Early 1900s ice cream maker. Bengt Oberger / wikimedia / 2012 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The 9th of September is Ice Cream Freezer Patent Day.

It celebrates the invention of the world’s first homemade ice cream machine. It operated on the principle of salted ice drawing the warmth out of a cream mixture to freeze it: many home ice cream makers today still draw on the same principle, though they are electrified now.

#IceCreamFreezerPatentDay #IceCream

See also: Ice, Cream, Salt, Ice Cream, Ice Cream Day, Chocolate Ice Cream Day, Creative Ice Cream Flavours Day, Frozen Yogurt Day, Ice Cream Soda Day, Hot Fudge Sundae Day, Peach Ice Cream Day, Soft Ice Cream Day, Strawberry Ice Cream Day, Vanilla Ice Cream Day

External resources: Enjoying Homemade Ice Cream without the Risk of Salmonella Infection (FDA)

Nancy M. Johnson’s Patent September 1843

The patent for the world’s first hand-cranked freezer was awarded to Nancy M. Johnson of Philadelphia on the 9th of September in 1843.

She received US Patent 3,254 for an “Artificial Freezer”: “Be it known that I, Nancy M. Johnson, of the city of Philadelphia and State of Pennsylvania, have invented a new and useful Improvement in the Art of Producing Artificial Ices….”

To use her device, you put a container of liquid ice cream mixture into another larger container packed with ice and salt, and cranked by hand until the ice cream was frozen. She even gives a tip in her patent on how to save money on expensive salt: “When the economy of salt is particularly important, I effect it by evaporating the salt water derived from the salt and ice, thus making a very limited quantity of salt serve for an indefinite number of successive operations.”

Note that she doesn’t claim to have invented the hand-cranked method; merely to have made improvements in it.

