Beef counter at Dittmer’s, Los Altos, California. Phil Denton / flickr / 2013 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Beef is the flesh from cattle, either male or female.

Modern consumers tend to think of only more choice cuts of the animal as being “beef”, but technically even beef fat, and offal such as liver, tongue, tripe, etc., count as beef.

A castrated bull is called a steer; a virgin cow is called a heifer. Meat from young cattle is classed as veal.

- 1 Grass-fed versus corn-fed beef

- 2 Aging Beef

- 3 Dry aging

- 4 Wet Aging

- 5 Butchers’ choices

- 6 French Beef

- 7 The future of beef

- 8 Beef production and supply

- 9 Beef cut terminology is confusing

- 10 Beef Charts

- 11 Choosing Beef

- 12 Internal temperature reference charts for cooking beef

- 13 Storage

- 14 History Notes

- 15 Literature & Lore

- 16 Sources

- 17 Related entries

Grass-fed versus corn-fed beef

A cow’s natural diet would be grass. Traditionally, all cows were let graze for grass and other greens. In Britain and France, grass-fed is still the norm. In North America, farmers discovered that feeding cattle grain allowed the cows to be weight-ready for market earlier, and so corn-fed became the norm. Corn-fed cattle require can require nutritional supplements to supply the nutritional elements that grass otherwise would, in order to help ward off infections and diseases. (This is not to say that grass-fed cattle might not receive the same types of supplements as well.) And growing the corn itself to feed the cattle has an environmental impact, grass-fed fans argue.

In the UK, corn-fed beef is more expensive, because it’s imported: the home-grown stuff is grass-fed. In North America, it’s the opposite: it’s the corn-fed beef that is cheaper.

Many people swear there are important differences between prime beef cuts from corn-fed beef, vs grass-fed beef; that corn-fed has more of a silken texture to it and more marbling, while grass-fed has more chew and a more complex range of flavours to it. Some say that grass-fed is superior in many ways (including politically and morally.) Others such as Chef Harold Dieterle of the critically-acclaimed Perilla restaurant in New York say that the claims of the grass-fed camp are “1,000 percent bogus.” [1]Hesser, Amanda. Recipe Redux: Rib Roast of Beef, 1966. New York Times. 26 January 2011.

Aging Beef

To call a spade a space, aging is the controlled start of the natural decomposition process of the meat. Beef is aged to tenderize it and develop flavour. During aging, enzymes naturally present in the meat break down some muscle fibre. Many authorities say that most of the benefits of aging occur in the first week or week and a half and that after that, the increase in benefit slows dramatically. It’s not entirely clear that we should take this entirely at face value, as some beef aficionados and very high-end butchers seem to age for up to 6 weeks, and it’s pretty obvious that the week and a half figure coincidentally gets the meat to the store faster for faster sale.

Dry aging

To dry age beef, the meat is hung without packaging or covering in chillers at a controlled temperature range of 0 to 1 C (32 – 34 F .) The humidity is also strictly controlled. Too much moisture would obviously simply cause the meat to spoil; too little would dry the meat out and encourage excess “shrinkage.” The shrinkage is caused by the meat losing moisture as it ages. As the moisture evaporates, it concentrates the juices in the beef improving the flavour. All of this sounds good to us as a consumer, but to a seller this is bad, especially as shrinkage can be anywhere from 5 to 20% of the weight, which of course leaves less water in the meat to tip the scales when it comes to pricing.

Dry-aged meat is dense, taut and dark-rose coloured. You can tell it’s been dry aged if it almost bounces a little when you slap a piece of it onto a cutting board.

Most dry aging these days is done by high-end butchers, and reserved for the best cuts that will command a premium price to help compensate for both the lost weight and the storage costs. In an interesting development, though, Sainsbury’s in England reintroduced dry-aged beef in 2003 to its meat counters under the product name of “Taste The Difference 21-day aged beef”. The product was still being carried as of 2020. [2]”Last year, Oliver backed the launch of Taste The Difference 21-day aged beef, which was one of the most popular products launched by Sainsbury’s in 2003 and now accounts for nearly 10% of beef sales.” Whitehead, Jennifer. Jamie Oliver signs for another year with Sainsbury’s. Campaign Live. London: Haymarket Media Group Ltd. 10 May 2004. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/jamie-oliver-signs-year-sainsburys/210453

British steak fans seem more likely than Americans to want to ensure that their beef has been dry-aged. “It can be argued that only the very best dry-aged (where the beef is hung in a cool room to develop flavour) USDA corn-fed steaks have a decent flavour. The cheaper versions have all the depth of a muddy puddle.” [3]Parker Bowles, Tom. Holy cow! How to choose the perfect steak. London: Daily Mail. 14 September 2009.

