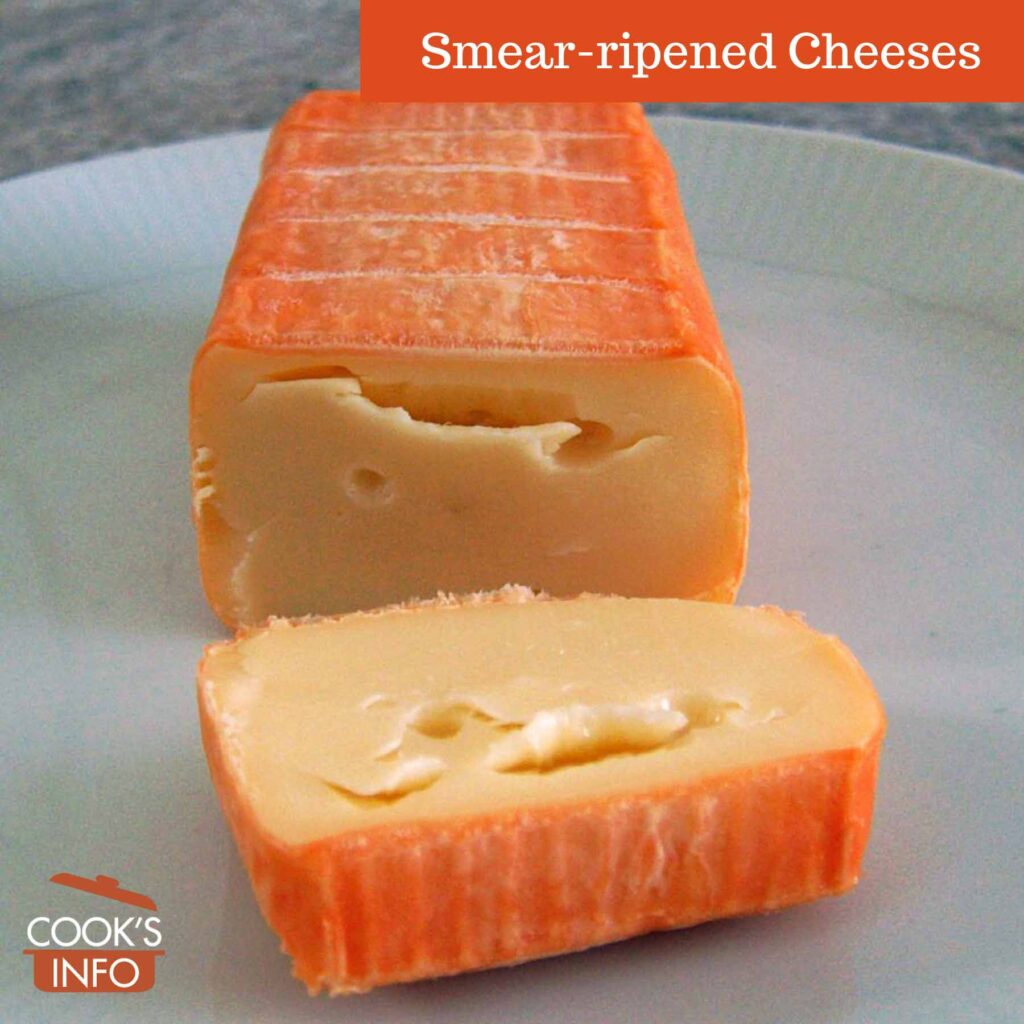

Smear-Ripened Cheeses. Markus Hagenlocher / wikimedia / 2006 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Smear-ripened cheeses are cheeses on whose surfaces bacteria such as “Brevibacterium linens” are encouraged to grow during ripening in order to influence both the flavour and texture of the cheese inside.

These cheeses tend to be somewhat “whiffy”, though the smell is for the most part confined to the rind:

“The strong smell of many bacterial surface-ripened or ‘surface smear’ cheeses is in fact more or less confined to the surface; the inside is usually quite mild in aroma and flavour.” — Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 2014. P. 165. Kindle Edition.

The term smear is used for two reasons: one, is that as the cheese in question ripens, smear-like marks on the surface may become apparent. And secondly, is that typically the bacteria is initially smeared (though more accurately washed or brushed) on to start the process.

This term is often confused with washed-rind cheeses; with washed-rind cheeses, however, the goal is to limit all bacterial growth and encourage mould growth instead.

Smear-ripened cheeses are often, though not always, softer cheeses. Port du Salut style Trappist cheeses are smear-ripened, as is Muenster.

Application of the bacteria

Traditionally, the cheeses are wiped with a brine that has been inoculated with surface samplings from already mature cheeses in order to transmit the desired bacteria. In fact, a richer though not yet thoroughly understand collection of microbiota, including yeasts, is transferred. (In The Oxford Companion to Food, Alan Davidson refers to a “catholic mixture of bacteria, yeasts, and to a small extent moulds.” [1]Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 2014. P. 165. Kindle Edition. )

The yeasts help to raise the pH of the surface of the cheese above 6.00, which bacteria such as B. linens like: [2]W. Bockelmann. The production of smear cheeses In: Dairy Processing, 2003. 21.2.1 Traditional ripening.

