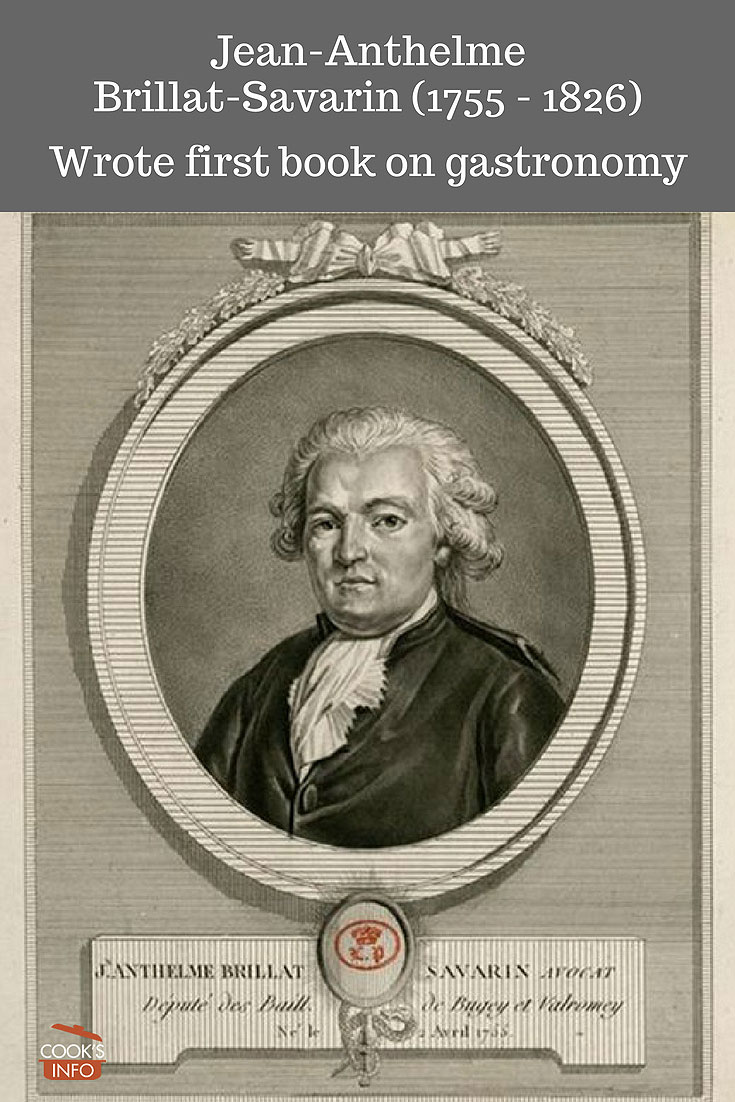

Portrait de Brillat-Savarin. Public Domain

Brillat-Savarin, while not a chef, has been one of the most influential food writers of all time. He is known for his book Physiologie du Goût (translated variously into English as “The Physiology of Taste”, “The Philosopher in the Kitchen”, etc.)

Many food items have been named in his honour, including a cheese and a garnish.

See also: À la Brillat-Savarin, Brillat-Savarin Cheese, Timbale Brillat-Savarin, Brillat-Savarin Birthday

Brillat-Savarin’s Objective

He worked on his book Physiologie du Goût over the course of many years. He kept notes in the breast pocket on his coat wherever he went. At times, he would even take the manuscript to work with him at the courts (he was a lawyer by trade), and sneak in time to work on it. He also often brought his beloved hunting dog, Ida, to “work” with him at the courts in Paris where she would sit beneath his chair.

Some of the work is pedantic, but immensely readable all the same, thanks to his many anecdotes and sense of humour. The style is quite rambling, in the observational manner of the period.

Brillat-Savarin’s goal was to raise cooking to a level of true science. He wrote in a era — the early 1800s — when “taste” in music, literature and art was thought to be something objective that educated people could share and agree on. A writer for The Economist called “The Physiology of Taste “one of those delightfully dilatory, observational works at which his age excelled.” [1]Fasman, Jon. Technology can help deliver cleaner, greener delicious food. London, England: The Economist. 2 October 2021. Accessed October 2021 at https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2021/09/28/technology-can-help-deliver-cleaner-greener-delicious-food

In Brillat-Savarin’s view, if you put a well-prepared dish in front of someone, how he or she reacted told you not whether the dish was good or not (because you already knew that it was), but rather how educated the person was. In his mind, excellence was not based on what the French court might say, or what celebrity chefs might dictate, but rather on the intrinsic quality of ingredients prepared with care.

