Christmas pudding. James Petts / flickr / 2015 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Christmas Pudding is a steamed pudding of some type that is served at Christmas with a sweet sauce or thick cream to accompany it.

See also: British Food, Plum Pudding, Christmas Day

- 1 What makes a pudding a Christmas Pudding

- 2 Aging a Christmas pudding

- 3 Prizes in Christmas puddings

- 4 Homemade vs bought Christmas puddings

- 5 Non-alcoholic Christmas puddings

- 6 Reheating Christmas puddings

- 7 Serving Christmas pudding

- 8 Cooking Tips

- 9 History Notes

- 10 Literature & Lore

- 11 Recipes

- 12 Sources

- 13 Videos

What makes a pudding a Christmas Pudding

There is technically no one recipe for what constitutes a Christmas pudding.

There are actually many types of puddings served at Christmas, such as Figgy Pudding or Carrot Pudding. For some people in Canada, particularly those on the West Coast it seems, carrot pudding has become the default Christmas pudding owing to recipes their families adopted during Second World War rationing, and that become their “new” tradition.

And, many people are always in search of lighter puddings to serve after a heavy Christmas meal. But for the vast majority of people, perhaps, Christmas Pudding means ‘plum pudding‘, just as the Christmas bird means turkey. Eliza Acton “is said to be the first to name plum pudding ‘Christmas pudding.'” [1]Clay, Xanthe. Tried and tested: Celebrity chefs’ Christmas pudding recipes. London: The Telegraph. 20 November 2012.”She (Eliza Acton) mentions Christmas pudding for the first time in print – previously it has always been plum pudding.” [2]The First Star Cooks. London, England: The Daily Mail. 18 May 2019.

What’s different about plum pudding served at Christmas, compared to the rest of the year, is that at Christmas it gets tarted up: it may be decorated with a sprig of holly or berries, it may be flamed at the table, and it may contain small prizes to be found by the diners. In a cold, dark time of the year, it’s something sweet and rich on the table that suddenly blazes with blue flames bringing joy and delight to the faces of all.

A Christmas pudding will have lots of fruit in it, like a Christmas fruitcake, but it is always moister and is served warm. Mostly, though, Christmas pudding is about tradition, a tradition in itself, and all the traditions associated with it.

Aging a Christmas pudding

A Christmas pudding needs time to age, like a good fruitcake. Some people make their Christmas pudding a year in advance, but generally they are made on the fifth Sunday before Christmas, giving them about five weeks to age.

In fact, tradition starts with this timing. That Sunday, the fifth before Christmas, which is also the Sunday before Advent or the 25th Sunday after Trinity, has in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer the following collect: “Stir up we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people…” (Collect for Sunday Next Before Advent, Book of Common Prayer.) With that reading in the morning and the making of the pudding in the afternoon, is it any wonder that this day has become fondly known as “Stir-up Sunday“? It is considered good luck for everyone in the house to have a go at stirring it and make a wish while doing so. Tradition further holds that you have to stir clockwise for good luck.

Let a traditional plum pudding meant for Christmas age in a cool, dark, dry place.

The English food writer Delia Smith advises,

“When a pudding is steamed let it get quite cold, then remove the steam papers and foil and replace them with some fresh ones, again making a string handle for easier manoeuvring. Keep it in a cool place away from the light. Under the bed in an unheated bedroom is an ideal place.” [3]Smith, Delia. Delia Smith’s Christmas. London: BBC Books. 1990. Page 38.

It is safe to store these heavy plum puddings unrefrigerated because they are so dense and have so much sugar that they have low water-activity, preventing moulds and other nasties from growing.

Lighter puddings such as carrot or sponge don’t require that aging, and if made in advance must be kept refrigerated because they have a higher water activity.

“WHEN TO MAKE PUDDINGS: Heavily-fruited puddings are made two to four weeks prior to serving. Carrot puddings and other light-types are made one week before needed.” —Adams, Edith. Christmas Baking. British Columbia: Vancouver Sun.

Older writers noted that making Christmas puddings far in advance let cooks take advantage of cheaper prices for eggs, and dried fruit, before higher winter prices set in:

“Many people make their puddings months before Christmas, and this is a capital plan as then eggs are usually cheaper than later on.” — Housekeeping Notes By The Housewife. Belfast, Antrim, Northern Ireland: The Northern Whig. Wednesday, 4 November 1908. Page 7.

