Jenia Nebolsina/ Pixabay.com / 2015 / CC0 1.0

The 1st of January is New Year’s Day around the world.

Some foods are seen as lucky to eat at New Year. The foods, though, vary by culture:

- Austria: pork;

- Brazil and Italy: lentils;

- Denmark: boiled cod;

- Dutch: doughnuts (Oliebollen);

- Germany: pig-shaped items;

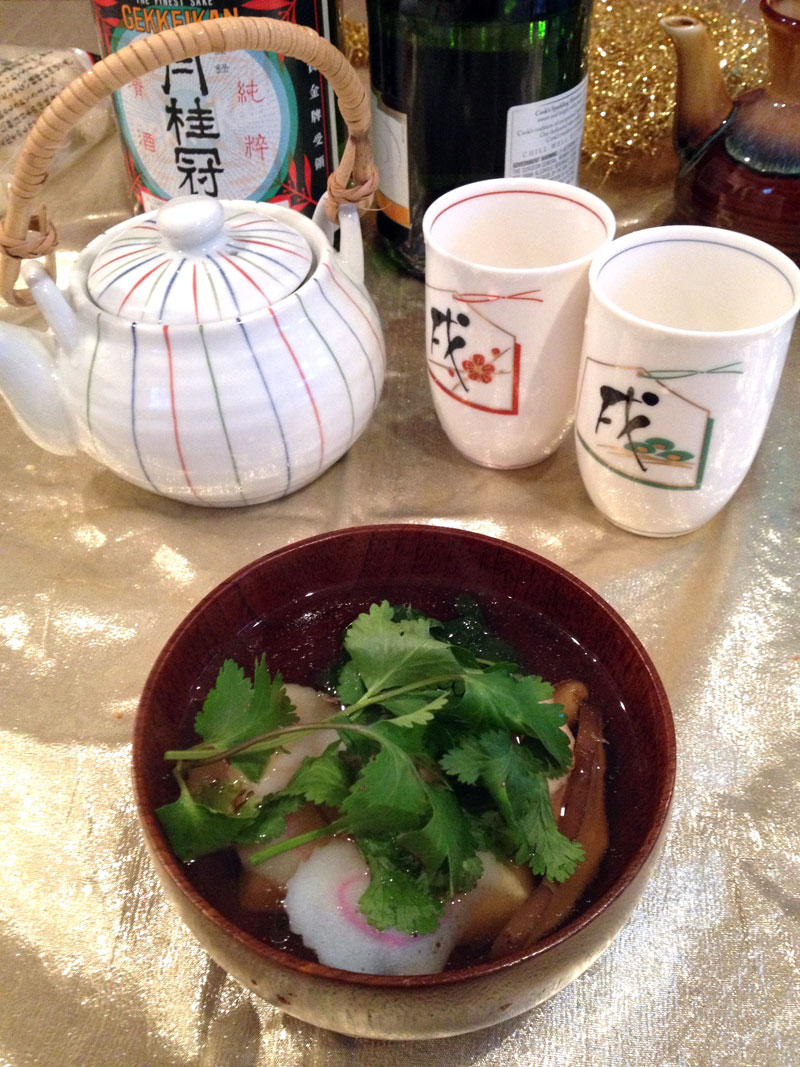

- Japan: Ozoni;

- Southern US: black-eyed peas;

- Spain, Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela: 12 grapes at midnight, one for each of the upcoming months;

- Pennsylvania: sauerkraut.

Most North Americans, in both Canada and in the U.S., would traditionally watch some of the celebrations in Times Square, New York on television, if only briefly while channel surfing. This may have changed in recent years as TV habits changed.

#NewYearsDay

See also: Hogmanay

Germany

In Germany, New Year’s Eve is called “Silvester”; New Year’s Day is called “Neujahrstag”.

Germans will give each other a “luck bringer” (“Glücksbringer”). One of the most popular “luck-bringers” is a “lucky pig”, called a “Glücksschwein”. In German, to “have a pig” (“schwein haben”) means “to be lucky.” In decks of cards, the Ace is know as “die Sau”, the sow, a female pig.

Instead of giving people actual pigs, however, today people will give pigs made from marzipan or pastry.