He strove to put forward what he felt could be called general, universal principles, rather than, as a contemporary of his Grimod de la Reynière did, putting forth personal preferences. In his book, he is not French-centric, but rather points out all the food stuffs from different parts of the world that were enriching the tables in Paris. What he praised was not upper-class aristocratic cooking, but the middle-class and provincial cooking that he loved. Most of the memorable meals recounted in Physiologie du Goût are very simple ones.

The French author Baudelaire later criticized the book, because he felt Brillat-Savarin didn’t pay enough attention to wine.

Brillat-Savarin aimed to make links between food and its effects on the body and health, as well as on the mind and spirit. In his chapter “On Obesity”, he focussed on people who eat a great deal of rice, potatoes and bread, and writes: “the chief cause of corpulence is a diet with starchy and farinaceous elements” and later, “The second of the chief causes of obesity is the floury and starchy substances which man makes the prime ingredients of his daily nourishment. As we have said already, all animals that live on farinaceous food grow fat willy-nilly; and man is no exception to the universal law.” When the low-carbohydrate Atkins diet was in fashion at the beginning of the 21st century, many people used this chapter to show how ahead of his times they felt he was in some aspects.

His Life

Brillat-Savarin was born 1 April 1755, the eldest of what would come to be eight children in Belley in Bugey, a region halfway between Lyon, France and Geneva, Switzerland. The house, at 62 Grande-Rue, is still extant.

62 Grande-Rue, Belley. View from interior courtyard. Groumfy69 / Wikimedia / 2012 / CC BY-SA 3.0

His mother (Claudine-Aurore Récamier) was a good cook. His father, Marc-Anthelme Brillat, a lawyer, was a gourmet. Two of his brothers would also be gourmets: one was also a lawyer in Belley, the other was a colonel of the 134th infantry regiment. His sister, Pierrette, would die at the age of 100, just having finished dinner in bed and calling for her dessert.

He was born with his father’s last name, Brillat, but one of his aunts said that he would be her heir, provided he agreed to keep her last name alive. The family agreed to this, making his last name Brillat-Savarin.

He decided to become a lawyer like his father. He studied at Collège de Belley (the same college where the French poet Lamartine would later study), then at the age of 19 he studied in Dijon (some people think that it was Lyons instead.) He returned to Belley at the age of 23 in 1778, having obtained his law licence, and began to practise.

In 1789, at the age of 35, he was elected to Estates General to represent Belley in the Third Estate at Versailles (the French revolution sprang out of these meetings.) Brillat-Savarin was not a very revolutionary soul — after all, life was good for him and his family — and he soon annoyed all his fellow revolutionaries by arguing against the introduction of the jury system, for the retention of the death penalty, and against reorganizing France into départements. One person he particularly annoyed was Robespierre, who ironically (given his later history) was arguing for the death penalty to be abolished.

Brillat-Savarin returned back to Belley in the fall of 1791. His region had been reorganized into the new département of Ain, and he returned home as the president of the newly created civil tribunal for that département. In August 1792, however, when the monarchy finally fell, he was booted out of that position by authorities in Paris, who saw him as too Royalist. But in December 1792, the people of Belley twigged their noses at the new authorities, and elected him Mayor. For the next year, he tried to protect Belley from the excesses of the Revolution that were washing out from Paris, but as the Terror set in, he found himself in danger from the enemies he had made earlier in Paris, who saw him as a counter-revolutionary. In December 1793, his property was seized and he had to flee.

He became an exile outside of France. He passed through Cologne and stopped first in Lausanne, Switzerland (which he’d later recount in his book), then in the Netherlands, then finally in the United States, where he spent two years, teaching French lessons and playing violin in the John Street Orchestra in New York. He even owned a Stradivarius, which he had managed to get out of France, and it was this instrument that he played in the orchestra.

In the United States, he lived in Boston, Hartford (Connecticut), New York and Philadelphia. In his book, he recounts a turkey shoot in Connecticut.

