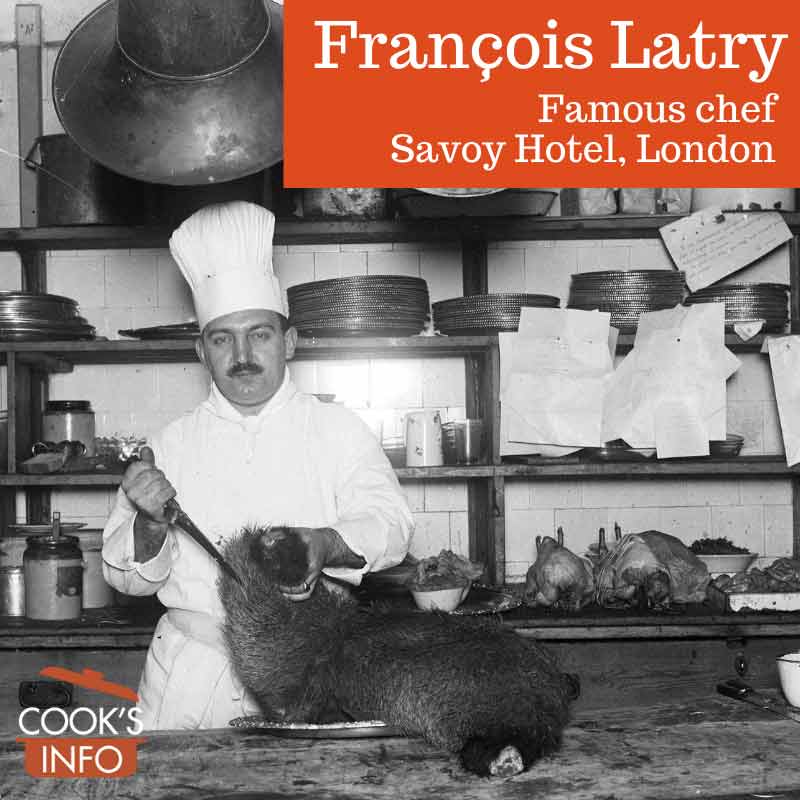

Roast bear figured on the Christmas menu at the Savoy Hotel in 1921. The dish has not been served in this country since the days of King Henry VIII. François Latry, chief Chef at the Savoy, carving. 27 December 1921. Smith Archive / 1921 / Alamy.

François Latry (1889-1966) was “maître chef” at the Savoy Hotel in London for 23 years, from 1919 to 1942. Today, he is remembered particularly for the Second World War rationing recipes he helped create for Lord Woolton at the Ministry of Food, particularly the one named “Woolton Pie.”

His life has not yet been well-documented; what we know of him comes just from newspaper coverage of the time. Fortunately, he was a media darling and was frequently in the press, as well as a frequent writer of letters to the editor of the Times of London.

Early years

François’s mother started started to teach him to cook when he was very young. “He was only seven when, having, approximately, seen the light of day near where Brillat-Savarin was also born, he began watching his mother, a great cordon blue, and doing little things under her direction.” [1]De Cordova, R. Thumbnail interviews with the great: Genuis en casserole. London, England: The Sphere. Saturday, 16 October 1926. Page 118, Col. 3.

When he was 12, he went off to work in a hotel in Bresse, and then at the age of 14, he undertook 10 years of apprenticeship training in hotels in Lyons and Paris. “At twelve his future was settled. He was sent to learn his art in one of the best hotels in Bourgen-Bresse, whence the best French poultry comes. Then he went to Lyons for ten years before he migrated to Paris to get finished off, if there is such a thing as being finished off in the fine art of cooking.” [2]De Cordova, R. Thumbnail interviews with the great: Genuis en casserole. [3]“M. Latry was born in Gex (Ain), France, and received his first cooking lessons at the age of 10 from his mother, herself a cook of note. An apprenticeship begun at 14 took him through ten years of training in the best hotels of Lyons and Paris.” In: “Chef to Sovereigns quits London Post.” New York Times. 11 March 1942.

Savoy Hotel

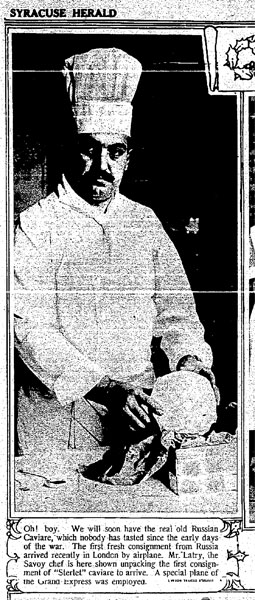

Latry in 1921, already appearing in the American press. Syracuse Herald. Syracuse, New York, USA. 25 December 1921. Page 7.

Latry started with the Savoy in London in 1911 when he was approximately 22 years old. After some time away working in another hotel, and serving in the army, he returned in 1919 to the Savoy to become its head chef.

“Coming to London, the Savoy, in 1911, engaged him as its second chef. Two years later he was chef of its Café Parisien, which he left to go to Claridge’s for five years, a service interrupted by a year at the front, where his leg was so badly injured that he was discharged as unfit for further service. After the Armistice, he returned to the Savoy as chief chef at a far younger age than anyone had ever previously been appointed to so important a position.” [4]De Cordova, R. Thumbnail interviews with the great: Genuis en casserole.

At the end of that same year, he fed 1,250 people for New Year’s Eve 1922 at a banquet accompanied by pipers:

“Whilst the Old Year was passing out and the New Year coming in, London danced and made merry.

