Butter tarts. © Denzil Green / 2010

Butter tarts, as made in Canada, are tarts made with melted butter, brown sugar, egg, walnuts, and white vinegar. The mixture is spooned into tart shells and baked. Home-baked versions often have a thin crust. Commercial bakery versions often have a thick crust.

Raisins versus nuts

Some purists say the above ingredients are all that a butter tart should have in it, but in fact, that’s a recent school of thought. There are firmly-established, long-seated traditions that include raisins, or currants, or walnuts, or a combination of raisins or currants and walnuts. The earliest printed versions call for currants.

Many people prefer butter tarts now with neither nuts nor raisins, just the filling.

In the early 2000s, a butter tart craze saw ingredients such as chocolate chips, bacon, cheesecake chunks, etc being added to butter tarts, particularly for novelty sale at events such as fairs and exhibitions.

A butter tart with raisins. Denzil Green / 2010

Filling variations

How dark the tarts are depends on how dark the brown sugar is.

Some recipes swap in lemon juice for the vinegar. Though vinegar was the original ingredient, the swap for lemons shows the evolution of lemons becoming more affordable over time. The purpose of the vinegar is to cut back a bit on the sweetness, and as it is stronger tasting, vinegar can do a better job of that than lemon juice can do.

The cooked filling may be more runny, or it may end up more solid and slightly puffed (sometimes referred to as “set.) Some versions of the filling end up with a golden sugar crust on top, some do not; it all depends on the recipe. Some runnier versions since the 1930s swap the brown sugar for corn syrup. The tarts can be deep or shallow.

Popular in Scottish settlement areas

The dessert originated in Scotland where it is still made as “Ecclefechan Tarts” and was brought to Canada by Scottish settlers (see History section below.)

Butter tarts are particularly popular in the provinces of Ontario and Nova Scotia where there were heavy areas of Scottish settlement, though in recent years there has been encouragement to think of them as a pan-Canada dessert.

Butter tart close relations

Canadian butter tarts are very closed related to American pecan pie (which generally adds cornstarch to the filling) and pecan tassies from Georgia, and to Scottish Ecclefechan butter tarts.

In fact, depending on the Canadian butter tart recipe version, and the Scottish butter tart recipe version, the two can be identical.

The main differences today between the two cousin butter tarts, seen particularly in commercially-sold versions, are that:

- The Scottish version tends to be more packed with fruit, while the Canadian version is much stingier with the fruit. Some Scottish versions particularly at Christmas use mixed fruit, including candied cherries now for a splash of colour, though historically in Scotland just using currants was more common;

- In the Scottish version, the filling acts as a binding for the plentiful fruit and nuts, while the Canadian version emphasizes instead the filling as the main ingredient, sometimes even omitting the fruit and nut altogether;

- In the Scottish version, the nuts, though traditionally walnuts, can now sometimes be almonds for a fancier touch. In the Canadian version, if nuts are present, they will almost always be walnuts as the Scottish settlers in Canada could easily obtain those for free from the trees around them. (The American version from the State of Georgia, Pecan Tassies, uses pecans, as they were easier to obtain in that area.)

- The Scottish version is sometimes made as one large pie; butter tarts in Canada are never, though pecan tassies are often expanded into “pecan pie”.

A wag could point out that the economic use of expensive dried fruit was an achievement on the part of Canadians at outdoing the Scots on frugality.

Butter tarts as “tartlets” in frozen tart shells. This is a common “cheat”. Glen Wilkinson / wikimedia / 2011 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Butter tarts as recruit in search for Canadian culinary identity

In October 2019, Alexandra Kazia of the Canadian Broadcasting Company’s radio service wrote a piece on butter tarts. In it, she acknowledged the current attempts to use the butter tart as a vehicle for Canadian identity. “If there’s one dessert food that’s widely touted as quintessentially Canadian, it’s probably the butter tart… These simple, gooey, incredibly sweet tarts are a national treasure, even appearing on a Canada Post stamp.” [1]Kazia, Alexandra. The sweet, sticky and sometimes divisive history of the butter tart. Toronto, Canada: CBC. 14 October 2019. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.cbc.ca/radio/history-of-butter-tarts-1.5316827

Liz Driver, author of Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, reinforces Kazia’s point by appealing to patriotic emotions and encouraging an end to any quest for the dessert’s origin beyond Canada’s borders. “Perhaps the most Canadian thing about the butter tart is the assumption that it was created somewhere else… Why is it that we can’t just accept that we made something ourselves? It’s absolutely completely believable that something did sort of rise up out of the grassroots.” [2]Ibid.