He was allowed to return to France in 1796. The French consul-general lent him the money for his return voyage. He landed in Le Havre, France, in August 1796. Once back in Belley, he was able to recover title to much of his property.

Brillat-Savarin was appointed to the staff of General Augereau, who would later become Marshal Augereau, and was put in charge of catering for the general staff that was fighting on the Rhine at the time. When this was finished, he was first appointed to the Court of Criminal Justice in Versailles in May 1798, then shortly after on the 9th April 1800 to the “Cour de cassation” (Supreme Court of Appeal.) A few days later, the Minister of Justice announced that all the members of the Cour de cassation would hold their positions for life. Brillat-Savarin was set.

Brillat-Savarin never married. He spent ten months of every year in Paris, and the remaining two months in the summer in Belley with two of his sisters who also never married. He was interested in archaeology, astronomy, chemistry, and food. He spoke five languages, and knew Latin and Greek (as he would have needed to for his studies back then.) He loved music and played violin.

Bronze bust of Brillat-Savarin in Belley, France. Akela3 / wikimedia / 2007 / CC BY 3.0

The feast day of the saint he was named after, Anthelme, is 26 June. Every year, he would invite anyone he knew in Paris who was from Belley to his home for a dinner, and serve wine from the region. Saint-Anthelme is also the patron saint of Belley Cathedral.

In 1808, he was made a Chevalier de l’Empire by Napoleon, in recognition of how he had tried to protect Belley during the Revolution.

Early 1900s postcard, France. Public Domain

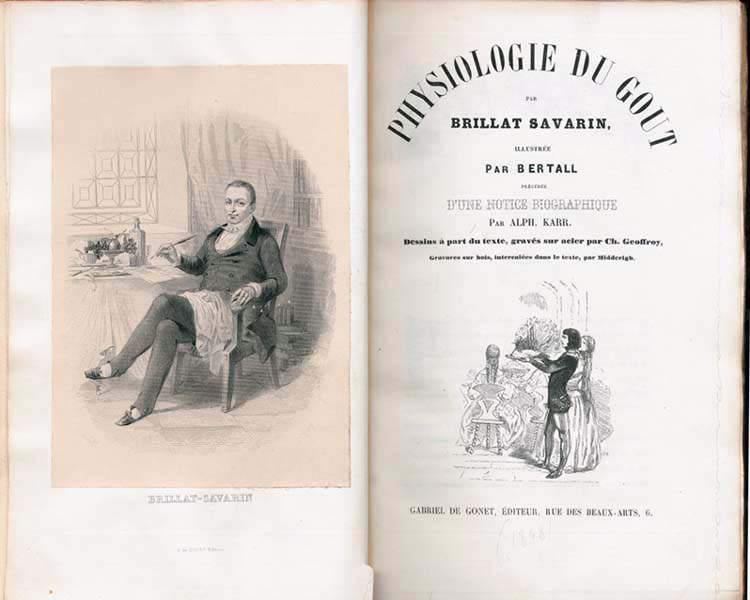

His book appeared in print in December 1825, published anonymously, two months before his death at the age of 70 in February 1826. He paid for the publication himself. The publishing was handled by A. Sautelet.

The full title of the book is actually: “Physiologie du Goût, ou Méditations de Gastronomie Transcendante; ouvrage théorique, historique et à l’ordre du jour, dédié aux Gastronomes parisiens, par un Professeur, membre de plusieurs sociétés littéraires et savantes” (The Physiology of Taste, or meditations on transcendental gastronomy. A theoretical, contemporary and historical work dedicated to Parisian gastronomes, by a professor, member of several literary and scholarly societies.”)

Title page of “La Physiologie du Goût” (“The Physiology of Taste”) by French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) with a portrait of the author. 1848 edition

Mu / wikimedia / 2006 / Public Domain

On 18th January 1826, he received an invitation for a memorial mass for Louis XVI at St Denis basilica. He hadn’t particularly wanted to go, but the invitation — from his “boss”, the “First President of the Court of Appeal”— had pointedly noted that if he showed, it would be the first time he had bothered to show up for something like this, so he went, even though he had a bad cold at the time.

In the draughty, cold basilica, he was so chilled that his cold turned into pneumonia which proved to be the end of him (two other of his fellow members of the court bench also literally caught their death at the same mass.)