Between seven and half-past eight in the evening traffic in the Strand from Trafalgar Square in the West to St Clement Danes in the East, was blocked with cars making their way to the Savoy Hotel, where every table had been booked for the New Year’s Eve ‘Venetian Night’ gala banquet and ball.

An elaborate banquet was served containing, among other dishes, three entirely new creations of Francois Latry, the famous Savoy Hotel Chef. Souvenirs from Paris and New York, and thousands of favours were distributed to the 1,250 guests present. Over 35,000 crackers were pulled. Dancing with the famous Savoy-Havana Band (the largest dance orchestra in the world) and three other dance orchestras, went on in four ballrooms. The full regimental band of the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders played in the foyer during the banquet.” [5]London Makes Merry: Amazing Scenes in Hotels and Streets. Nottingham, England: Nottingham Evening Post. Monday, 1 January 1923. Page 1, Col. 2.

In 1924, he made a specially commissioned chocolate Easter egg, filled with diamonds and jewellery worth £7,000 at the time.

In 1925, he was acclaimed for having created a new dish, “Supreme de Volaille sous Cloche Savoy”:

“Gourmets the world over will undoubtedly be glad to know that a new dish has been discovered. Francois Latry, of the Savoy Hotel, has labored and produced “Supreme de Volaille sous Cloche Savoy.” This new tid-bit is wing of chicken which is neither boiled, braised, grilled nor roasted. Francois refuses to disclose how it is cooked. It is brought to the table in a glass dish with a glass bell cover, and the last stage of the cooking is performed over a charcoal fire before the very eyes of the gourmet. The only vegetable entering into the cooking is the button mushroom. Just as the dish is served a small quantity of whipped cream is placed over it. The gourmets rave over it and it’s not expensive, oh not so very expensive, $3 a portion or so!” [6]Church, David M. INS Staff Correspondent. Daily NewsLetter: General News and Gossip from Staff Writers at Home and Abroad. In: The Oxnard Daily Courier. Oxnard, California, USA. 9 January 1925. Page 2.

In 1927, he apologized to Charles Lindbergh for using alcohol in the dishes he served him, as he did not know Lindbergh was a tea-totaller:

“Humbly and profuse as only a Frenchman could phrase it, Francois Latry, chef at the Savoy hotel, New York [Ed: should be London] has sent a wireless message to Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh in which he “craves a thousand pardons” and “also those of your mother.” Francois’ grief is due to the fact that he “used many wines and fine liquors in dishes you honored in eating at Grands Savoy banquet.” He seeks forgiveness because “no one tell me till this day you abstain — I take to myself responsibility most unhappy happening. [sic]” Evidently Francois’ pastry artistry is second only to his typical French sense of courtesy.” [7]In the Spotlight of Today’s News. Waterloo Evening Courier. Waterloo, Iowa, USA. 16 June 1927. Page 1.

By 1928, he had received many job offers in the United States, but refused them on account of prohibition there at the time:

“America is taking so many of the best chefs from England… Maitre Latry, the chef of the famous Savoy Restaurant, has received several tempting offers from the United States, but prefers to remain in London. He believes no good chef will cook without wine.” [8]US Bids and London Chefs. Charleston Gazette. Charleston, West Virginia, USA. 22 July 1928. Page 7.

On 31 May 1928, he was named to the Board of Directors of the “Société des Grands Hôtels de la route Paris-Nice” in France . His position at the time was given as “directeur des cuisines du Savoy-Hotel”; his address at the time was given as 132 Cromwell Road, South Kensingston, London. [9]Société des Grands Hôtels de la route Paris-Nice, Article 75, III. In: le Memorial d’Aix. Aix-en-provence. 13 juillet 1932. Page 4.

In 1929, Latry put all the chefs that worked under him on slimming diets:

“London: In the belief that the only successful chefs are slim ones the management of one of the largest hotels in London has put all its cooks on a rigid diet. Economy in the kitchen they say has nothing to do with the edict. M. Latry the famous French chef who is now Maitre de Cuisine at the Savoy hotel is responsible for the order which has caused little short of a sensation around the kitchen stoves of London’s hoteldom.” [10]Cooks Go On Diet to Do Their Work Better. New Castle News. New Castle, Pennsylvania, USA. 5 April 1929. Page 28.

In the same year, he also introduced a children’s menu to the Savoy:

“Parents who take their children to exclusive restaurants will appreciate the enterprise of Chef Latry of the Savoy Restaurant who has developed a series of harmless dishes made to look like the delicacies adults enjoy. “Lobster” is produced from a mixture of potatoes and white sauce and milk service in a lobster shell. Semolina, colored to the right tint, takes the place of caviar. Other luxuries indigestible for children are similarly imitated. Parents are now able to enjoy a peaceful meal without having to explain to their young why this or that must be deferred until the child is older.” [11]Children Now May Dine on Imitation Delicacies. Chronicle Telegram. Elyria, Ohio, USA. 2 August 1929. Page 12.

In 1934, he wrote the introduction to “Wine in the Kitchen” by Elizabeth Craig.

Also in 1934, he was admitted to the French Legion of Honour:

“A complimentary dinner to M. Francois Latry, maitre des cuisines of the Savoy Restaurant, was held at the Savoy Hotel last night to celebrate M. Latry’s recent admission to the Legion of Honour. Vicomte du Poulpiquet du Halgouet, French Commercial Attaché in Great Britain, presided and on behalf of the French Government formally invested M. Latry with the Cross of a Chevalier of the Legion. Mr G. Reeves-Smith, vice-chairman and managing director of the Savoy Hotel, Limited, proposed the health of M. Latry…… M. Eugène Herbodeau, president of the Association Culinaire Française, also spoke to this toast.” — Honour for London Chef. The Times. London. 30 October 1934. Page 17.

