Cheeses. Gabriella Fabbri / freeimages / CC0 1.0

Cheese is a dairy product made from the curdled milk of animals such as cows, sheep, goats and water buffalo.

- 1 Cheesemaking

- 2 The water footprint of cheese

- 3 Non-dairy cheeses

- 4 The role of fat in cheese

- 5 Cheese Food

- 6 Melting cheeses

- 7 Cheeses that hold their shape when heated

- 8 Cooking Tips

- 9 Equivalents

- 10 Storage Hints

- 11 History Notes

- 12 Literature & Lore

- 13 Language Notes

- 14 Some cheese recipes

- 15 Sources

- 16 Types of cheeses

Cheesemaking

When making cheese from unpasteurized (aka raw) milk, the milk is often let stand for several hours first — often overnight. This allows bacteria naturally present in unpasteurized milk to start converting the milk sugars in it (lactose) into lactic acid. With pasteurized milk, the bacteria must be added back in, as the pasteurization process has killed them them off. These bacteria are important for the later flavour of the cheese. (Whenever pasteurized milk acidifies on its own, it can be dangerous to consider using it for any consumption purposes, as the bacteria that have entered the milk to do that will be unknown.)

The milk is then curdled, through the addition of rennet or an acid such as vinegar, lemon juice, etc. Acid curdling is usually used for fresh, loose-pack cheeses that won’t be aged, such as cottage cheese or ricotta.

Most cheeses are naturally white, so colour is often added. As well, mould spores might be added at this stage in some cheeses.

The more whey that is pressed out of the curds, the firmer the cheese’s texture and the longer its storage life.

The first step in getting whey out of curds is the addition of salt. Salt expels whey, as well as inhibiting the growth of anything that could spoil the cheese. The salt also encourages a protective rind to form on the cheeses when they are shaped or moulded. The heavier the salting, the heavier the rind that forms.

Next, the curds can be slightly heated or “cooked”, to encourage them to release more whey. This step can also give the curds a slight rubbery texture. To get a more rubbery textured cheese such as gruyère, the curds are cooked more. In making cheese, the temperature ranges between 34 C (95 F) and 39 C (102 F) can be especially critical: 34 C will give a very soft curd cheese, 39 C will yield a very firm cheese, and each degree in between is practically a separate firmness of cheese along the way.

Next, to make a very firm cheese, such as cheddar, the curds are also “milled” or “cheddared”: that is, cut into very small pieces to provide lots of surface for whey to escape.

Finally, there is an opportunity to expel more whey as the cheese is moulded by how hard you press. And, if you put the newly moulded cheese through a press, to extract yet more whey, you get a very dry cheese such as Cheshire. For softer cheeses, such as blue cheeses, you want to leave some whey content in.

During aging, the casein protein in milk breaks down into peptides, which break down into amino acids, which break down into amines. At each stage of breakdown, the flavour gets more complex.

Many cheeses have their rinds washed while aging with brine, wine, wax or oils to prevent the cheese from drying out and moulds from forming on the rind, and to enhance the flavour. They are usually washed with brine (salt-water), but sometimes with wine or other liquids. See separate entry on Washed-Rind Cheeses.

Some cheeses are wrapped in cloth, in which case they are often not touched during their aging process.

The water footprint of cheese

It requires approximately 4,000 litres of water to produce a kilogram of cheese. [1]Hoekstra, A. Y. (2008). The water footprint of food. In J. Förare (Ed.), Water for food (pp. -). The Swedisch Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (Formas). http://www.waterfootprint.org/Reports/Hoekstra-2008-WaterfootprintFood.pdf This appears to be a middle-range estimate: you will in fact see estimates ranging from 3,000 to 5,000 litres, no doubt partly varying owing to the different types of cheeses and farming practices that could be used for the calculations.

Non-dairy cheeses

At the start of the 2020s, manufacturers of non-dairy or “vegan” cheeses (for instance, cashew nut “cheese”), began pressing for the right to legally sell their products labelled as “cheese”. This will be an interesting issue to watch. There are several points to consider:

- There is no doubt that it is in the dairy industry’s financial interest to resist evolution of the term “cheese”;

- The meaning of words and terms does evolve over time;

- Including non-dairy (vegan) “cheeses” in the definition have the benefit of including them in needed regulatory nets designed to prevent food-born illness. In 2021, an outbreak of salmonella from vegan cheese was documented. [2]U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Outbreak Investigation of Salmonella: Jule’s Cashew Brie (April 2021). Accessed January 2022 at https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-salmonella-jules-cashew-brie-april-2021;

- History should also be considered at least for context. Battles were fought by our ancestors to get definitions of certain food terms fixed in law in order to protect consumers from being sold fraudulent or adulterated food products, which led not only to consumers being cheated but all too often to food-borne illness. There is a reason that legal definitions were put into place in the first place.