Prizes in Christmas puddings

There is a tradition of putting into the pudding mixture a silver coin that will bring good luck to whoever finds it at the table. For many years, it was a silver threepenny piece (aka thruppence, or thruppenny bit.) If you found a ring in your pudding, it meant that you would be married in the upcoming year. If an unmarried woman found a thimble, it meant she would remain a spinstress all her life.

If you do add anything like coins or charms to the pudding, choose items large enough to be noticed and tell everyone to be looking out for them. This serves two purposes: it will increase the fun, and it counts as a word to the wise, so that Christmas dinner doesn’t close with people choking to death or breaking teeth. (In Scandinavia, a single whole almond is placed in the Christmas porridge as the prize, which may be a safer alternative.)

Homemade vs bought Christmas puddings

As much debate as there is over what kind of pudding and what recipe constitutes the true Christmas pudding, the fiercest debate now is about homemade or bought.

Purchased Christmas puddings are very popular, and every year in November the English press races to evaluate which grocery store chain is offering the best, and the best value. The press delights particularly in finding lower-priced ones which in fact which win blind taste-tests and the highest rates.

The one with the best reviews often quickly sells out from the store shelves. Often there is outrage as the sold-out ones then appear on e-Bay or other Internet sites for sale at highly-inflated prices.

The “bragging rights” about having scored one of that year’s top-rated puddings can be as satisfying, some say, as presenting a homemade one.

This is not a modern debate. A Daily Mirror writer addressed the question in 1905 — and came down on the side of purchasing:

“Christmas puddings become realities next Sunday, the 26th, known as ‘Stir-Up Sunday’, when people in old-fashioned households meet to stir the pudding for luck. Like many another good old custom, this one, largely owning to the changes brought about by flat and hotel life, and the growing difficulty of procuring satisfactory servants, is fast falling into disuetude.

Even the home-made Christmas pudding is threatened, largely owing to the same causes. But if the home-made article be a luxury denied to many, the Britisher declines to be deprived altogether of his treat so redolent of old home joys, and calls in the aid of the manufacturer.

And it cannot be denied, setting aside association and sentiment, that the Christmas puddings now manufactured by the million by firms are not only as good to eat as home-made, but cheaper.

A home-made Christmas pudding costs at least 1s. a pound, while a manufactured one costs, for a single pound, 10d. to 10 ½ d., and much less in proportion as the number of pounds increases.

Plum puddings, made by machinery and untouched by hand from start to finish, are turned out in such quantities that some first begin their manufacture nearly a year in advance. The export trade, which is very large, is now practically over for the year. A prominent firm told the Daily Mirror that their trade in this direction is greatly increasing, and continues throughout the year.

Messrs. Buzzard’s in Oxford-street are famed for their plum puddings, which can be bought from 5s. 6d. upwards, and they sell thousands, though their trade is chiefly confined to Yuletide. St Ivel plum puddings are increasing in popularity, and larger numbers even than last year are being made. The puddings are so popular that they are for sale in London tea-shops.” — Stir-Up Sunday: Decline and Fall of Home-Cooked Christmas Puddings. London, England: The Daily Mirror. Monday, 20 November 1905. Page 5, col. 3.

Non-alcoholic Christmas puddings

It’s easy to assume that the desire for alcohol-free Christmas puddings comes from a more-modern healthful mindset. A 1905 writer, however, presented such a recipe that she in fact dated to a hundred years previous to that, making it from around 1805:

“‘Stir-up Sunday, as our dear domesticated ancestresses (now so regretfully belauded by modern man, Orientals at heart, most of them!) called it — a sorry housewife indeed was she who, when the first words of the ‘stir up’ collect resounded through the church, could not whisper complacently to herself: — ‘The Pudding is in the Pot!” — reminded me that I had never sent you my long-promised recipe for a teetotal plum pudding. It descended to me from a great-grandmother — wise in her generation — who, quite a hundred years ago, came to the conclusion that the gout which soured the tempers of her husband and his cronies owed its origin largely to the ‘enemy which men put into their mouths to steal away their brains’ as that mine of Sagacity, Shakespeare, remarks. Now that temperance is quite fashionable you will be rewarded by trying this recipe; it will make three rich and digestible puddings, and will last for months if only your youngsters give it the chance!

Plum Pudding

2 lbs. each of suet, raisins (stoned), currants, sultanas, bread crumbs and apples.

1 ½ lb. each of flour and brown sugar

2 nutmegs, 1 ½ teaspoonfuls of mixed spice, ½ teaspoonful ground ginger, 2 teaspoonfuls carbonate of soda, and 1 small teaspoonful of salt.

The peel of 2 lemons (very fine), 1 oz. candied peel, 8 eggs, and 1 pint milk.