The present author disagrees, but acknowledges that it is perhaps particularly believable especially when a food item has a flag wrapped around it. There has been a deliberate attempt to lasso butter tarts as a vital part of Canadian identity. Lenore Newman, author of Speaking in Cod Tongues: A Canadian Culinary Journey, says that giving food a national identity is “often an overt political act” and points out that the idea of Canadian cuisine really didn’t exist until 1967. [3]Ibid.

Not everyone in Canada identifies with butter tarts, however, either as a cultural or culinary item. They have been primarily an eastern, not western, Canadian thing, though as is often the case, people in Ontario tend to assume that whatever is true for them is true for Western Canada as well (Ontarians in Eastern Canada believe erroneously that bagged milk is everywhere in Canada.)

And, Ann Hui, a food reporter for Toronto’s Globe and Mail’s newspaper, does not buy into butter tarts as a pan-Canadian, national dessert. “As a national icon, as being our national dessert … I just think we’re better than the butter tart… In 2019, with the Canada that we have now that is so diverse and is so rich with people from different cultures and different perspectives, I think that maybe it is a good time to revisit those icons and those ideas of what a Canadian symbol is and isn’t.” She points out that for Canadians whose heritage involves different cuisines, they will likely find butter tarts cloying and sickly sweet, and therefore not identify with them at all. [4]Ibid.

Hui feels that anything trumpeted as a national dessert should be something everyone can enjoy, particularly as cultural, and culinary, diversity in Canada accelerates.

What might be unique to Canada is the kind of desperate longing for a food item to call its own. Not many would dispute that New York City is one of the best places in the world to get pizza, often pizza that is better than that made in Italy. Still, no one in in New York would dispute that pizza was of Italian origin. But, that doesn’t diminish one bit the fact that New Yorkers are a dab hand at making it. The same should be true for butter tarts: they may be a thoroughly Scottish dessert, right down to the tooth-aching sweetness of them, but that doesn’t diminish for one second the quality and variety of butter tarts being made in Canada.

Cooking Tips

Shortening the cooking time results in a slightly runnier tart, which some people prefer.

Storage Hints

Butter tarts freeze well. For best quality, freeze in air-tight containers or tightly-sealed freezer bags for up to six months.

History Notes

The popular press assumption in Canada is that butter tarts sprang out of nowhere in Canada with no antecedents, making them a uniquely Canadian food. The Collins English Dictionary states, incorrectly we believe, that “butter tarts” are “one of only a few recipes of genuinely Canadian origin.” This fits in well with both food marketing and cultural nationalism purposes.

CooksInfo does not support this theory for the following reasons:

- Canadian butter tarts are nearly identical to Ecclefechan butter tarts of Scotland, despite recent culinary evolution of the recipe in both countries;

- Ecclefechan butter tarts in Scotland have been made since before Robbie Burns was born;

- The two butter tart epicentres in Canada of Ontario and Nova Scotia were both heavy centres of Scottish immigration;

- The earliest Canadian butter tart print recipes are attributed to people with distinctly Scottish surnames;

- Heavy areas of Scottish immigration in the American South became the birthplaces of butter tart’s kissing cousins, pecan pie and pecan tassies;

- An alternative name for Ecclefechan tarts is “border tarts” (as Ecclefechan is close to the English border.) Some food historians believe that “butter tart” is a linguistic corruption of “border tart.”

It staggers belief that a practically identical recipe just happened to be created out of the blue in regions where the immigrant families would have known an identical recipe from back home.