Wet Aging

To wet age beef, the meat is vacuum sealed in packaging called Cryovac®. The vacuum seal means that humidity control is not needed, which means that the meat can be shipped right away, under refrigerated conditions of 0 to 1 C (32 – 34 F), letting the aging take place during shipping. Cryovaced beef and lamb from New Zealand is now routinely shipped to North America, having wet aged 55 to 60 days. As it was never frozen, it can still be sold as fresh. This is one obvious advantage for sellers.

The second big advantage is that because that meat is in a vacuum sealed bag, it’s going to be pretty hard for much evaporation to take place which would result in shrinkage (or concentration of flavour, for that matter.) Shrinkage losses with Cryovaced beef are a minimal 1 to 2%. The moisture that does run off, which is called “purge”, is drained away when the bag is opened. The bag gives off a bit of an off-smell when it’s first cut open, but that quickly goes away.

Wet-aged meat will be a brighter red than dry-aged meat. When you slap it onto a cutting board, it will impact like a wet sponge, and probably splatter a little. Barbeque enthusiasts say they notice the high moisture content in wet aged beef, and that their steaks essentially just steam on the grill, instead of barbequing. But chances are that any beef you buy nowadays from a regular store is wet aged. Even if the store’s butcher seems to be cutting pieces from large hunks or sides of beef, chances are those large hunks were Cryovaced, and the only aging they saw was inside a wet plastic bag for the amount of time it took the truck to drive to the store.

Despite the term “wet aging”, no water is actually added to the bag before sealing.

Butchers’ choices

Butchers aren’t paid any more than we are, so they have to stretch their grocery dollars, too. Since meat is their business, it makes sense to pay attention to what they buy for themselves, which isn’t always necessarily the same thing as what the store wants them to recommend to you over the counter.

Among a butcher’s top three choices are Porterhouse Steak, Top Sirloin Steak and Hanger Steak.

French Beef

French beef (like Scottish beef) is mostly fed on grass (North American beef is grain fed.) In general, French beef will be tougher than North American meat and with less marbling, and less juicy when cooked. The French breed their cattle to produce both meat and milk. The French only age their beef 3 to 5 days.

The future of beef

Producers and retailers are now looking for ways to increase sales on the tougher cuts, as those cuts show the most room for price growth. Just two tough sections alone, the Round and the Chuck, make up 53% of the cow by weight, so you can understand why they’d want to see price growth on cuts from these areas. Ending labelling confusion at the meat counter would be an important first step in this.

Lower fat has become a mania, and beef farmers have put their cattle on diets. This produces meat with less marbling, which will dry out more easily during cooking. You need to take this into account when cooking beef, especially when using cooking times from older recipes which presumed fuller marbling. Some cooks point out, however, that you sadly can’t do much to make up for the flavouring that was lost along with the more generous marbling of yore.

Beef production and supply

The beef production sector requires a long lead time to get beef to market. It can’t pivot on a dime, so it has to try to predict consumer tastes and demands four to five years ahead:

“At the start of the beef chain, the suckler herd (the breeding stock for beef bred cattle, i.e. cattle that are destined for the beef market), produce approximately 1 calf every 12 months. The gestation period is approximately 283 days (roughly 40 weeks, similar to humans!). Once the calf is born it will grow for the next 24 to 36 months (depending on sex and breed) until it reaches the ideal weight for slaughter. If we take into account gestation period and growing period, it can take up to 45 months from start to finish (that’s almost 4 years!) before cattle is available to the market in the form of beef products.” [4]Elliot, Christopher. Queen’s University Belfast. In: Understanding Food Supply Chains. Module 2, Step 2.18. July 2020. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-supply-chains

If there is a sudden surge in demand in beef, it has to be met by imports. Imports and exports of beef are vital to helping the beef sector smooth out ups and downs in demand, and ensuring beef producers have a sustainable business. They also help ensure that consumers have a resilient and reliable supply chain.

