, however, that the pan and the fat in the pan must be heated first before the batter is added. If this isn’t done, the Yorkshires won’t rise or crisp. The fat in the pan has to be hot, very hot, to crisp the outside edges of the pudding: the fat should sizzle as you pour the batter in. For individual puddings, you want about 1 tablespoon of oil / fat in each individual muffin cup.

You can heat the pan with the fat in the oven, or you can just heat it and the fat on the stovetop burners (if your pan has a solid enough bottom that it can stand direct heat and if you have any stove-top burners free at that point.)

If you are making one big Yorkshire, to serve 6 to 8 people make a pudding in a tin 12 x 10 inches (30 x 25 cm). For 4 people, use a tin 11 x 7 inches (28 x 18 cm).

Yorkshires must be cooked in a very hot oven, about 225 C (425 F). As this is a much hotter temperature than you would be cooking the roast at, it can be a puzzle how to reconcile the two needs. Experts advise:

- Aim to remove the roast just under 10 F (3 or 4 degrees C) short of the temperature you are aiming for it to be cooked to;

- 10 minutes before you are ready to cook the Yorkshire, crank the oven up to 225 C (425 F) get it hot for the Yorkshires;

- Remove the roast from the oven. Cover the roast, and let it rest. The temperature will keep on rising and it will keep on cooking inside while the Yorkshires are cooking, and it will stay piping hot for 20 to 30 minutes because it is covered, which gives you enough time for the Yorkshires;

- Put the Yorkshire pudding in the oven to cook;

- A large one generally takes about 30 to 40 minutes;

- Individual ones about 20 to 25 minutes

Some people say “never peek”, but quick peeks don’t actually hurt.

Nutrition

Aunt Bessie’s 6 Delicious Large Yorkshire Puddings (0.5g salt per 27.5g portion) [2]2010 study done by Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH). As quoted in: Jamieson, Alastair. Salty Sunday roast dinners are putting Britons at risk of premature death. London: Daily Telegraph. 5 December 2010.

History Notes

Yorkshire pudding was originally flatter than today’s puffy version. Meat was roasted on a spit by a fire. The batter was cooked in a pan below it to capture all the fat and juice drippings from the meat. Our bodies need some fat in our diets in order to absorb certain vitamins. Unlike today’s situation where there are so many easy sources of fat for us, fat was hard to obtain in northern countries. Cooking the Yorkshire under the meat would ensure that none of the valuable (not to mention tasty) fat and juices were wasted.

In 1737, a recipe for something called “Dripping Pudding” appeared in a book called “The Whole Duty of a Woman”. The next known printed occurrence for the recipe is in 1747, in the “Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy” by Hannah Glasse, where it is being called “Yorkshire Pudding”.

In 2008, the British Royal Society of Chemistry decided that, based on the chemistry of baking, a Yorkshire had to be at least 4 inches (10 cm) tall to qualify as a Yorkshire pudding:

” A Yorkshire pudding isn’t a Yorkshire pudding if it is less than four inches tall, says the Royal Society of Chemistry. The Society has ruled on the acceptable dimensions of the Yorkshire pudding and is now issuing the definitive recipe. The judgement followed an enquiry from an Englishman living in the Rockies in the USA who emailed the RSC seeking scientific advice on the chemistry of the dish following a string of kitchen flops.” [3]Yorkshire pudding must be four inches tall, chemists rule. Press release. Royal Society of Chemistry. England. 12 November 2008. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.rsc.org/AboutUs/News/PressReleases/2008/PerfectYorkshire.asp

Literature & Lore

A Yorkshire pudding boat race was held for three years in Brawby, Yorkshire, on Bubb’s Lake. The boats were made of Yorkshire pudding, lined with foam-filler, and varnished on the outside to make them water resistant. The race suggested by a man named Simon Thackray. It was run by a government-funded arts group in Yorkshire called “The Shed”, but only seems to have run for 3 years from 1999 to 2001, though the group has copyrighted the name.

Sources

Hayward, Tim. Scientist reveals formula for perfect Yorkshire pudding. Manchester: The Guardian. 13 November 2008.

References

| ↑1 | Barrie, Josh. National Yorkshire Pudding Day: How Aunt Bessie’s factory makes 639,095,954 puddings a year at its factory in Hull. London, England: i (newspaper). 3 February 2019. Accessed July 2019 at https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/food-and-drink/national-yorkshire-pudding-day-aunt-bessies-factory-hull/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 2010 study done by Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH). As quoted in: Jamieson, Alastair. Salty Sunday roast dinners are putting Britons at risk of premature death. London: Daily Telegraph. 5 December 2010. |

| ↑3 | Yorkshire pudding must be four inches tall, chemists rule. Press release. Royal Society of Chemistry. England. 12 November 2008. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.rsc.org/AboutUs/News/PressReleases/2008/PerfectYorkshire.asp |