In 1935, he helped judge a cooking contest for the British army:

“A British army cook has won the Jubilee World Championship Vegetable Soup Contest against 600 competitors…. Francois Latry, famous French chef, with Henri Cedard, formerly the King’s chef at Buckingham Palace (now retired), and Iwan Kriens, chairman of the Food and Cookery Association, were the judges. They awarded first prize to Staff-Sergeant Brown, of the British Army School of Cookery at Aldershot…” — Russell, Henry Tosti. United Press Staff Correspondent. “Iowa Housewife Wins Honor in World Prize Soup Contest. Middlesboro Daily News. Middlesboro, Kentucky, USA. 30 July 1935. Page 3.

In 1936, he advised on kitchen equipment, restaurant tables, and bread-making machinery for the Queen Elizabeth ocean liner. [12]National Museums Liverpool, Maritime Archives and Library. B/CUN/3/7/3/1 14 Nov 1936 – 30 Sept 1940.

In October 1937, he was awarded the diploma of the Club des Cent, an elite French gastronomic group founded in 1912.

In autumn 1938, Latry visited New York:

“The warrant and occasion for these eat-all doings was the arrival for three days only of Francois Latry, of the Savoy in London, since the death of Escoffier the ranking chef of Europe….The lunch next day at “21” was, however, the high point in M. Latry’s grand tour…Contrary to the general rule which provides that chefs must be solemn fellows, M. Latry is stoutish and very merry. By the time the singing was under way he was conducting “Sur Le Point d’Avignon” with a menu….” [13]Beebe, Lucius. This New York. Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California, USA. 9 October 1938. Page 2-A.

The American Culinary Federation held a special dinner for him:

“When the American Culinary Federation tossed a dinner for Francois Latry, chef of the Savoy hotel, London, here [Ed: New York] the other day, the menu was:

1. Varieties of Circumstance (Your guess is as good as mine, but it has something to do with caviar, smoked sturgeon, smoked turkey, and hot hors d’oeuvres.)

2. Essence of tomato.

3. Soft shell crabs on swordfish, southern style (with steamed potatoes on the side.)

4. Young squab turkey of Minnesota; gratin of artichokes and peas. (Why Minnesota? Don’t ask me.)

5. Cranberry sherbet.

6. Salad – Lettuce with tarragon on Virginia ham.

7. Souffle Ice Cream Gastronome; coffee.” [14]Dale Harrison’s New York. Printed in: Press-Citizen. Iowa City, Iowa, USA. 4 November 1938. Page 11.

Savoy Hotel Lobby. Martin vmorris / flickr / 2011 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Final years

Latry retired in March of 1942.

“Francois Latry, long recognized as the leading chef of Europe, has retired as maitre chef des cuisines of the Hotel Savoy of London on account of ill health, it was disclosed yesterday. Marius Dutrey (c. 1888 – 1975) has been appointed his successor.” [15]Chef to Sovereigns Quits London Post; Francois Latry of Hotel Savoy Retires Because of Health. New York Times. 1942.

Latry died in August 1966 in France. The Times noted that the announcement was made from (Latry’s hometown) of Gex, though it didn’t necessarily state that was the place of death.

“The inventor of the ‘Woolton-pie’, a vegetable pie whose recipe was used by almost every wartime housewife, M. Francis Latry, formerly Maitre chef de cuisine of the Savoy Hotel, London, has died, aged 70, it is announced from Gex, France. After the war he returned to France to become a hotelier.” [16]Woolton pie creator dies. The Times, London. Wednesday, 17 August 1966. Page 1.

He had a son, Roger Latry. He sent his son to a French school in London, and then to the Ecole hôtelière de Lausanne. Roger would become an English agent in France during the Second World War, working with the French resistance. Later in life, Roger ran the inn “Relais de l’Empereur” in Montélimar, France. [17]Études Drômoises. Revue du patrimoine Drômois. Montélimar : différents articles. Au relais de l’Empereur, Par J. Delatour – N°1 de 1999 p. 20 à 25. Retrieved April 2011 from http://etudesdromoises.free.fr/pages/pages_revue/resumes_d_articles/special_montelimar.htm

Latry’s Successors

Marius Dutrey stayed until January 1946. In January 1946, Camille Payard was awarded the post, but occupied it only shortly as he died in October of that same year.

Here is a timeline of head chefs at the Savoy from 1919 to 1965:

- Francois Latry: 1919 to 1942

- Marius Dutrey : 1942 – 1946

- Camille Payard: January to October 1946 (died age 44 in the position)

- August Laplanche, head chef from 1946 to 1965

François Latry and WWII

During 1940 and 1941, Latry was an object of interest in the American press to see how a “haute cuisine” chef was faring in the face of rationing.

Robert Bowman, of CBC Radio, Canada, talked to Latry live in his kitchens:

“And so, just after the air raid warning is announced, the dancing goes on at the Savoy Hotel. The Savoy of course is one of London’s most famous hotels, upstairs are suites named after the Gilbert and Sullivan Savoy Operas. Below stairs are the kitchens and cellars, and even in war time London, few spots are busier on a Saturday night, air raid warning or not, than the Savoy kitchen. Bob Bowman of the CBC is stationed there now, with a Savoy chef, Monsieur Latry; take over will ya Bob.