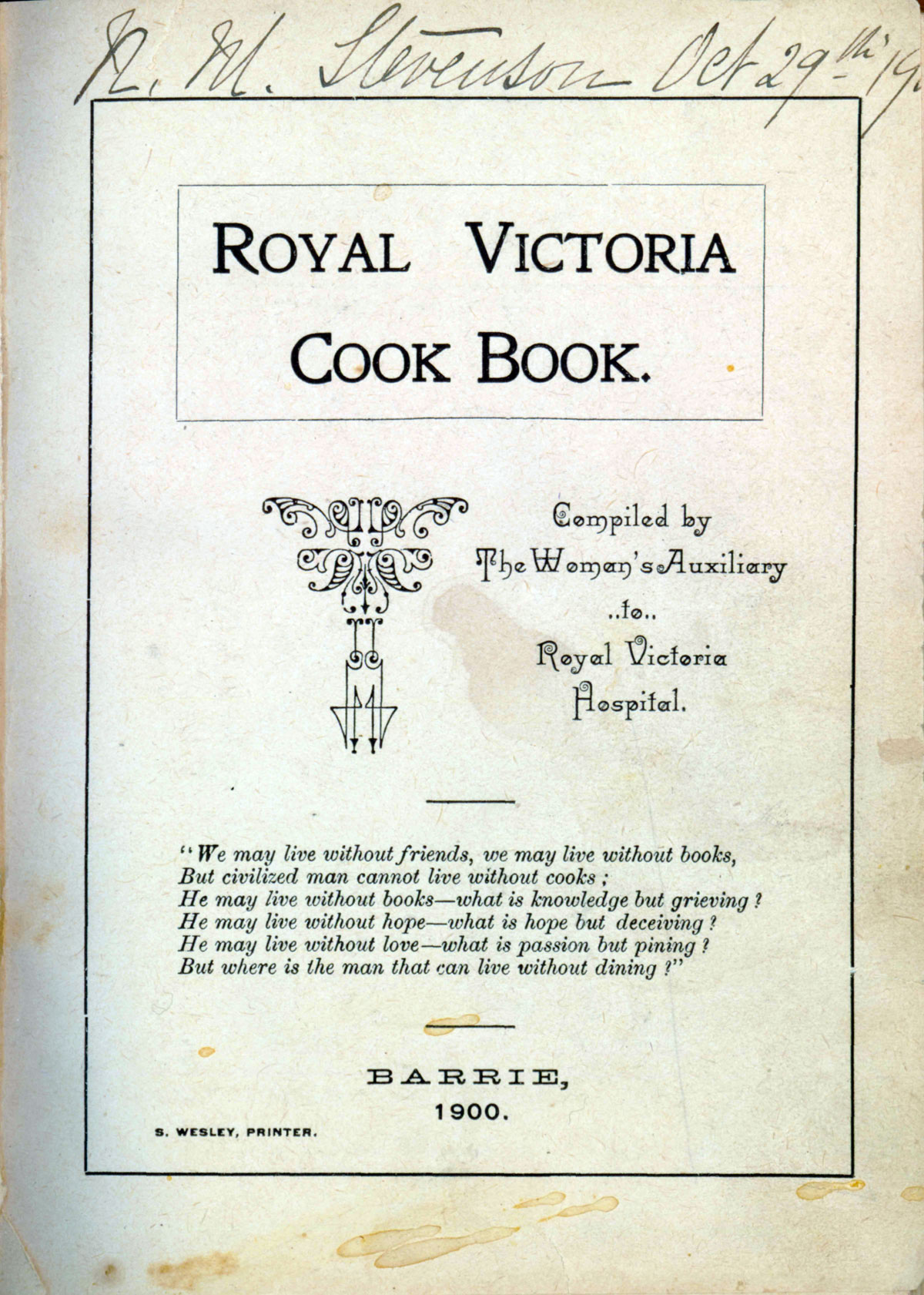

The first printed reference found (to date) in print in Canada to butter tarts is in a 1900 cookbook published by The Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Barrie, Ontario. The recipe appeared on page 88 of that book in the “Pies” chapter, titled simply “Filling for Tarts.” It is attributed to Mrs. Malcolm MacLeod. [5] Jacobs, Hersch (2009), “Structural Elements in Canadian Cuisine”, Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures 2 [6]Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Country Country Now Magazine. 12 February 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501