The role of fat in cheese

Fat acts as a softener or lubricant in cheese. Higher fat cheeses will be softer cheeses; harder cheeses will be lower-fat ones. You’ll notice that many of the hard, grating cheeses are made from skim milk which has a great deal of the fat removed. See also: Fat Content of Cheeses, Skim-Milk Cheeses.

Cheese Food

Processed cheese or “cheese food” — such as cheese slices or cheese spreads — are made of cheese incorporated with fats and other additives to help achieve the desired texture, consistency and shelf life. See separate entry on Processed Cheese.

Cheese shop. Gerhard Bögner / Pixabay.com / 2014 / CC0 1.0

Melting cheeses

When you heat cheese past a certain temperature, the proteins in the cheese separate from the fat and water in the cheese, and coagulate. Tough, stringy masses result. Hard, well-ripened cheeses are better for heating because their broken-down proteins have a harder time coagulating; this broken-down protein also makes them more easy to blend into a sauce. Cheshire cheese is considered by many English cooks to be one of the best cheeses for a cheese sauce.

When a cheese melts, it will either be stringy, like mozzarella, or “flowing”, like Cheshire.

Cheeses that are low or high in acidity don’t melt well.

If a cheese has a high acidity (low pH), such as feta, it will be more brittle, meaning it will crumble, and not melt well. [3]Riedl, Sue. Why melting cheese to perfection is a science. Toronto: The Globe and Mail. 25 January 2011.

Cheeses such as cheddar-type cheeses or Swiss-style cheeses are lower in acidity and consequently melt better. These tend to be cheeses made with rennet.

Cheeses that are higher in calcium tend to be stringy and stretchy when they melt. Mozzarella’s stretchiness comes from the kneading it receives while being made.

High fat, and aging help to loosen a cheese’s protein structure, and make it flow when melted.

Cheeses that hold their shape when heated

Paneer and ricotta don’t melt because of the high whey protein content in them, preventing breakdown. Other cheeses that don’t melt include Haloumi, and Panela.

Cooking Tips

If you need curls or shavings of a cheese, such as Parmesan, a vegetable peeler is the ideal tool.

In Swiss fondue, the alcohol in the wine lowers the boiling point to help prevent the cheese from curdling.

For a cheese board, try putting out just one large, impressive, generous-sized hunk of a gorgeous quality cheese, and accompany it with some relish bits or spend the money you save on really getting a wine that complements it.

Equivalents

1 oz. grated cheese = 30 g = 4 tablespoons = ¼ cup

4 oz. cheese = 125 g = 1 cup, grated

Storage Hints

Wrap soft cheeses in waxed paper or greaseproof paper before storing in fridge; don’t leave them in any plastic wrap they came in. Some, though, suggest storing all cheese in a sealable plastic bag in the fridge with a sugar cube in it, saying that the sugar deters mould.

Hard cheeses such as brick, cheddar, American pizza mozzarella, etc., can be frozen, though they are best used for cooking after freezing.

It is much trickier to freeze soft cheeses such as Brie and be left with something you can do anything with after thawing. Fresh cheeses such as cream cheese, cottage cheese & ricotta freeze a little better. If the cream cheese is grainy when you thaw it, whip it smooth. It is best used after thawing for cooking (e.g. casseroles, baked pastas, etc.), rather than served as is on a plate, as even after whipping it smooth the texture won’t be the same as before freezing.