“Hello, we are switching you now from the upper dance room down to the kitchen here and what you’re hearing is not excitement because of an air raid, but just the busy orders providing people with meals there. And of course I’m sure your all licking your lips because this kitchen as probably a lot of you will know is provided over by no less a person than François Latry who certainly, one of the most famous chefs in the world. As a matter of fact, his culinary ability has brought him honors from many parts of the world. He’s a chevalier of the French Legion of honor and he also is a holder of the Order of the Cordon Rouge which was established by Queen Mary. Well tonight he’s presiding over this white tile kitchen with its red floors. His battery of chefs and flying black coated waiters, who are serving those people who are staying on right now, staying on and still dancing upstairs. It’s war time and we have rationing, nevertheless, I don’t think you’d notice any difference at all. The menu tonight includes eight hors d’oeuvres including caviar, eight different kinds of meat and game, and nevertheless I don’t want you to think that we’re living luxuriously, sort of out of keeping with the war effort. Printed in red letters on the menu is this sentence: “By agreement with the Ministry of Food, only one dish of meat or fish or poultry may be served at a meal.” Still that’s not a great hardship is it, not to be able to have both fish and meat, and even at that the genius of Mr. Latry comes into effect because he’s designed marvelous (French dish) and (another French dish) as he calls them, which have a fish base and which can be served before the main course. Things like…things like Crab Maryland and all that sort of thing. Well, here he is François Latry in his tall white cap. François Latry one of the world’s most famous chefs.

I’m very happy to say hallo to my friends across the Atlantic, and to tell them we are well, and food is plentiful. The war has not effected my cooking.

Well, hasn’t the war made any difference at all?

Not at all… (fades out)

Robert Bowman, CBC Radio, interviewing François Latry in: London After Dark. CBS Radio. Recorded 24 August 1940. 4:45 to 8:45. Audio clip found at: Widner, James F. Radio Days. http://www.otr.com/londonafterdark.shtml. Link valid as of August 2019.

LONDON— (U.P.) —Rotund Francis Latry, London’s best known chef and czar of the kitchens at the swank Savoy hotel, has more food shopping difficulties than any British housewife but said today he actually is looking forward to solving the problem of the reduced rations which went into effect today. “It will test my ingenuity,” he said, chuckling. “I remember things now taught me when I was a kid in France. My mother used to teach me to use every last bit of everything. I am doing just that now.”

He said rationing already had forced him to remove virtually all beef and lamb dishes from the hotel’s “daily specials,” the choice of almost 90 per cent of diners. Beef and lamb are still available a la carte and for the daily specials he substitutes chicken, turkey, duck, and other unrationed meat.

Latry takes special pride in dishes he has evolved using unrationed ingredients. For instance there is “chausson de fruits de mer” which consists of a baked potato skin stuffed with mussels, scallops, soft roe or herring and other shellfish. “And we do not waste the inside of the potato,” he said. “We serve that with the chicken course.”

He is also proud of a soup he makes of fish heads, formerly not used.

In preparing most meats, Latry now uses cuts formerly spurned by the Savoy kitchen. Before the war the hotel could buy just the cuts wanted; now they must take the whole carcass. “Even when serving chicken we are popularizing parts which seldom satisfied our customers before the war,” he boasted. “They used to like only the breast and wings of chicken. Now I have prepared tournedos made from the leg of chicken and people seem to like them. In my opinion the legs are the best part of a chicken anyway.”

The increased use of vegetables also serves to mitigate the shortage of meat, according to Latry. Cauliflower, parsnips, turnips, beets, carrots, and potatoes are plentiful. “I make up 50 dishes from potatoes alone,” Latry said.

But like British housewives, Latry encounters extreme difficulty in obtaining the lowly onion. Tomatoes, formerly imported from France and the Channel islands, no longer are available at all.

Most fruits, except oranges and a few home-grown, apples, have disappeared from the markets Bananas, pears, and other fruits no longer are imported, even in cans, because shipping space is needed for more important commodities.

Latry makes an “ice cream” which doesn’t contain cream or milk. He says the customers swear they cannot tell the difference from real ice cream. How does he do it?

“That’s my secret,” he smiled.” [18]New Rations Challenge London’s Best Chef. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: Wisconsin State Journal. 7 January 1941. Page 18.

François Latry and Grouse

Latry continued the Savoy’s tradition of being one of the very first hotels in London each year to offer grouse on the menu after the annual start of grouse season on 12th August.

He believed in cooking and serving grouse absolutely simply:

‘The most beautiful and delicious grouse,’ [Latry said], ‘is the grouse that is roasted plainly. Put the bird in the earthenware dish and put some rich brown sauce on its breast, as well as a little in the dish. The oven should be fairly hot. The only way to tell if the bird is cooked is to tilt the dish. The moment that the brown gravy ceases to drip from the bird it is exactly cooked. That is the secret. It should be served very hot.’ M. Latry also adds a few words on choosing the most suitable grouse. ‘The perfect grouse’, he says, ‘may be either a male or female bird, but it must be small boned and weighty. The limbs should not be too large, and most of the weight should be in the body. The great point to ensure is that it has not been shot through the breast.’

‘With the grouse only one vegetable should be served — potatoes; these should be chip potatoes done to a nice brown. No other vegetable is necessary; a little bread sauce should be served, to be had if desired. With chips and bread sauce, the flavour of a perfectly cooked grouse can be appreciated to the full. It is the dish of the year.'” — The Brown, Delicious Grouse: Some New Recipes. The Montrose Review. 13 August 1926. Page 8, Col. 1.