Mix well, and boil 7 hours the first day, and 3 hours before eating.” — Grass Widow’s Gossip. Bedford, Bedfordshire, England: The Bedfordshire Times and Independent. Friday, 1 December 1905. Page 5, col. 4.

Reheating Christmas puddings

The question of how to heat a Christmas pudding for serving offers a form of milder debate. There’s a strong argument to be made for the traditional method of reheating it in a steamer, which will take a few hours. Proponents of this method say that the slow, moist heating process can give the flavours time to slowly waken again and meld together. Plus, they add, even if you bought the pudding ready-made, steaming it will make you feel as though you’ve actually done something towards preparing it.

The argument in favour of microwave reheating can be a more prosaic one: who has a spare stove burner they can tie up for three hours right when Christmas lunch or dinner is being prepared? However, if you have made your own pudding and put any metal prizes in it, whether coins, charms or rings, you probably should err on the side of safety and steam it.

Christmas pudding with pitcher of cream. James Petts / flickr / 2015 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Serving Christmas pudding

Many people attempt, successfully or otherwise, to flame the Christmas pudding just before serving.

Many people serve Christmas pudding with a hard sauce (such as brandy butter), though it’s not uncommon to find pockets of tradition that hold it should be served with a lemon sauce.

Other common accompaniments include brandy or rum sauce, thick pouring cream, or custard.

Typically, these sauces are now purchased. [4]Christmas Pudding. In: Exploring English Food and Culture. The British Council. Module 4.14. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/exploring-english-food-and-culture/1/steps/1189291

Cooking Tips

Slices of leftover Christmas pudding can be nice lightly fried up in a little bit of butter.

History Notes

Christmas pudding, in the form of plum pudding, initially started out as a pottage served at the start of a meal. It grew richer with the addition of dried fruits in the 1500s and as such was served on high feast days such as All Saint’s Day, Christmas and New Year’s Day. But even moving into the 18th century, it was still served as a first course. [5]Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 222.

In the after-math of World War One, fresh eggs were expensive and scarce even going into 1920. One household columnist writer advised using dried egg in Christmas pudding instead:

“There is a legend in most households that plum puddings should be made by Stir-up Sunday. Those who have not yet made them should do so at once. The fruit this year is exceptionally good and though new-laid eggs are scarce and dear, the dried eggs, which are new-laid eggs minus the shells and the water, answer admirably.” — Clive, Kitty. Leicester, Leicestershire, England: Leicester Evening Mail. Friday, 3 December 1920. Page 3, col. 4.