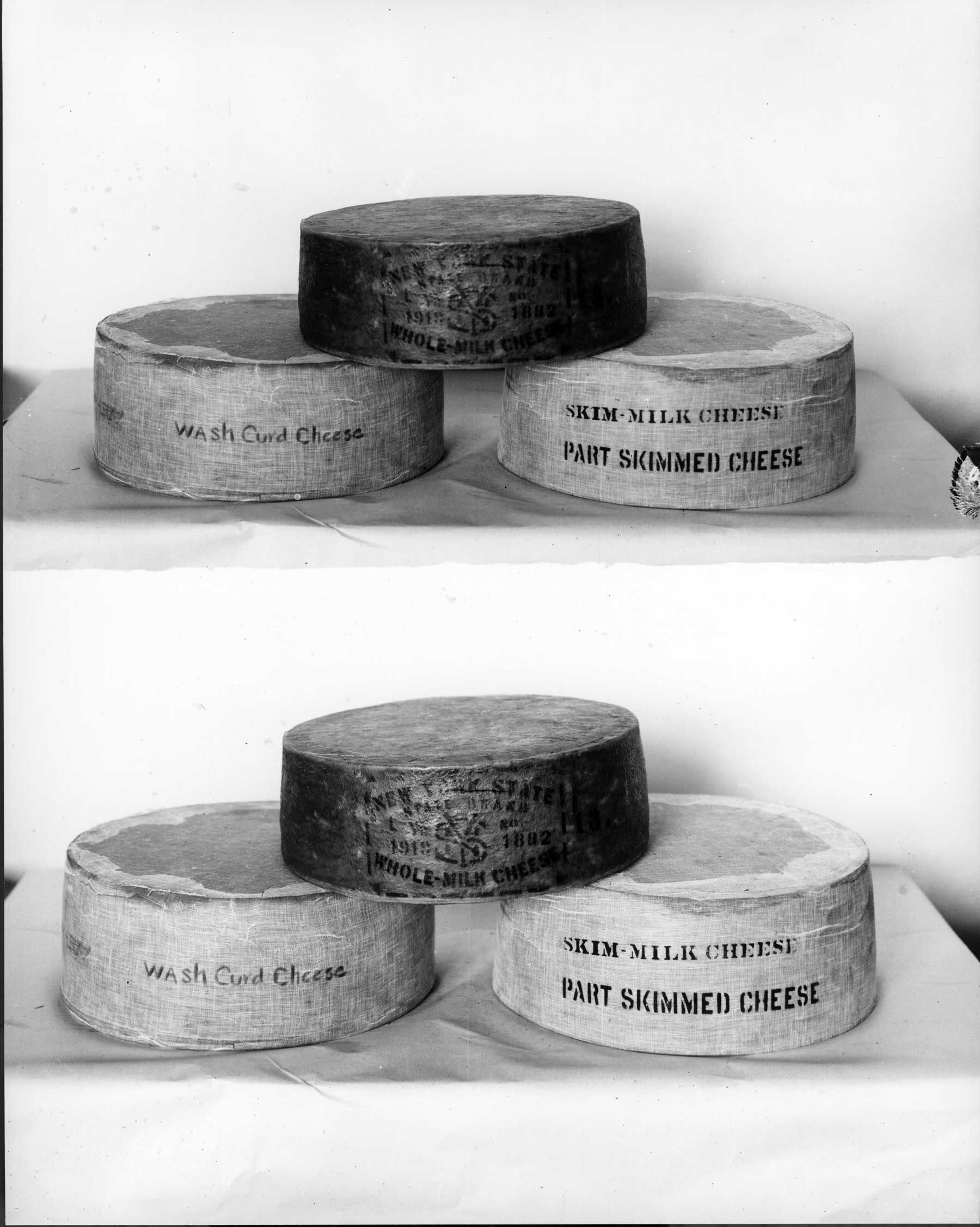

Photo of different kinds of cheeses taken March 19, 1920, by Troy for Miss Cuthbert, and used as the cover illustration for Cornell Reading Course for the Home, Lesson 133 in the Food Series, April 1920, ”Use More Cheese.” Collection #23-2-749, item DD-FN-32. Div. Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

History Notes

The guess is that cheese probably came about through people trying to carry milk in animal skins, which would curdle. From there, the thinking is that the curdled milk in skin bags led to two kinds of dairy products: one for items such as yoghurt and kefir, the other being cheese.

Cheese appears in the Old Testament. In the Middle East, cheese was being made as early as 6000 BC from cow’s and goat’s milk. Egyptians made it.

Ancient Greeks made cheese from sheep and goat’s milk. The Greeks knew about rennet, which improved their cheesemaking and gave them greater control over the process, so that it could start to become a commercial activity. They sold cheese to the Romans.

The Romans learned cheesemaking from others such as the Greeks, and developed it to an art. They brought their cheesemaking know-how to Britain in 55 AD. The Romans didn’t like milk as a beverage: however, they did like cheese, and it is interesting to note that some of their more popular cheeses came from the Roman provinces which are now parts of Switzerland and France.

During the Middle Ages, cheese production from cow’s milk was disrupted, as the lowlands where cow herds had once been kept during the “Pax Romana” became subject to disorder and invasion. Remote mountainous areas were a bit more overlooked by all the chaos, allowing people there to develop cheeses from goat and sheep milk. But no real new cheese varieties appeared during the Middle Ages.

As things settled in the lowlands at the end of the Middle Ages, cow’s milk became available again, and people there had the stability not only to breed cows but also to plan for the future in making cheese. Cheesemaking needs a stable environment for the animals to produce milk, and for the cheese to be manufactured.

Full-cream cheeses were reserved for the rich (in contrast to now, when lower-fat cheeses are flogged to us at a premium.) Skim milk turned out harder, cheaper cheeses that would store and ship well. Using skim milk allowed the cream to be skimmed off to make butter, then cheese could be made from the skim milk.