François Latry and Coffee

“French men and women know that the best way of making coffee is the simplest way. Throughout France coffee beans are roasted in a frying-pan over a charcoal fire. There is an art in roasting coffee — half a second too long and the beans are spoiled. The test is to watch when the beans begin to ‘sweat’ — i.e., when the oil begins to ooze out. Then is the time to shake up the beans quickly to get the flakes off and to ventilate them. It is important for each blend of beans to be roasted separately, as each will require different lengths of time roasting. When nearly cold, grind the beans — every French house has its own moulin café or coffee-grinder. Coffee should only be made in an earthenware pot equipped with a filter. After heating the pot thoroughly, put in the filter coffee in the quantity of one tablespoonful for the pot and one for each person. Using water that has just been brought to the boil, pour on two tablespoonfuls of water very slowly. Put the lid on the filter for two minutes, then slowly pour on the balance of the water. Take out the filter, and from the coffee just made pour two tablespoonfuls again through the filter. Serve immediately: coffee must not wait for you.” — M. François Latry, Maitre-Chef des Cuisines, Savoy Restaurant. To the Editor of the Times. Good Coffee. The Times. London. 4 January 1938. Page 8.

François Latry on Copyrighting Recipes

“I think more fortunes would have been lost than made if dishes were copyright,” said M. F. Latry, head chef at the Savoy Hotel, Strand, W.C, yesterday to a Daily Mail reporter. M. Latry was discussing the views, reported in The Daily Mail yesterday, of M. Lespinasse, of the Paris restaurant L’Escargot, who thought that ordinary dishes could not be copyrighted but that pastries and sweets could. “If a dish were copyright,” said M. Latry, “the probability is that it would never be heard of outside the hotel or restaurant in which it was sold. Take the case of M. Escoffier, who invented Peche Melba. His name is known all over the world as the inventor of that famous sweet. It might be argued that if he had secured a copyright for it he might have made a fortune; on the other hand, it is more than likely that had a copyright been secured Peche Melba would never have been known outside the hotel in which it was invented.” — Patent Puddings. London Daily Mail. London, England. 9 June 1922. Page 5.

François Latry and the Nutritional Value of French Cuisine

In a 1928 letter to the Times, he maintains that French cuisine is founded on “scientific principles” and therefore has good nutrition built into it:

Sir, I have read with the greatest interest the article by your Medical Correspondent, “New Light on Vitamins”, in The Times today. I am in entire agreement with the quotation to the effect that Vitamin A is not found in sufficient quantities in the ordinary diet, and this I believe to be the case to a greater extent with the average British menus than with those of any other country. Might I add a word or two on this matter, seeing that the subject of food values, while not generally understood by us in such medical terms, has been the subject of great study in the haute cuisine for over two centuries? Might I be permitted to express the opinion, therefore, that I think the growing popularity of the French cuisine in this country is a a very excellent thing, not only in stimulating the artistic sense of the palate, but for medical reasons as well? It was known to our chefs 150 years ago, for instance, that the liver oils of certain fish and the liver fats of sheep, calves and certain poultry possessed great virtues — perhaps the exact nature of these virtues was not known — and it would be difficult to find a menu not at least moderately rich in such oils and fats, and consequently in the all-important Vitamin A, as we know it to-day. I think it might be claimed, indeed, that the French cuisine has been built up on scientific as well as on appetizing and artistic principles, and it has become an unconscious part of the French chef’s training and art to consider food values as well as food flavours. As I say, this has been in process of development for the last 200 years, or possibly longer. The oldest histories of the cuisine show evidence to this effect. Of course, the actual word ‘Vitamin’ has been absent from their vocabulary, but at the same time they have always had prominently in their minds the necessity of maintaining a correct balance of nourishment with the material at their disposal. Yours faithfully, François Latry, Maitre des Cuisines, Savoy Restaurant, WC2, Oct. 23.” [19]To the Editor of the Times. Old Light on Vitamins. The Times. London. 26 October 1928. Page 17.

Popular Science Magazine in the States picked up his assertions about vitamins in French cuisine:

“And now comes Monsieur Francois Latry, famous chef of the Savoy Restaurant in London, and tells us that the French chefs of 150 and 200 years ago knew the value of vitamins without knowing them by name. They would not have recognized Vitamin-A (the rickets-preventing element found, for example, in cod liver oil) even if they had stumbled over it, but it would be difficult to find one of their menus, says Monsieur Latry, that was not at least moderately rich in the liver oils of certain fish and the liver fats of sheep, calves and poultry.” [20]Popular Science Monthly Magazine. Bonnier Corporation. September 1930. Vol. 117, No. 8. Page 68.

François Latry and Christmas

For Christmas 1926, he decided to break the mould on the Christmas menu he had been offering, and instead offer one that featured the favourite dishes of well-known historical figures. This was considered radical enough to be newsworthy over in the United States:

“Francois Latry, genial chef of the Savoy hotel, master of the mixing spoon and baking oven, scholar and food artist, has rebelled against the orthodox Christmas dinners he has been designing for the past twenty years.

Instead of the traditional turkey and plum pudding, he has prepared a Christmas menu of historical significance including the choice viands of Cardinal Richelieu, Queen Elizabeth, Henry IV, King John (the first English gourmet) and Catherine de Medici.

“The Christmas dinner, like nothing else in the world, must be a thing of imagination, sentiment and perhaps a little mystery,” Latry said earnestly, in his kitchen. “No meal in the world has had such a history as our Christmas dinner. Why not offer a meal, every dish of which used to be the favorite Christmas delicacy of great historical figures?”