As of 2020, the United Kingdom is 75% self-sufficient in beef. It might be counter-intuitive, but it’s important to realize that it’s not necessarily desirable for a country to aim for 100 % self-sufficiency in beef. That would mean farmers having to over-produce at times to meet demand swings, causing them to actually lose money and for their farming businesses to become less viable. Having a portion that is topped up as needed by imports actually improves the resiliency of the supply system, says Dr Christopher Elliot, Director of the Institute for Global Food Safety at Queen’s University Belfast.

He says:

“The UK beef supply chain is estimated to be 75% self-sufficient (National Beef Association, 2020)…. therefore, imports of live beef cattle and of beef products play a vital role in the functioning of the UK beef supply chain to ensure supply meets demand when domestic supply does not match the demand in the marketplace (i.e. imports provide the remaining 25% of domestic demand). It is important to understand that if the UK was to be 100% self-sufficient in beef production, the industry leaves themselves vulnerable to [the many events that impact farming.] For example, if an animal disease outbreak occurred in cattle in the UK our domestic supplies would become unavailable and our supply of the beef products affected would cease. Conversely, if we include imports into our domestic supply of beef products we become more resilient to such shocks.” [5]Ibid., step 1.5

He notes, though, that neither do you want to rely on beef imports to totally meet your country’s need:

“Imports can close a temporary void in the short term but generally can’t be sustained in the medium to long term, as countries in which produce is imported from have their own commitments to domestic and other international customers.” [6]Ibid., Step 2.18

Beef import / export chains also helps beef producers to sell beef products made of beef cuts or discards (for instance, tripe) that may not have a very large market in their own country. As well, note that often as part of export deals with other countries, it is unrealistic to think that you will get away with not accepting any imports from them in return, and, that for business efficiency, import / export chains and distributors are often intertwined.

The beef supply chain does plan for two demand surges each year, the start of barbeque season, and Christmas:

“Generally, demand for beef is relatively steady throughout the year but there are two notable time points in the year that demand for beef will peak among consumers; mainly Christmas and the start of the summer months.” [7]Ibid., Step 2.18

In England, a sudden change in a summer weekend forecast from cold and rainy to hot and sunny can lead to frantic runs on certain types of beef products, such as burgers, but those supply blips will be temporary.

Beef cut terminology is confusing

Beef terminology can be confusing. It can differ from area to area, from store to store, from butcher to butcher, from country to country.

Over the decades, butchers have had a marked tendency to rename beef cuts in an attempt to refresh consumers’ interest. That tendency grew more marked during the 1970s in Canada, US and the UK, when under the failed Wage and Price Control policies in all three countries butchers simply renamed cuts to escape the price controls attached to the more well-known names. And since then, the marketers have taken over and gone into full flight.

Thing is, it all became jargon that only people in the trade understood. Many consumers were left behind, confused, intimated and embarrassed that they didn’t understand something as basic as cuts of beef. But those were the good old days, when producers and retailers had so many beef buyers they didn’t really notice the ones who were confused. Sales were still good enough, with people who did buy sticking to the two or three cuts they knew and understood, and if sales slumped, well, there was always the good old taxpayer to bail them out.

The good old days turned sour in the last decade of the 20th century. A vague “red meat is bad for you feeling” permeated all the health news. People got sick from hamburger and died. The chicken farmers took advantage of this and promoted white meat at a time when white wine was all the rage. The beef market fought back, and recovered a little, but they still didn’t “twig” that when potential buyers came to the beef counter, they stood there confused. Then along came foot and mouth diseases, and then the biggest of all, mad cow. Consumers deserted the beef counter in droves, sales plummeted, and with the worst timing of all, taxpayers started grumbling about bail-outs to any businesses, including agricultural ones.

Beef producers and retailers needed consumers back at the beef counter, but in the meantime they had been buying chicken and fish, and as bonus, these forms of protein were far easier to buy! The clear, standard terminology made it easier to know what to do with them. That made them more convenient for everyday meals.