Opening of the Royal Victoria Hospital, 1897, Copyright: Public Domain

Royal Victoria Cook Book, 1900. Pg. 1, Copyright: Public Domain

Butter tart recipe on middle of left-hand page. Royal Victoria Cook Book, 1900. Pp. 88-89. Copyright: Public Domain

A 1909 printed recipe from Parkside, Winnipeg referred to them as “Currant Tarts.” [7]Selected Recipes. Ladies of Young Street Methodist Church. 1909. As mentioned by: Baird, Elizabeth. The Sweet Treat Debate. Canadian Living Food Blog. 15 December 2009. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.canadianliving.com/blogs/food/2009/12/15/the-sweet-treat-debate/

In 1911, “Three recipes for tart filling and six recipes for butter tarts appear in the ‘Canadian Farm Cook Book.'” [8]Bonisteel, Sara. Butter Tarts, Canada’s Humble Favorite, Have Much to Love. New York: New York Times. 12 January 2018. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/12/dining/butter-tarts-canada.html

Ruplins Baking Co. in La Crosse, Wisconsin advertised something they called “Butter Tarts” as part of their Christmas 1912 lineup. [9]Advertisement in La Crosse Tribune. La Crosse, Wisconsin. 23 December 1912. Page 10.

One factor that almost certainly contributed to butter tart’s popularity in homes, at church suppers and at bake sales was that they were “store-cupboard staples”: they could be made out of what you would usually have to hand in your dry storage, along with two other items (butter and eggs) that everyone would have in their cool storage and later fridge. “If you look at the ingredients, it’s really what you have in your pantry when you have nothing else,” said Liz Driver, the author of “Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825–1949.” [10]Bonisteel, Sara. Butter Tarts, Canada’s Humble Favorite.

Butter tarts. Pixel1 / Pixabay.com / 2015 / CC0 1.0

Who was Mrs Malcolm MacLeod — Mary or Margaret?

There has been a quest to find Mrs MacLeod’s first name.

Some writers believe her name was “Mary.” “All that turned up in the archives was that her first name was Mary, and that she lived at 12 Toronto St [Ed: Barrie]. Her husband’s profession was listed, but illegible.” [11]Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Cottage Country Now. 12 February 2008. Accessed October 2019 at http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501

Researchers at the Simcoe County Archives, Ontario, give their backing to the first name of Mary as well:

“The 1901 Canadian Census of Barrie included a Malcolm MacLeod family living at 12 Toronto Street, not far from the hospital. Mrs. Malcolm MacLeod’s first name was Mary and, according to the information recorded by the enumerator, she was born in rural Ontario on December 15, 1855.” [12]Simcoe County Archives. Mrs. Malcolm MacLeod and her recipe for butter tart filling. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.simcoe.ca/Archives/Pages/Mrs-MacLeods-Butter-Tarts.aspx

They go further and give her middle names and birth and death dates as well: Mary Ethel (Cowie) MacLeod (ca 1855-1915).

An amateur genealogist, however, feels that the first name was Margaret. Beth Mills, genealogy enthusiast and owner of Legacy Book Barrie, “has been researching family trees for the past few years. She spent two hours researching two websites and came up with the full history of Mrs. Malcolm… the inventor of the butter tart is Margaret MacLeod who lived her entire 73 years at or near Hawkestone.” [13]Douglas, Donna. Mrs. MacLeod DOES have a first name! 25 February 2008. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.donnadouglas.com/columns/barrie-advance/mrs-macleod-does-have-a-first-name.html

For what it’s worth, the Simcoe County Archives researcher seems to have a more compelling case, having presented actual copies of a census and obituary to reinforce their case for “Mary.”

Alternative histories

You will hear alternative histories for butter tarts

- That the recipe came over from France between 1663 and 1673 with Les Filles du Roy to Quebec, and lay dormant and hidden for over 230 years until it suddenly spring to life and appeared on the pages of Mrs MacLeod’s recipe book in Ontario;

- That the recipe has its roots in Quebec Sugar Pie and made a mysterious, untraceable journey to small town Ontario;

- That the recipe has its roots in Georgia Pecan Tassies and made its way up from the States;

- That the recipe was immaculately conceived out of the blue in a vacuum.