James VI forbid the export of cheese from Scotland in 1573. In 1661, Charles II put a tax on cheese being exported from Scotland.

In April 2012, the British press reported French presidential chef Bernard Vaussion as saying that cheese had basically been banned from the whole Elysée Palace building by then French President Nicolas Sarkozy. In fact, what Vaussion actually said was that Mr Sarkozy had just chosen not to have a cheese course himself after every dinner. His wife Carla had him on a diet and fitness regime which did, however, include cottage cheese.

Literature & Lore

“Heavens defend me from that Welsh fairy, lest he transform me to a piece of cheese!” — Falstaff. The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act I, Scene I. Shakespeare.

The English comedy show, Monty Python, had a now-famous sketch about cheese in 1972:

Customer: Figures. Predictable, really I suppose. It was an act of purest

optimism to have posed the question in the first place. Tell me:

Owner: Yessir?

Customer:(deliberately) Have you in fact got any cheese here at all.

Owner: Yes, sir.

Customer: Really?

(pause)

Owner: No. Not really, sir.

Language Notes

The Greeks drained some of their cheeses in wicker baskets that they called “formos“. The Romans adopted this word as “forma“. From this came “formaggio“, the standard Italian word for cheese, and “fromage“, the French word.

In Tuscany and some other parts of Italy, cheese is called “cacio” instead of “formaggio“. Cacio comes directly from the other Roman word, “caseus” or “caseum“, for cheese. The English word for cheese came from that Latin word, too, as did the German word “Käse” and the Irish word “cáis“.

In England, hard cheese made from skim milk was called “flet” cheese.

Some cheeses of the world: American Cheeses; British Cheeses; Canadian Cheeses; English Cheeses; Danish Cheeses; French Cheeses; German Cheeses; Greek Cheeses; Irish Cheeses; Italian Cheeses; Mexican Cheeses; Quebecois Cheeses; Scottish Cheeses; Spanish Cheeses; Swiss Cheeses

Some cheese dishes: Cauliflower Cheese, Cheese Balls, Cheesecake, Deep-Fried Cheese Curds, Mattentaart, Moretum, Quesadillas, Welsh Rabbit

Cheese days: Cheese Lovers Day (20th January), Cream Cheese Brownie Day (10th February), Cheese Fondue Day (11th April), Grilled Cheese Day (12th April), Cheeseball Day (17th April), Cheese Day (4th June), Cheesecake Day (30th June), Mac and Cheese Day (14th July), Blue Cheese Dressing Day (16th July), Wine and Cheese Day (25th July), Roquefort Cheese Day (26th July), Cheese Pizza Day (5th September), Cheeseburger Day (18th September), Mouldy Cheese Day (9th October)

Some cheese recipes

- Bacon and Cheese Clafoutis

- Cauliflower Cheese with Bacon

- Cheese and Grape Tortillas

- Cheese Filled Chiles

- Cheese and Tomato Breadcrumb Pie

Sources

Connelly, Andy. Science and magic of cheesemaking. Manchester: The Guardian. 6 January 2010.

Leung, Wency. French President bans fromage? It’s just a cheesy tale. Toronto, Canada: The Globe and Mail. 9 April 2012.

Riedl, Sue. Why melting cheese to perfection is a science. Toronto: The Globe and Mail. 25 January 2011.

Samuel, Henry. France election 2012: Nicolas Sarkozy bans cheese from Elysée Palace. London: Daily Telegraph. 5 April 2012

Types of cheeses

- American Cheeses

- British Cheeses

- Cheese Curds

- Cheese Rinds

- Cheese Technical Terms

- Colby Cheese

- Extra-Hard Cheeses

- Firm (aka Hard) Cheeses

- French Cheeses

- German Cheeses

- Goat’s Milk Cheeses

- Italian Cheeses: Types and Uses

- Mexican Cheeses

- Processed Cheese

- Queso Fundido

- Semi-Firm Cheeses

- Sheep’s Milk Cheeses

- Soft Cheeses

- Surface-Ripened Cheeses

- The Crumblies

- Washed-Rind Cheeses

- Yak Cheeses

- Yeel Cheese

References

| ↑1 | Hoekstra, A. Y. (2008). The water footprint of food. In J. Förare (Ed.), Water for food (pp. -). The Swedisch Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (Formas). http://www.waterfootprint.org/Reports/Hoekstra-2008-WaterfootprintFood.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Outbreak Investigation of Salmonella: Jule’s Cashew Brie (April 2021). Accessed January 2022 at https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-salmonella-jules-cashew-brie-april-2021 |

| ↑3 | Riedl, Sue. Why melting cheese to perfection is a science. Toronto: The Globe and Mail. 25 January 2011. |