He died in his Paris home at 11, rue des Filles Saint-Thomas.

Plaque apposée au n° 11 de la rue des Filles-Saint-Thomas, Paris 2e. « Brillat-Savarin, auteur de La Physiologie du goût, né à Belley, le 2 avril 1755, est mort dans cette maison le 2 février 1826. » Mu / Wikimedia / 2010 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Some sources state he died on the 2nd of February; others, however, say the 1st of February, and that is what his tombstone says as well. He was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris (Division 28 of the cemetery.) His tombstone reads:

“Ici repose Jean Anthelme Brillat de Savarin, Membre de l’Assemblée Constituante, Conseiller à la Cour de Cassation, Né a Belley le 1 avril 1755, Mort à Paris le 1er fevrier 1826.“

The “de Savarin” inscribed on his tombstone was an affectation that he had come to use, and that others seemed to humour; using the “de” instead of the hyphen implies nobility.

Tomb of Brillat-Savarin. Père-Lachaise – Division 28. Pierre-Yves Beaudouin / Wikimedia Commons / 2012 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The centenary of his death was celebrated in 1926 by a banquet at the Savoy Hotel in London, with guests including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

“The centenary of Brillat-Savarin, the patron saint of gourmands, was celebrated on Tuesday with a unique luncheon at the Savoy Hotel, London.

Brillat-Savarin was a French lawyer and the author of a famous book on the physiology of taste.

One of his aphorisms is: ‘The discovery of a new dish does more for the happiness of mankind than the discovery of a new star.’

For a month, Francois Latry, the chef, had been searching Europe to provide the courses that were served at the lunch, which lasted two hours.

Special dishes were made to cook the food as Brillat-Savarin would have had it prepared and served.

The menu consisted of five courses, which were probably the most delicious that have been served in London. The wines were equally choice.

A century back cocktails were unknown. There were no cocktails.

There were 56 guests, among those present being Count A. de Fleuriau (the French ambassador), Sir Squire Bancroft, Sir Landon Ronald, Sir Arthur Stanley, Sir Conan Doyle, Mr Augustine Birrell, Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, and Senator Marconi.

Brillat-Savarin held that ceremony and the thought of having to make a speech interfered with the enjoyment of food; there was no reception and no speeches.” — Lunch Without Speeches: Gourmands’ Patron Saint. Cardiff, Wales: The Western Mail. Wednesday, 27 January 1926. Page 4, Col. 2.

Other Books by Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

- The Handbook of Dining Corpulency and Leanness Scientifically Considered

- Essai historique et critique sur le duel: d’après notre législation et nos mœurs. Paris, Caille et Ravier, 1819

- De la cour suprême. Deuxième fragment d’un ouvrage de théorie judiciaire. Paris, Impr. Testu, 1814.

Literature & Lore

“Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es,” or, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” (Now paraphrased, though inaccurately, as “you are what you eat”.) — Brillat-Savarin

In “Lady Chesterfield’s Letters to Her Daughter”, Lady Constance Chesterfield writes of Brillat Savarin:

“As to M. Brillat Savarin, whose Physiologie du Goût is the text-book of the fine kitchen-stuff writers, many of his notions on cookery are fantastic, and many more repulsively coarse. A pretty gastronomic taste must the man have possessed whose formula for eating a “fat little bird” is to take him up with your fingers, cram him into your mouth, and craunch [sic] him, bones and all! Faugh!” — Sala, George Augustus. Lady Chesterfield’s Letters to Her Daughter. London: Houlston and Wright. 1860. Page 90.

The writer Philip Morton Shand, the grandfather of Camilla Shand, wife to Charles, the Prince of Wales, wrote:

“Chemical nutrition… so confidently forecasted by Brillat-Savarin as the gastronomic achievement of future generations, has come to stay, but in a form he could scarcely have dreamed of in the most troubled of his many nightmares.” — Philip Morton Shand: A Book of Food. 1927.

References

| ↑1 | Fasman, Jon. Technology can help deliver cleaner, greener delicious food. London, England: The Economist. 2 October 2021. Accessed October 2021 at https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2021/09/28/technology-can-help-deliver-cleaner-greener-delicious-food |

|---|