Something had to be done about the confusion at the meat counter. Canada was one of the first off the mark, where the renaming is already underway. A Rib Roast has become a Rib Oven Roast; a Top Round Roast has become an Inside Round Pot Roast. The goal of the renaming is to be descriptive about where the cut comes from (and no cuts actually come from places on the cow named New York, Kansas City or Delmonico’s) and to let consumers know what to do with their purchase. The packaging also has suggested cooking directions stuck on it. Beef purchases have gone up by 14% in stores that have switched to the new nomenclature over stores that haven’t. Consumers have even begun buying cuts that they previously weren’t familiar with. Sales of pot roasts went up by 190% when people knew what to do with them.

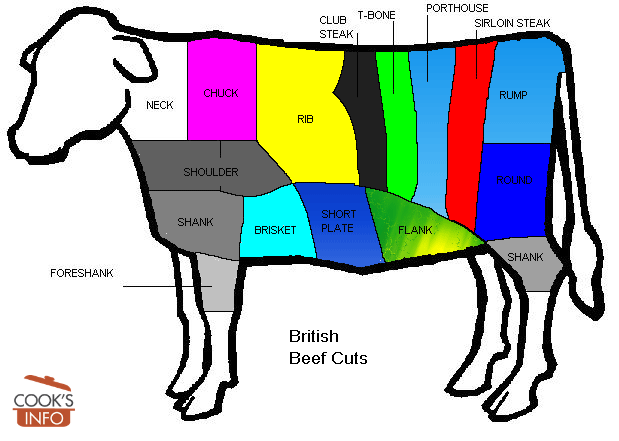

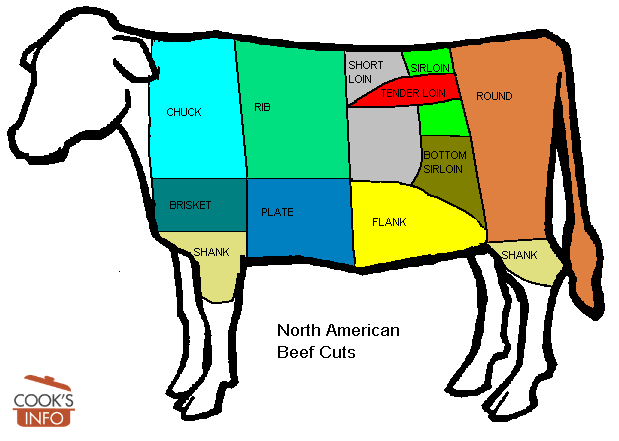

Beef Charts

The main areas shown on beef charts are called primal cuts.

Primal cuts are not sold to consumers; they are sold whole to retailers.

Note that North American terminology is very different from that used in Australia, Britain, Ireland, New Zealand, etc. For instance, in North America, “rump” is a very tough cut with almost no marbling done from the primal area called the “Round”, so North American steak fans would wrinkle their noses at something called a “Rump” steak. In Britain, however, the Rump area is a primal area all its own and comes from a completely different area of the cow, taking in what North Americans would call “Sirloin“, “Tenderloin“, “Top Sirloin“, and “Bottom Sirloin“, with none of the round at all, and very good marbling. So, if you are in North America and are using a British recipe calling for a “rump” steak to be lightly grilled, don’t just reach for a North American rump steak or you will be chewing for days.

British beef cuts chart

British Beef Cuts Chart. © CooksInfo / 2005

North American beef cuts chart

North American Beef Cuts Chart. © CooksInfo / 2005

North American beef primal cuts

- Less tender areas: Neck, Shanks, Chuck, Brisket, Flank, Round

- More tender areas: Rib, Short Loin, Sirloin

Choosing Beef

Beef is normally more of a purple colour. It only turns rosy red when it comes into contact with oxygen. Now, turns out, that rosy red colour is the colour that we consumers have come to associate with “safe to eat.” So, retailers oblige us by packaging our fresh beef in plastic wrap which is actually specially selected to let air through to the meat, to keep the surface of the meat that rosy red colour. That’s why home economists have been saying to us not to trust that packaging for freezing: you’re asking for freezer burn.