“The early surface microbiota of washed-rind cheeses is primarily composed of yeasts that release growth factors and alkalinize the cheese surface by metabolizing the lactate produced by lactic acid bacteria added as starter cultures (Alper et al., 2013). These processes promote the growth of acid-sensitive, salt-tolerant bacterial strains.” [3]Leversque, Sebastien. Mobilome of Brevibacterium aurantiacum Sheds Light on Its Genetic Diversity and Its Adaptation to Smear-Ripened Cheeses. Microbiol., 10 June 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01270

The cheeses would then be washed periodically with brine. This increases the salinity of the surface, and discourages the growth of other moulds and bacteria. It also controls the growth pace of the desired bacteria: “Surface bacteria tend to grow too fast, and are kept in check by frequently washing or brushing.” [4]Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 2014. P. 165. Kindle Edition.

Soumaintrain cheese is washed with a mixture of brine and marc to impart a special flavour to the interior of the cheese.

Some cheeses, such as Milleens Cheese, allow the B. Linens bacteria to find its way to the rind via the air.

The rinds on the resultant cheeses are sometimes edible, sometimes not.

Risk factors

Though the surface environment achieved is high salt and high pH, it is not hostile to pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes which can tolerate such conditions.

A known vulnerability of this smear process is that if the previous batch used to inoculate the new batch had food safety issues, those could be transmitted and ruin the new batch, resulting in both health and economic risks. [5]T.M. Cogan. Control of Listeria in Smear-Ripened Cheeses. In: Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition), 2014.

“[The] disadvantage of this approach is that, if present, undesirable contaminants like the pathogenic Listeria monocytogenes will be spread to all cheeses via the smear machines. Therefore, ripening hygiene of these cheese varieties is widely criticized.” — Definition and characterisation of starter cultures for surface ripening of smear cheeses. EU: Cordis. June 1999. Accessed May 2022 at https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/FAIR984220

History

Smear-ripened cheeses were traditionally made in lowland areas, close to where the markets were, so they didn’t need particularly long storage lives. Thus, many of them were made as softer cheeses. [6]As opposed to cheeses made in highlands and in the mountains. These cheeses often had to be able to last through the winter until passageways down to the markets in the lowlands were safely passable again. This necessity dictated a lower-water content in the cheeses, and thus harder cheeses.

Literature

“The bacterium that gives Münster, Epoisses, Limburger, and other strong cheeses their pronounced stink, and contributes more subtly to the flavor of many other cheeses, is Brevibacterium linens. As a group, the brevibacteria appear to be natives of two salty environments: the seashore and human skin. Brevibacteria grow at salt concentrations that inhibit most other microbes, up to 15% (seawater is just 3%). Unlike the starter species, the brevibacteria don’t tolerate acid and need oxygen, and grow only on the cheese surface, not inside. The cheesemaker encourages them by wiping the cheese periodically with brine, which causes a characteristic sticky, orange-red “smear” of brevibacteria to develop. (The color comes from a carotene-related pigment; exposure to light usually intensifies the color.) They contribute a more subtle complexity to cheeses that are wiped for only part of the ripening (Gruyère) or are ripened in humid conditions (Camembert). Smear cheeses are so reminiscent of cloistered human skin because both B. linens and its human cousin, B. epidermidis, are very active at breaking down protein into molecules with fishy, sweaty, and garlicky aromas (amines, isovaleric acid, sulfur compounds). These small molecules can diffuse into the cheese and affect both flavor and texture deep inside.” — McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (pp. 58-59). Scribner. 2004. Kindle Edition.

Other cheese-related technical terms

- Affinage

- Casein

- Cooked-Curd Cheeses

- Creamery

- Double-Cream Cheese

- Fat Content of Cheeses

- Longhorn Cheese

- Pate (of a Cheese)

- Pressed-Curd Cheeses

- Raw Curd Cheeses

- Rennet

- Semi-Cooked Curd Cheeses

- Skim-Milk Cheeses

- Stretched Curd Cheeses

- Sweet Curd Cheeses

- Triple-Cream Cheese

- Truckle

- Turophile

- Washed-Curd Cheeses

References

| ↑1 | Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 2014. P. 165. Kindle Edition. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | W. Bockelmann. The production of smear cheeses In: Dairy Processing, 2003. 21.2.1 Traditional ripening. |

| ↑3 | Leversque, Sebastien. Mobilome of Brevibacterium aurantiacum Sheds Light on Its Genetic Diversity and Its Adaptation to Smear-Ripened Cheeses. Microbiol., 10 June 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01270 |

| ↑4 | Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 2014. P. 165. Kindle Edition. |

| ↑5 | T.M. Cogan. Control of Listeria in Smear-Ripened Cheeses. In: Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition), 2014. |

| ↑6 | As opposed to cheeses made in highlands and in the mountains. These cheeses often had to be able to last through the winter until passageways down to the markets in the lowlands were safely passable again. This necessity dictated a lower-water content in the cheeses, and thus harder cheeses. |