German marzipan pig. Bernadette Wurzinger / Pixabay.com / 2016 / CC0 1.0

New Year in Japan

In Japan, New Year is called either “Shogatsu” or “Genjitsu”, and celebrated on the 1st of January, as it is in the West, though the big celebrations are held on New Year’s Day, not the evening before. In fact, many people go to bed early on the 31st December, so they can wake before sunrise on the 1st of January.

Before New Year, houses in Japan must be completely cleaned, and people send New Year’s greeting cards (though many now send them as E-Cards instead of by post.)

Traditional clothing is worn on New Year’s Morning. Buddhist temples toll their bells 108 times.

Shrine in Kyoto, Japan. vivi14216 / wikimedia / 2014 / [Public Domain]

The celebrations go on until 3 January, with lots of visiting.

Ozoni soup with rice cake. Gry / Pixabay.com / 2013 / CC0 1.0

History Notes

In many older calendars, the start of a new year was actually celebrated in spring, tying it into the rhythms of the earth. If you think about it, 1 January is purely arbitrary and not really connected to anything, but it was the Romans who changed it for us.

The Romans at first observed New Year in spring. The Roman calendar got out of whack over time, both because time was being lost, and because of political tampering. In 153 BC, the Roman Senate approved a re-ordering of the calendar, fixing 1 January as the New Year. That date was reinforced with the Julian calendar passed in 46 BC.

During the Middle Ages, the concept of a New Year’s Day was moved back to the spring by the Church, and fixed on the 25th of March, Lady Day — the annunciation, when the Angel Gabriel told Mary she was with child. This made it 9 months (39 weeks and 2 days to be precise) until the 25th of December, Christmas Day. Still, the Church remained opposed to any New Year’s celebrations until around 1600 AD.

Lady Day became the first of four “quarter days” dividing the year (marking the four quarters of the year), and thus was the fiscal beginning of the year. That’s why around that time of year many income taxes are still due and many government fiscal years end, etc.

Eventually, though, everyone just found it easier eventually to count the New Year as starting from the start of the calendar year, the 1st of January. Many in England and Wales had already been celebrating the 1st of January as part of the Yule celebrations. The trend accelerated after the western European calendar change of 1752.

In California, the New Year’s Tournament of Roses Parade was first held in 1886.

The ball-dropping in Times Square, New York, started in 1908.

New Year used to be a time of very heavy drinking, and is still seen that way in North America and Europe, though tough drunk driving laws that have come into effect have mitigated that somewhat.

Literature & Lore

Superstition in the Ozarks held that taking anything out of your house on New Year’s Day would mean a year of want in the house:

“Perhaps the most striking feature of the Ozarkers’ New Year’s behavior is their reluctance to allow anything to be taken out of the house on January 1. I once knew a woman who absent-mindedly carried a bucket of ashes out on New Year’s morning; she was shaken almost to the point of hysteria, and the whole family was horrified, although nobody seemed to know just what specific calamity was supposed to result.

Many broad-minded modernists pretend that there is no harm in carrying something out, provided you are careful to take something else in; thus it’s permissible to throw out a pan of potato peelings if one immediately lugs in a bucket of water or an armload of wood. The real old-timers figure it is safer not to carry anything out of the cabin on January 1, but to pack in as much stuff as possible. Some old folks take this so seriously that they will not allow anyone to enter on that day without depositing something, even if it is only a few walnuts or a handful of chips. This precaution, according to the old tradition, insures a whole year of plenty for the people who live in that house. ‘It ain’t much trouble, just for one day,’ an old man said as he insisted that I get a stick from the woodpile before coming into his shanty, ‘an’ me an’ Maw don’t aim to take no chances.'” — Randolph, Vance. Ozark Superstitions. Columbia University Press, 1947. Chapter 4.

Language Notes

Most people commonly say “Happy New Year’s!” when in fact what they mean is “Happy New Year!” There is no reason for “Year’s” to be possessive.

The correct expression in English is either Happy New Year, Happy New Year’s Eve or Happy New Year’s Day — but not Happy New Year’s.

Cafe in Spain at New Year, wishing tourists a Happy New Year. Biancaritter1 / wikimedia / 2014 / [Public Domain]