Should you happen to see beef on which the dates are good, but the meat is a bit more purply, that simply means it’s been packaged with proper plastic wrap, and because of that will probably actually be fresher than the rosy red stuff. When you expose purply colour beef to the air, it should turn red in about 15 minutes. (The purply colour comes from a pigment called myoglobin; when exposed to oxygen, it turns into oxymyoglobin and becomes the red colour.) Vacuum packed meats will remain the purply colour.

A sign of spoiled beef is meat that doesn’t turn red when exposed to air after 15 minutes, smells sour, and feels sticky when you touch it. But never second-guess yourself: if you’re not 101% sure, throw it out.

Internal temperature reference charts for cooking beef

Quick reference for steak internal temperatures

Remove from grill at these temperatures

- Rare: remove at 120 F (49 C); let rest to 125 F (52 C)

- Medium-rare: remove at 125 F (52 C); let rest to 130 F (54 C)

- Medium: remove at 135 F (57 C); let rest to 140 F (60 C)

Remove from grill at desired temperature. Cover lightly with foil (be sure it has not previously touched raw meat, if so wash), and let rest for 5 minutes before serving or cutting. [8]Steak 101. Cook’s Country. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.cookscountry.com/how_tos/10885-steaks-101

Beef cooking and resting temperatures (metric)

| Doneness | Remove from heat source at: | Let rest until: |

|---|---|---|

| Rare | 48–52°C | 55–60°C |

| Medium-rare | 55–59°C | 61–65°C |

| Medium | 60–66°C | 66–70°C |

| Well-done | 67–71°C | 71–75°C |

Beef cooking and resting temperatures (U.S.)

| Doneness | Remove from heat source at: | Let rest until: |

|---|---|---|

| Rare | 118–125 °F | 131–140 °F |

| Medium-rare | 131–138 °F | 142–149 °F |

| Medium | 140–151 °F | 151–158 °F |

| Well-done | 152–160 °F | 160–167 °F |

Source for cook to / rest temperatures: Knorr. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.knorr.com/ie/a-world-of-flavour/tips-and-tricks/temperature-guide.html

Storage

If you have slaughtered your own beef, you need to cool the meat quickly. So Easy to Preserve, a food preservation manual from the University of Georgia, says,

“Freshly slaughtered meat carcasses or primal cuts need to be cooled to below 40°F within 24 hours to prevent souring or spoiling. The meat should be chilled at 0 to 2 C (32° to 36°F). Variety meats (liver, heart or sweetbreads) are ready to be wrapped and frozen after they are cold. After 24 hours, pork, veal and lamb are ready to be cut, wrapped and frozen. Beef may be left at the 0 to 2 C (32° to 36°F) temperature for a total of 5 to 7 days to age the meat, making it more tender and flavorful.” [9]Andress, Elizabeth L. and Judy A. Harrison. So Easy to Preserve. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Bulletin 989. Sixth Edition. 2014. Page 293.

Store-bought beef can be refrigerated right in its store packaging. Use within 3 to 4 days, otherwise freeze.

Freezing beef

Beef freezes well. University of Nebraska researchers said they did not detect any taste or texture difference between fresh and previously-frozen beef:

“Beef ribeye rolls, strip loins, and top sirloin butts were aged for 14 days and then blast or conventionally frozen and slow or fast thawed, or were fresh, never frozen and aged for 14 days or 21 days. Thawing method affected purge loss and tenderness, and freezing method had a minimal effect. Neither freezing nor thawing methods had an effect on sensory tenderness, and minimal effects on the other sensory attributes. It is possible to freeze and thaw beef subprimals and for the meat to be comparable in tenderness and sensory attributes to fresh, never frozen meat.” [10]Hergenreder, Jerilyn E., et al. Effects of Freezing and Thawing Rates on Tenderness and Sensory Quality of Beef Subprimals. University of Nebraska. 2012 Nebraska Beef Cattle Report. Page 127.

For best quality, use frozen beef within six to twelve months. [11]Freezing meats and seafood. Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service. Factsheet HGIC 3064. Updated 20 June 2012.

Longer storage times in the freezer may affect quality, but it won’t affect safety: it will be safe indefinitely as long as it is kept consistently frozen.