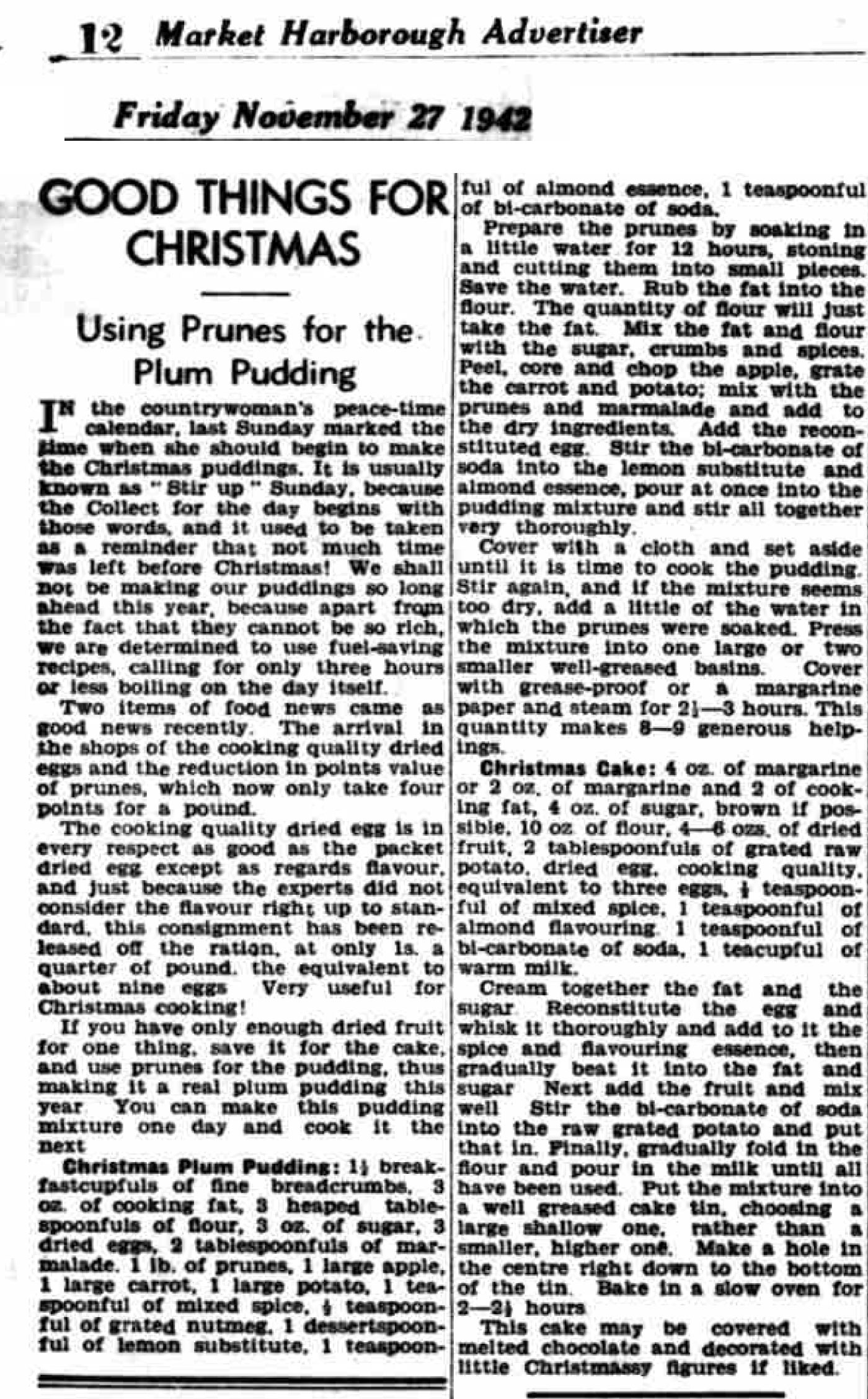

During World War Two, cooks again faced challenges with ingredients for Christmas pudding, and once again, dried eggs were recommended:

1942 wartime Christmas pudding advice. Leicestershire, England: Market Harborough Advertiser and Midland Mail. Friday, 27 November 1942. Page 12, col. 1.

It was well into the 1900s before ovens became common in English homes. Christmas puddings had the advantage over Christmas cake in that they did not require an oven to make, as they were steamed / simmered in a pot instead.

Germans save the English Christmas Pudding

The Puritans banned Christmas pudding in 1664. They felt that it was a “lewd custom”, whose rich, decadent ingredients were “unfit for a God-fearing people.”

Many people are credited with reviving the tradition. One is King George 1st, who was actually German. He had eaten plum pudding earlier in the year of 1714, developed a taste for it, and decided to serve it at his Christmas feast that year, reviving the tradition.

By the start of the 1800s, Christmas pudding was falling out of fashion again, until along came another German to revive it — Prince Albert. That was the only nudge that the Victorians, who loved festive occasions, needed. They were the ones who started putting coins or charms in the Christmas pudding. The tradition of placing things in the pudding is said to be reminiscent of the Roman Saturnalia feast, when cakes were supposedly served with a bean inside them, and whoever found the bean would have luck. [6]CooksInfo is not currently aware of any scholarly let alone primary sources to back this assertion, though food writers have been saying it for a long time. In more recent history, a bean was still placed in a Twelfth Night cake, and it’s perhaps from the Twelfth Night cake tradition that the Victorians got the idea.

Now Christmas pudding, whether remembered fondly or imagined, is firmly a part of an English Christmas.

Christmas Pudding did not make it over to North America

Many North Americans can imagine Christmas pudding as part of a traditional mythical Christmas, but it never actually appears on North American tables. Everything else is there: Christmas crackers, Christmas cake, Christmas trees, egg nog, shortbread cookies, the roasted meat… but how did Christmas pudding get dropped off the list?

Amongst the first Europeans to settle in the United States were the Puritans, the Quakers and other puritanical religious groups. (Canada had the French at that time, who had different religious and food customs altogether.) They came not only to escape religious persecution, but to escape the “sinful excesses” that they had tried and failed to suppress in England, and one of those excesses was Christmas Day. They didn’t celebrate Christmas as a holiday, but kept right on working and ate normal food for dinner that night.

Christmas pudding, though — a steamed, decadent fruit-filled Christmas Pudding — was singled out for a special place on their hate list. It was their bête-noire, with a special place of contempt on their Christmas food list.