He produced his menu. It read: Le Pot Henry IV; Les Filets de Sole Richelieu; Le Dindonneau a l’Anglaise a la Reine Elizabeth: Cranberry Sauce: Les Petits Choux aux Marrons; Christmas Pudding flambe Joyeaux: Dorta [sic] Fiorentina de Catherine de Medici: Le Mousse au Clicquot; Les Gourmandises du Pere Noel.”

“The soup has a history going back to the battlefield of Arnay-le-duc, where Henry IV distinguished himself In 1569,” he explained. “It was first made by King Henry’s soldiers on the battlefield under his instructions. Simple, it is made from capon flesh and is flavored with rice and tomatoes.

The sole was one of Cardinal Richelieu’s favorite dishes. The filets of sole, after being buttered, are braised in white wine for about 12 minutes over a slow fire, with pepper and salt. A sauce is made of fish stock, white wine and butter, boiled to the consistency of syrup, and it should be poured through a muslin before use. An additional garniture of green marenne oysters completes the delicacy.

Latry’s attention was called to the turkey which he had included on the menu. “Ah,” said Latry, “that, alas, is a concession to those conservatives who would insist on its presence. But it is made according to an old recipe originated in 1573 when turkey became an English dish. In those days it was stuffed with sausage meat and bread crumbs and it is still the best way to serve turkey.”

Catherine de Medici’s favorite sweet is made similar to our Christmas pudding, with all kinds of fruits, highly spiced and boiled to a dark rich mixture. Catherine made it peculiarly her own by covering the whole with almond paste, laying the mixture in the paste like a tart.” [21]Associated Press. From Historic Figures Comes Today’s Menu. Kokomo, Indiana, USA: Kokomo Tribune. 25 December 1926. Page 5. [Ed: perhaps best to take Latry’s historical accuracy with a grain of salt.]

In 1926, he gave out his recipe for Christmas puddings:

“…Francois Latry, chef of the Savoy restaurant, already has made 200 pounds of Christmas pudding for consumption in the United States. No ritual could be more impressive to the epicure than to see Mr. Latry mix his first plum pudding of the season.

For thirty years he has assembled his assistants about him several weeks before Christmas. Then, with a flourish that might be taken from some quaint, religious ceremony, he has poured the first bottle of brandy into the pudding mixture. A diminutive page boy always makes the first stir.

Here is his own recipe for seven-pound English plum pudding, made public for the first time:

Ingredients: Twelve ounces malaga raisins, 12 ounces currants, 12 ounces suet, 9 ounces flour, 4 ounces chopped, apple, one ounce orange peel, 8 ounces brown sugar, half pint milk, 12 ounces Smyrna raisins, 12 ounces crystallized peel, 10 ounces bread crumbs, one ounce ginger, one ounce citron peel, one teaspoonful salt, six eggs, quarter of a pint of brandy or sherry.

How to make it: All the dry ingredients should be well mixed together. A little extra mixing well repays the trouble. Beat the eggs and add them to the milk, then pour over the dry ingredients and again mix thoroughly. Pack into greased moulds and boil for six hours at the time of making. The puddings should be boiled for a further six hours when wanted for use.

The best sauces are white, custard or brandy sauce.” — Associated Press. Brandy Needed to Make This Plum Pudding: Famous Chef Gives Recipe for Traditional Christmas Delicacy. In: Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. 8 November 1926. Page 14.

In 1926, Latry gave the following advice on what to do with Christmas dinner leftovers:

“The problem of providing appetizing meals on the two or three days after Christmas is, to my mind, even more trying to the average hostess than the preparation of the Christmas dinner itself, people are apt to be more fastidious on the day after Christmas than on Christmas day — generally because they have been too generously fed the day before.

Turkey and geese that prove too big and Christmas puddings that were too rich — the remains of these will want to be disposed of, and while, strictly speaking, they should not be allowed to put in an appearance at all so soon after the festal day, they can be disguised so as to reappear like entirely new dishes, and extremely delicious as well.

This is what I suggest be done with the turkey that has been good service on Christmas day. The remains of the turkey should be made into “ailerons de dindonneau dores.” This is made by slightly coloring the remaining joints in a saute pan, or any shallow sauce pan, and in the same butter afterwards gently brown a sliced carrot and onion, parsley stalks, thyme and bay. Put the turkey back among the aromatics and cook in a very slow oven.

Then, take out the remains of the turkey, make a stock of the cooking butter, in which the turkey should be boiled 15 minutes.

My suggestion is, don’t tell your guests that it is turkey, but let them think it is a surprise dish and leave them to guess. I doubt if they will guess correctly.

It is a mistake to produce plum pudding again in its original form. For one thing, cold plum pudding is apt to be indigestible and flat.

Take the remains and cut them into slices. Arrange them on a buttered dish, powder with sugar, sprinkle with brandy or rum, put with another dish [Ed: sic] and warm slowly in an oven for about 20 minutes. Your guests will realize it is the Christmas pudding but they will enjoy it quite as much as they did the day before.” — Latry, Francois. Meal Following Christmas is Hard to Prepare: London Chef Tells of Methods of Handling the Sunday Meals Following Christmas. Oelwein, Iowa, USA: The Oelwein Daily Register. 21 December 1926. Page 1.

In 1928, Latry made Christmas Puddings to be shipped to the United States, but owing to prohibition there, first had to clear with U.S. customs that the puddings would be allowed into the country, as they were doused heavily in alcohol:

“We don’t know how many people in Sheboygan, or for that matter in the country at large, received a circular from St John Wright, 10 Essex Street, London, the day before Christmas telling how 730 gallons of liquor had arrived in the port of New York and was going to play a part in the holiday festivities and without any interference from the prohibition department.