Wrapping beef for freezing

You might be able to put store or commercially-packaged beef in the freezer as is: it depends on the exact packaging. So Easy to Preserve says, “Store-bought meats need to be over-wrapped, since their clear packaging is not moisture-vapor resistant. If you purchase film-wrapped meats from a meat packer, check to see if the wrap is a new heavy-duty film [Ed: or Cryovaced]. If so, it needs no over-wrapping.” [12]So Easy to Preserve. Page 293.

If you intend to use store-packaged beef within two weeks, you could just toss it in the freezer in the store packaging. Otherwise, you may need to consider proper packaging unless it’s the kind of higher-quality packaging mentioned above. That being said, this probably should not be encouraged because how many people really get around to using it within two weeks – out of sight, out of mind.

So Easy to Preserve continues with packaging advice:

“Package the meat in freezer paper or wrap, using either the drugstore or butcher wrap [Ed: these are styles of how to fold freezer paper.] Freezer bags or containers can be used for ground beef, stew beef or other meats frozen in small portions. Package the meat in meal-size portions, removing as many bones as possible (they take up freezer space). Place two layers of freezer paper or wrap between slices or patties of meat so they are easier to separate when frozen. This will help speed thawing.” [13]So Easy to Preserve. Page 293.

Note that freezing does not affect the nutritional value of beef:

“Freezing does not destroy nutrients. In meat and poultry products, there is little change in nutrient value during freezer storage.” [14]Freezing meats and seafood. Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service. Factsheet HGIC 3064. Updated 20 June 2012.

That being said, please note as well that many pathogens survive freezer temperatures, so even though beef may have been frozen, it still requires proper cooking after thawing.

History Notes

Until the 1700s, the same cattle that were used to pull ploughs were also used as beef cattle. These cows were small and their meat was tougher, and there was less meat on them as they were bred for muscle and bone to give them strength for working.

A man from Leicestershire, England, Robert Blakewell, was amongst the first to work on improving breeds of cattle for beef production alone.

Literature & Lore

“Methinks sometimes I have no more wit than a Christian or an ordinary man has: but I am a great eater of beef and I believe that does harm to my wit.” — Sir Andrew in Twelfth Night, Act I, Scene 3. Shakespeare (26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616).

“Give them great meals of beef and iron and steel, they will eat like wolves and fight like devils.” — William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616. Henry V, Act III, Scene 7.)

Sources

Jordan, Harry. Meat Harry. Renfrew, Ontario, Canada: General Store Publishing House. 2003.

Related entries

References

| ↑1 | Hesser, Amanda. Recipe Redux: Rib Roast of Beef, 1966. New York Times. 26 January 2011. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Last year, Oliver backed the launch of Taste The Difference 21-day aged beef, which was one of the most popular products launched by Sainsbury’s in 2003 and now accounts for nearly 10% of beef sales.” Whitehead, Jennifer. Jamie Oliver signs for another year with Sainsbury’s. Campaign Live. London: Haymarket Media Group Ltd. 10 May 2004. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/jamie-oliver-signs-year-sainsburys/210453 |

| ↑3 | Parker Bowles, Tom. Holy cow! How to choose the perfect steak. London: Daily Mail. 14 September 2009. |

| ↑4 | Elliot, Christopher. Queen’s University Belfast. In: Understanding Food Supply Chains. Module 2, Step 2.18. July 2020. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-supply-chains |

| ↑5 | Ibid., step 1.5 |

| ↑6 | Ibid., Step 2.18 |

| ↑7 | Ibid., Step 2.18 |

| ↑8 | Steak 101. Cook’s Country. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.cookscountry.com/how_tos/10885-steaks-101 |

| ↑9 | Andress, Elizabeth L. and Judy A. Harrison. So Easy to Preserve. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Bulletin 989. Sixth Edition. 2014. Page 293. |

| ↑10 | Hergenreder, Jerilyn E., et al. Effects of Freezing and Thawing Rates on Tenderness and Sensory Quality of Beef Subprimals. University of Nebraska. 2012 Nebraska Beef Cattle Report. Page 127. |

| ↑11 | Freezing meats and seafood. Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service. Factsheet HGIC 3064. Updated 20 June 2012. |

| ↑12 | So Easy to Preserve. Page 293. |

| ↑13 | So Easy to Preserve. Page 293. |

| ↑14 | Freezing meats and seafood. Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service. Factsheet HGIC 3064. Updated 20 June 2012. |