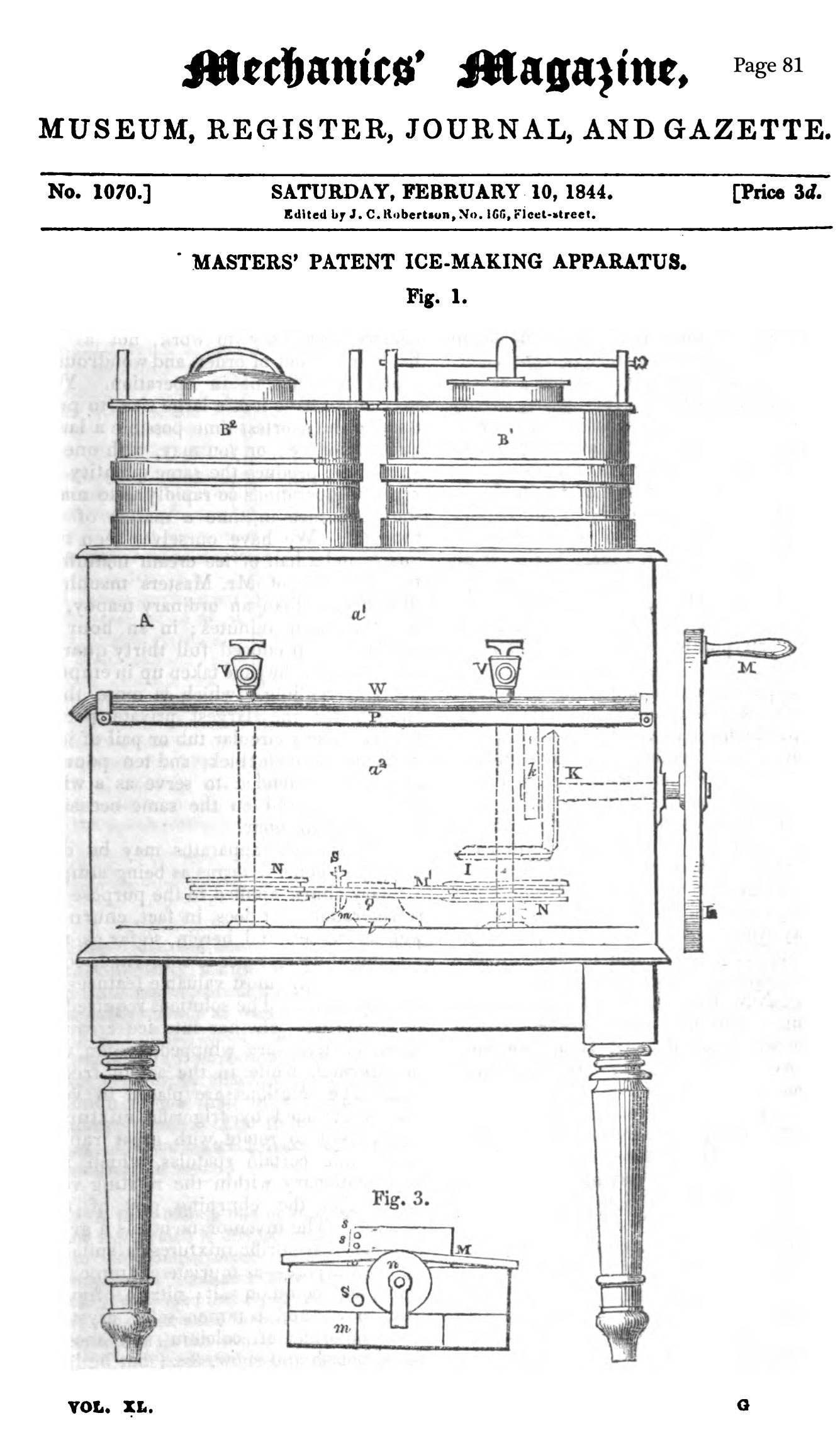

Thomas Master’s Patent January 1844

In England, Thomas Masters also invented a machine to make ice cream and other ices. The patent information says “dated 6 July 1843, enrolled 6 January 1844.” There is no patent number because prior to 1852, British patents were not issued numbers. [1]”Before 1852 English patents were not numbered. The numbers now associated with these early English patents were assigned to them retrospectively after this date.” — Find early British patents. British Library. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.bl.uk/help/find-early-british-patents Our understanding is the “enrolled” means “granted”, so his patent was granted approximately four months after Nancy Johnson’s.

Mechanics Magazine. 10 February 1844. Vol. 1070. Page 82.

Mechanics Magazine. 10 February 1844. Vol. 1070. Page 81.

Masters followed up with a book in 1844 called “The Ice Book” (London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1844) in which he illustrated and described his patented ice cream maker, as well as giving recipes for it. The ice cream recipes included Mille-fruit Ice Cream, Brown Bread Ice Cream, and Ratafia Ice Cream, as well as Vanilla, Orange, Strawberry, and Lemon.

William G. Young’s Patent 1848

Another US patent was awarded five years later. On 30 May 1848, William G. Young of Baltimore, Maryland, received US Patent 5,601 for “An Improvement in Ice-Cream Freezers.” [2]There were only fourteen patents issued that day, and William G. Young’s was the only one of those fourteen for an ice cream maker — despite what you might hear about Johnson’s being patented on this date as well.

“Many devices have been resorted to for expeditiously freezing ice-cream, but all have found to be defective. The best now in use is that known as “Johnston’s”, [3]Mispelling of Johnson in Young’s submission. which is, like the ordinary freezer, with a revolving shaft inside it, on which are two curved wings that move round and cause the cream to revolve in the freezer and be thrown to the outside. I find that the operation is greatly facilitated by causing the freezer itself to move rapidly as well as the cream inside. To effect this I construct the freezer with the cover firmly attached….”

Food poisoning from an ice cream maker

In 1847, the Adams Sentinel of Pennsylvania reported that an early adapter had already figured out how to give people food poisoning from misuse of an ice cream maker:

“Caution To Ice-Creamers. The Nantucket Inquirer of the 9th inst. says: “A quantity of lemon ice cream had been put into a tin freezer on Tuesday morning, and allowed to remain there, in a liquid state, until Wednesday noon, when it was frozen, and about thirty gentlemen and ladies ate pretty freely of the cream. The consequence was that they were all made sick, a few of them so severely, that for an hour or two during the night, it was feared they would not recover. All, however, are now convalescent. The action of the acid in the mixture on the tin lining of the freezer for more than twenty-four hours produced an active poison, and the sufferers may congratulate themselves that they escaped with only being made sick. A tin vessel of vanilla cream stood unfrozen in the same way, from Tuesday till Wednesday, but those who ate of that were not at all injured by it.” [4]Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Adams Sentinel. 19 July 1847. Page 1.

Note that the reporter assumes it was the interaction of the acidity of the lemon with the tin, though it could also have been that bacteria in the milk may have been able in the warmth to multiply to levels sufficient enough to make the diners ill.

References

| ↑1 | ”Before 1852 English patents were not numbered. The numbers now associated with these early English patents were assigned to them retrospectively after this date.” — Find early British patents. British Library. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.bl.uk/help/find-early-british-patents |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | There were only fourteen patents issued that day, and William G. Young’s was the only one of those fourteen for an ice cream maker — despite what you might hear about Johnson’s being patented on this date as well. |

| ↑3 | Mispelling of Johnson in Young’s submission. |

| ↑4 | Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Adams Sentinel. 19 July 1847. Page 1. |