As we scan the circular there is much of interest even in this dry country of ours, and as we continue to read each paragraph we get brimful of information. After telling about how the liquor got through the customs house without a cent of duty we learned that this 730 gallons was concealed in some 5,600 plum puddings that had been made by the chef of the Savoy hotel, London, and were to be consumed in the United States.

A conversation something like the following is purported to have taken place between Chef Latry and the customs department of the United States treasury in London:

“Your people want me to send Christmas puddings to your country,” he said. “If I make them ‘dry’ they won’t keep. If I souse them, as Christmas puddings should be soused, you’ll confiscate them,— or won’t you?”

The officials pondered over it for a while, then sent Latry this message:

“Plum puddings, or confectionery that contain wine or spirit as a flavouring, are not regarded as an infringement of the prohibition law. Your puddings, we take it, will not contain liquor in liquid form, and there will not, therefore, be any difficulty in admitting them to the United States.”

After the conversation, according to the circular, Latry mixed his puddings and injected spirits in order that there might be good feeling among the cookies and those who were going to eat the puddings. We are not going to try to give you the whole recipe, but each pudding is supposed to contain one-half pint of brandy and one-half pint of stout, and in order to make it more inviting, the chef announces that all of the fruit was soaked in brandy for several days.” [22]Now They Eat Whiskey, What Next? The Sheboygan Press. Sheboygan, Wisconsin, USA. 28 December 1928. Page 14.

François Latry and Haggis

In 1922, Latry invited the press in to photograph him making haggis for Robbie Burns Day.

In 1935, he gave out his recipe for haggis:

“The old gentleman [Aristophanes] mentioned the dish [haggis] in “The Clouds”, written in 423 BC.

I asked M. Francois Latry, the famous chef of the Savoy Hotel, who had made this startling discovery, to tell me some more about it all, writes a special correspondent in the Sunday Dispatch.

For M. Latry, besides being a chef, is an authority on the history of his art and can whip out the answers to such conundrums as “Who devilled the first kidney — and where?”

Haggis, he assured me, was first produced by the ancient Greeks, whose civilisation thus has one more thing to answer for.

In 1589 it was introduced into the French Court by Henry IV, and was known as “hachis.”

French soldiers for many generations were particularly fond of it, and haggis was frequently carried forward to battle by the battalion cooks.

M. Latry has written his own recipe for haggis:

Take the heart, lungs, and liver of a sheep, boil together for half-an-hour. Take away the meat and chop it very finely, except part of the liver, which, after cooling, must be grated.

Spread the chopped mixture on the table and season with salt, pepper, nutmeg, Cayenne pepper, and chopped onion.

Add the grated liver, ¼ lb. oatmeal, and 1 lb. chopped beef suet. Place the mixture in its case, allowing enough room for the meat to expand while cooking.

Add a glass of good stock, pricking the case all over with a needle, and sew up the opening. Boil it for three hours.

Serve very hot, with potatoes purée and a dash of old whisky.” — Greeks had two words for haggis: Koila Probateia. The Straits Times, 15 December 1935, Page 43.

François Latry and Lent

In 1927, he observed a Good Friday tradition among sharing with fellow chefs a hot-cross bun and a glass of wine:

“More than 200 chefs entered the rooms of M. Francois Latry, chef of the Savoy Restaurant, London, and ate a small hot-cross bun and drank a glass of wine. This was the only break, itself an old custom among chefs in France, which they observe every Good Friday.” — Tantalized Chefs. The Straits Times, 21 May 1927, Page 11

In 1933, he proposed that London commemorate Marie-Antoine Carême on the upcoming Shrove Tuesday with appropriate pancakes:

“Sir, Your readers are no doubt aware that Paris is at present celebrating the centenary of the great Antonin Carême, chef to Talleyrand and a founder of the haute cuisine. It occurred to me that Shrove Tuesday — important to gourmets as being the last day before the Lenten fast — might be an appropriate occasion to honour Carême in London, by serving such dishes as Pâte de Saumon à la Carême and Crêpe du Mardi Gras Carême — the latter being Shrove Tuesday pancakes that that notable sauce. Carême prepared pancakes in the usual way but he stuffed them with a butter-sauce, strongly flavoured with kirsch. The pancakes are then sprinkled with icing sugar and passed under a toaster to glaze. Before serving they should be sprinkled with kirsch and lighted. Both these recipes are taken from Carême’s ‘L’Art de la Cuisine Française,’ of which great work I am fortunate enough to possess a copy. It was bequeathed to me by one of Carême’s disciples – M. Coulette. Yours respectfully, François Latry, Maitre des Cuisines, Savoy Restaurant.” [23]To the Editor of the Times. Pancakes a la Carême. The Times. London. 28 February 1933. Page 15.

In 1934, he proposed that English cooks should draw more on salted cod for meals during Lent:

“Sir, In this time of lent the problem of choosing interesting, yet appropriately Lenten, dishes presents itself in many households. May I therefore draw your readers’ attention to the Lenten food which both in France and Italy is the most popular and traditional of all — la morue (salted codfish)? The English housewife tends to ignore this excellent and economical fish, possibly because she does not know some of the more appetizing methods of its preparation. Soufflé de morue is a dish favoured for many centuries in the Savoie country. For this 1 lb of the freshly boiled and flaked fish is made into a paste with two tablespoonfuls of thick béchamel sauce. Season the paste and heat in a saucepan, adding the yolks of three eggs and four whites beaten to a stiff froth. Then place in a buttered saucepan and cook and serve as for a soufflé. When served in this way, or garnished with egg or vegetable sauces, la morue ceases to merit such epithets as ‘dull’ or ‘tasteless’, which are often applied to cod in this country.” — Yours respectfully, François Latry, Maitre des Cuisines, Savoy Restaurant” — To the Editor of the Times. Lenten Dishes. The Times. London. 28 February 1934. Page 10.