Literature & Lore

Mrs Malcolm MacLeod’s 1900 “Filling for Tarts” recipe, as adapted by Katherine Elphick [14]Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Country Country Now Magazine. 12 February 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501 [Ed: The original recipe is just 17 words, and 2 lines, long. The type of sugar was not indicated, and no baking directions were given.]

FILLING:

1 cup currants

1 cup brown sugar.

1 / 2 cup salted butter, softened

2 large eggs, slightly beaten

PASTRY:

12 tart-sized pastry shells

Put currants in medium-sized bowl and cover with boiling water for five to ten minutes. Drain currants, discard water, and place currants back in the same bowl. Whisk in brown sugar and butter, and combine well. Blend in eggs.

Spoon filling into tart shells until three-quarters full (make sure currants in the liquidity mixture are evenly distributed in each shell).

Bake in bottom third of 400 F oven for about 15 to 20 minutes, or until filling is puffed and bubbly and pastry is golden. Let stand on rack for 1 minute. Immediately run flat metal spatula around tarts to loosen (this will help prevent sticking). After five minutes, carefully slide spatula under tarts and transfer to rack to cool. Makes 12. [15]Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Country Country Now Magazine. 12 February 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501

Language Notes

The name “butter tart” is a bit of a misnomer, implying that butter is the featured ingredient, whereas in fact, it’s sugar.

Some people speculate that it is a corruption of the Scottish phrase “border tart.” “Border tart” is an alternative name for Ecclefechan butter tarts, the antecedent of Canadian butter tarts. Ecclefechan butter tarts were sometimes called “border tarts” because Ecclefechan is a town in the south of Scotland near the English border.

Sources

Legue, Suzanne. Butter tarts soar from ‘bucket list’ to bestseller. Cottage Country Now Magazine. 29 April 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/379975

Butter tarts with a thick crust. Rob Campbell / wikimedia / 2012 / CC BY 2.0

References

| ↑1 | Kazia, Alexandra. The sweet, sticky and sometimes divisive history of the butter tart. Toronto, Canada: CBC. 14 October 2019. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.cbc.ca/radio/history-of-butter-tarts-1.5316827 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid. |

| ↑3 | Ibid. |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Jacobs, Hersch (2009), “Structural Elements in Canadian Cuisine”, Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures 2 |

| ↑6 | Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Country Country Now Magazine. 12 February 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501 |

| ↑7 | Selected Recipes. Ladies of Young Street Methodist Church. 1909. As mentioned by: Baird, Elizabeth. The Sweet Treat Debate. Canadian Living Food Blog. 15 December 2009. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.canadianliving.com/blogs/food/2009/12/15/the-sweet-treat-debate/ |

| ↑8 | Bonisteel, Sara. Butter Tarts, Canada’s Humble Favorite, Have Much to Love. New York: New York Times. 12 January 2018. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/12/dining/butter-tarts-canada.html |

| ↑9 | Advertisement in La Crosse Tribune. La Crosse, Wisconsin. 23 December 1912. Page 10. |

| ↑10 | Bonisteel, Sara. Butter Tarts, Canada’s Humble Favorite. |

| ↑11 | Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Cottage Country Now. 12 February 2008. Accessed October 2019 at http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501 |

| ↑12 | Simcoe County Archives. Mrs. Malcolm MacLeod and her recipe for butter tart filling. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.simcoe.ca/Archives/Pages/Mrs-MacLeods-Butter-Tarts.aspx |

| ↑13 | Douglas, Donna. Mrs. MacLeod DOES have a first name! 25 February 2008. Accessed October 2019 at https://www.donnadouglas.com/columns/barrie-advance/mrs-macleod-does-have-a-first-name.html |

| ↑14 | Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Country Country Now Magazine. 12 February 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501 |

| ↑15 | Elphick, Katherine. RVH cookbook boasts one of first, printed butter tart recipes. Country Country Now Magazine. 12 February 2008. Retrieved October 2012 from http://www.cottagecountrynow.ca/cottagecountrynow/article/387501 |