Still, some Americans did know of it, even 100 or more years later. Charles Herbert of Newburyport, Massachusetts, a captured American sailor held in Plymouth, England during the American Revolutionary War, in his 1777 prison diary wrote of the efforts of himself and his fellow American prisoners to get themselves a Christmas pudding:

24th December. It is twelve months since I was taken, and as to-morrow is Christmas, and we have a little money, we are resolved to have something more than we had last Christmas; accordingly we sent out for five pounds of flour, one pound of suet, one pound of plums, half a pound of sugar, half an ounce of spice, and two quarts of milk, to mix the same for a pudding.

25th December. Christmas. To-day had our intended pudding, and as there was so much of it that we could not conveniently boil it all in one bag, we made two of it, and the largest was as much as seven of us wanted to eat at one meal, with our other provisions. [7]Charles Herbert. From “A Relic of the Revolution”. Charles H. Peirce, Boston. 1847. Chapter 9.

Still, Christmas pudding, just did not seem to develop firm, broad roots in America.

During the Victorian revival of Christmas traditions in the 1800s, the United States shook off its Puritanical roots and was ready for big Christmas celebrations. It absorbed all the “newer” traditions such as Christmas trees and Christmas cake that were in vogue in the English magazines they read, but the older ones such as Christmas pudding and mummery didn’t quite make the leap from magazine pages to practice (though mummery made it to Newfoundland.)

Some North Americans know vaguely what Christmas pudding is, from mention of it in books or movies, but likely just as many will not. In North America, instead, pie can be a popular dessert at Christmas.

The main barrier is perhaps that North Americans simply don’t know what steamed puddings are, let alone how to make them.

Christmas pudding alight. Matito / flickr / 2006 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Literature & Lore

Charles Dickens records the serving of a Christmas pudding in his 1843 book, “A Christmas Carol”:

“Mrs. Cratchit left the room alone—too nervous to bear witnesses–to take the pudding up, and bring [the pudding] in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose—a supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered–flushed, but smiling proudly–with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs. Cratchit said that, now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had her doubts about the quantity of flour..” — Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol. [bedight = decked]

Guilano’s fish and chip shop, in Newburn, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, offers its customers the chance to tuck in to some deep fried Christmas pudding. dipped in batter and deep-fried, 50p a slice (BBC News, 2003).

The cost of Christmas puddings

Cooks have long bemoaned the cost of the ingredients for Christmas pudding:

“It was Stir-up Sunday yesterday. That is what our grandparents used to call the 25th Sunday after Trinity. They took the name from the first two words of the Collect for the Day, and it was a pleasant family custom, immediately after the morning church, to gather round and stir the Christmas pudding.

Yesterday I observed the ancient ritual with traditional pomp and ceremony. Into a basin of noble proportions I tipped the following ingredients: — 1 lb. of beef suet, finely chopped, 4 oz. of flour, 1 lb. of raisins, ½ lb. of mixed peel, a grated nutmeg, 1 oz. of mixed spice, 1 oz. of ground cinnamon, ½ pint of milk, 2 wineglassfuls of brandy, 1 lb. of breadcrumbs, 1 lb. of sultanas, ½ lb. of currants, 2 lemons, 4 oz. of shredded almonds, a couple of pinches of salt, and 8 eggs.

I was congratulating myself on the fact that this mixture, sufficient to make a pudding for 20 persons, had cost me in all no more than 3s. 8d. when — I woke up. Old-fashioned cookery books made indigestible reading.” — Daydream. Leeds, Yorkshire, England: The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury. Monday, 24 November 1947. Page 2, col. 6.

Recipes

Delia Smith’s Christmas pudding recipe

Sources

Thring, Oliver. Consider Christmas Pudding. Manchester: The Guardian. 21 December 2010.

Videos

References

| ↑1 | Clay, Xanthe. Tried and tested: Celebrity chefs’ Christmas pudding recipes. London: The Telegraph. 20 November 2012. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The First Star Cooks. London, England: The Daily Mail. 18 May 2019. |

| ↑3 | Smith, Delia. Delia Smith’s Christmas. London: BBC Books. 1990. Page 38. |

| ↑4 | Christmas Pudding. In: Exploring English Food and Culture. The British Council. Module 4.14. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/exploring-english-food-and-culture/1/steps/1189291 |

| ↑5 | Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 222. |

| ↑6 | CooksInfo is not currently aware of any scholarly let alone primary sources to back this assertion, though food writers have been saying it for a long time. |

| ↑7 | Charles Herbert. From “A Relic of the Revolution”. Charles H. Peirce, Boston. 1847. Chapter 9. |