François Latry and American Thanksgiving

In preparation for American Thanksgiving in 1932, Latry shared his recipe for pumpkin pie with readers of the Times of London:

“I have read with great interest the letters appearing in your columns relating to the pumpkin. I venture to think that your readers might like to know the traditional method which I use to prepare pumpkin pie for the Thanksgiving Day banquets of the American Society in London. The skin and pips are removed from a ripe pumpkin, which is then cut into cubes and boiled. I then add cream, caster sugar, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, the yolks of eggs and a tablespoon of brandy. The mixture is then placed in a tin lined with pastry and baked in a moderate oven. The result is a piquant and delicious dish, which deserves far greater popularity in England than at present.” [24]François Latry to the Times of London. 27 September 1932. Quoted by: Dupleix, Jill. Sweet pumpkin pie: Time to squash the pumpkin’s raw deal. London: The Times. 29 October 2004.

References

| ↑1 | De Cordova, R. Thumbnail interviews with the great: Genuis en casserole. London, England: The Sphere. Saturday, 16 October 1926. Page 118, Col. 3. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | De Cordova, R. Thumbnail interviews with the great: Genuis en casserole. |

| ↑3 | “M. Latry was born in Gex (Ain), France, and received his first cooking lessons at the age of 10 from his mother, herself a cook of note. An apprenticeship begun at 14 took him through ten years of training in the best hotels of Lyons and Paris.” In: “Chef to Sovereigns quits London Post.” New York Times. 11 March 1942. |

| ↑4 | De Cordova, R. Thumbnail interviews with the great: Genuis en casserole. |

| ↑5 | London Makes Merry: Amazing Scenes in Hotels and Streets. Nottingham, England: Nottingham Evening Post. Monday, 1 January 1923. Page 1, Col. 2. |

| ↑6 | Church, David M. INS Staff Correspondent. Daily NewsLetter: General News and Gossip from Staff Writers at Home and Abroad. In: The Oxnard Daily Courier. Oxnard, California, USA. 9 January 1925. Page 2. |

| ↑7 | In the Spotlight of Today’s News. Waterloo Evening Courier. Waterloo, Iowa, USA. 16 June 1927. Page 1. |

| ↑8 | US Bids and London Chefs. Charleston Gazette. Charleston, West Virginia, USA. 22 July 1928. Page 7. |

| ↑9 | Société des Grands Hôtels de la route Paris-Nice, Article 75, III. In: le Memorial d’Aix. Aix-en-provence. 13 juillet 1932. Page 4. |

| ↑10 | Cooks Go On Diet to Do Their Work Better. New Castle News. New Castle, Pennsylvania, USA. 5 April 1929. Page 28. |

| ↑11 | Children Now May Dine on Imitation Delicacies. Chronicle Telegram. Elyria, Ohio, USA. 2 August 1929. Page 12. |

| ↑12 | National Museums Liverpool, Maritime Archives and Library. B/CUN/3/7/3/1 14 Nov 1936 – 30 Sept 1940. |

| ↑13 | Beebe, Lucius. This New York. Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California, USA. 9 October 1938. Page 2-A. |

| ↑14 | Dale Harrison’s New York. Printed in: Press-Citizen. Iowa City, Iowa, USA. 4 November 1938. Page 11. |

| ↑15 | Chef to Sovereigns Quits London Post; Francois Latry of Hotel Savoy Retires Because of Health. New York Times. 1942. |

| ↑16 | Woolton pie creator dies. The Times, London. Wednesday, 17 August 1966. Page 1. |

| ↑17 | Études Drômoises. Revue du patrimoine Drômois. Montélimar : différents articles. Au relais de l’Empereur, Par J. Delatour – N°1 de 1999 p. 20 à 25. Retrieved April 2011 from http://etudesdromoises.free.fr/pages/pages_revue/resumes_d_articles/special_montelimar.htm |

| ↑18 | New Rations Challenge London’s Best Chef. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: Wisconsin State Journal. 7 January 1941. Page 18. |

| ↑19 | To the Editor of the Times. Old Light on Vitamins. The Times. London. 26 October 1928. Page 17. |

| ↑20 | Popular Science Monthly Magazine. Bonnier Corporation. September 1930. Vol. 117, No. 8. Page 68. |

| ↑21 | Associated Press. From Historic Figures Comes Today’s Menu. Kokomo, Indiana, USA: Kokomo Tribune. 25 December 1926. Page 5. [Ed: perhaps best to take Latry’s historical accuracy with a grain of salt.] |

| ↑22 | Now They Eat Whiskey, What Next? The Sheboygan Press. Sheboygan, Wisconsin, USA. 28 December 1928. Page 14. |

| ↑23 | To the Editor of the Times. Pancakes a la Carême. The Times. London. 28 February 1933. Page 15. |

| ↑24 | François Latry to the Times of London. 27 September 1932. Quoted by: Dupleix, Jill. Sweet pumpkin pie: Time to squash the pumpkin’s raw deal. London: The Times. 29 October 2004. |